48uep6bbphidvals|393

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

The pre-operative tissue diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma is difficult because of its location, small size and desmoplastic reaction. The sensitivity of bile cytology, endobiliary brush cytology and endoscopic transpapillary biopsy varies from 30-86% for detecting malignancy.[1] Patients with preoperative diagnosis of biliary neoplastic lesions are sometimes found postoperatively to have benign disease.[2] Attempt at preoperative tissue diagnosis has found that biliary tuberculosis may mimic cholangiocarcinoma, thus avoiding surgery.[3] Failure to obtain preoperative tissue diagnosis may lead to histological diagnosis of biliary tuberculosis only after major surgery.[4]

We present a case of biliary tuberculosis that was misinterpreted as unresectable cholangiocarcinoma but fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of lymph nodes at porta hepatis confirmed a granulomatous pathology and the management changed from palliation of a malignant lesion to cure of the lesion with anti-tubercular therapy.

Case Report

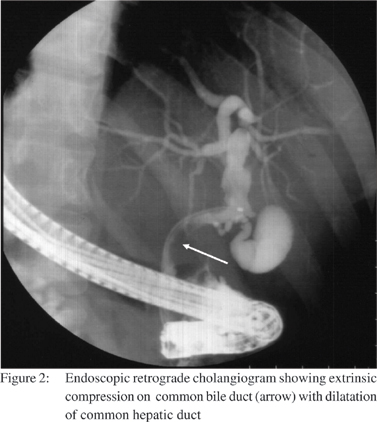

A 25-year-old male presented with high-grade intermittent fever of 2 months duration and progressively increasing cholestatic jaundice for 1 month associated with anorexia and significant loss of weight. Past and family history were not contributory. On examination, he was febrile, deeply icteric and had hepatomegaly with a liver span of 18 cm in the mid-clavicular line. Investigations revealed serum bilirubin of 5.6 mg/dL (direct fraction of 3.5 mg/dL) and serum alkaline phosphatase (SAP) was 31 KAU (normal: up to 12 KAU). SGOT, SGPT, coagulation profile, hemogram and renal functions were normal. HIV serology was normal. Skiagram of the chest was normal. Contrast enhanced CT scan of abdomen showed hypo dense mass lesion at porta hepatic causing biliary obstruction with dilated intrahepatic biliary radicals. There was encasement of the portal vein, superior mesenteric vein, superior mesenteric artery and inferior vena cava. A diagnosis of unresectable cholangiocarcinoma was suggested. CA19-9 was raised 89 U/ mL (normal: <37 U/mL). After selective contrast free cannulation, biliary sphincterotomy was done and a 7French 7cm straight biliary stent was placed to relieve the obstruction. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed 2 columns of small varices, no fundal varices were seen. An ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration cytology from the portal mass revealed a granulomatous lesion. Ziehl Neelsen stain for acid-fast bacilli was negative. Liver biopsy revealed features of extrahepatic biliary obstruction. Anti-tubercular treatment (ATT) in form of isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol was instituted according to body weight. Within 2 weeks the fever spikes decreased. After 6 weeks biliary stent was removed and cholangiogram revealed an extrinsic impression on common bile duct (CBD). After 8 weeks of ATT patient was afebrile, jaundice free, regained his appetite and liver span normalized. Serum bilirubin was 0.8 mg/dL, SAP was 8 KAU, SGOT and SGPT levels were normal. After completion of 6 months of ATT, he is asymptomatic and the lymph nodes compressing the common bile duct has regressed.

Discussion

The present case highlights the importance of pre-operative tissue diagnosis in negating a diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma when mass at porta with raised CA 19-9 and vascular invasion suggested an unresectable cholangiocarcinoma. However, in this young patient with fever before development of jaundice, CA 19-9 levels less than 300 IU/L in presence of cholangitis, a possibility of benign pathology was also considered. FNAC revealed a granulomatous pathology from the lymph nodes at the porta hepatis. In India, where tuberculosis is the most common granulomatous pathology, it was considered the first diagnosis, and there was a good response to ATT.

Biliary tuberculosis is a rare condition that denotes involvement of bile duct causing obstructive jaundice either by enlarged lymph nodes around the bile ducts[5,6,7,8,9] or involvement of biliary epithelium by tuberculous process.[10, 11] The lymph nodes are located at the hepatoduodenal ligament or porta hepatis, that compress the CBD or upper common hepatic duct[5,6,7,8,9] and portal vein[12,13,14] leading to portal hypertension. In the present case, the extrinsic compression from lymph nodes was responsible for biliary obstruction and portal vein compression leading to portal hypertension.

Biliary stricture is not just cholangiocarcinoma. In a surgical series of 98 patients with pre-operative radiological diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma, post operative diagnosis changed after histology in 31% of cases, emphasizing on the importance of tissue diagnosis. The various benign conditions missed were Mirizzi’s syndrome, granulomas (not further clarified) and idiopathic benign focal stenosis.[15] Other benign conditions like tuberculosis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, gastric heterotopia, eosinophilic granuloma, infestations due to Ascaris lumbricoides and Clonorchis sinensis should be thought of.[15]

Although a negative tissue diagnosis will not prevent surgery, causes like tuberculosis can be picked up after tissue diagnosis, as in this case. Hence, tissue diagnosis should be attempted before making a diagnosis of cholangiacarcinoma. CA 19-9 level is raised in benign biliary disease like cholangitis (28%),[16] choledocholithiasis (up to 36%)[17] and Mirizzi’s syndrome.[18,19] In patients of cholangiocarcinoma with cholangitis, the sensitivity is 74% and specificity 41% at cut off level of 37 U/mL, while it is 78% and 83% respectively at 300 U/ml. Hence, for proper interpretation of CA 19-9 one should wait for cholangitis to resolve or consider a cut-off of 300 U/ml in presence of cholangitis.[20] In the present case cholangitis and cholestasis contributed to raised CA 19-9 level.

Hence, biliary tuberculosis is a rare entity that needs high degree of suspicion in young patients with biliary stricture presenting with fever before onset of jaundice. A tissue diagnosis should always be attempted where ever possible because although a negative diagnosis is not helpful, a positive diagnosis may definitely suggest a benign cause, the prognosis of which is definitely better if treated in proper time.

References

1. Patel AH, Harnois DM, Klee GG, LaRusso NF, Gores GJ. The utility of CA 19-9 in the diagnoses of cholangiocarcinoma in patients without primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:204–7.

2. Hadjis NS, Collier NA, Blumgart LH. Malignant masquerade at the hilum of the liver. Br J Surg. 1985;72:659–61.

3. Inal M, Aksungur E, Akgul E, Demirbas O, Oguz M, Erkocak E. Biliary tuberculosis mimicking cholangiocarcinoma: treatment with metallic biliary endoprothesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:1069–71.

4. Behera A, Kochhar R, Dhavan S, Aggarwal S, Singh K. Isolated common bile duct tuberculosis mimicking malignant obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2122–3.

5. Pombo F, Soler R, Arrojo L, Juega J. US and CT findings in biliary obstruction due to tuberculous adenitis in the periportal area. 2 cases. Eur J Radiol. 1989;9:71–3.

6. Alvarez SZ. Hepatobiliary tuberculosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13:833–9.

7. Kohen MD, Altman KA. Jaundice due to a rare cause: tuberculous lymphadenitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1973;59:48–53.

8. Murphy TF, Gray GF. Biliary tract obstruction due to tuberculous adenitis. Am J Med. 1980;68:452–4.

9. Stanley JH, Yantis PL, Marsh WH. Periportal tuberculous adenitis: a rare cause of obstructive jaundice. Gastrointest Radiol. 1984;9:227–9.

10. Fan ST, Ng IO, Choi TK, Lai EC. Tuberculosis of the bile duct: a rare cause of biliary stricture. Am J Gastroenterol. 1989;84:413–4.

11. Bearer EA, Savides TJ, McCutchan JA. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of hepatobiliary tuberculosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:2602–4.

12. Dutta U, Bhutani V, Nagi B, Singh K. Reversible portal hypertension due to tuberculosis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2000;19:136–7.

13. Jazet IM, Perk L, De Roos A, Bolk JH, Arend SM. Obstructive jaundice and hematemesis: two cases with unusual presentations of intra-abdominal tuberculosis. Eur J Intern Med. 2004;15:259–61.

14. Caroli-Bosc FX, Conio M, Maes B, Chevallier P, Hastier P, Delmont JP. Abdominal tuberculosis involving hepatic hilar lymph nodes. A cause of portal vein thrombosis and portal hypertension. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1997;25:541–3.

15. Wetter LA, Ring EJ, Pellegrini CA, Way LW. Differential diagnosis of sclerosing cholangiocarcinomas of the common hepatic duct (Klatskin tumors). Am J Surg. 1991;161:57–62; discussion -3.

16. Ker CG, Chen JS, Lee KT, Sheen PC, Wu CC. Assessment of serum and bile levels of CA19-9 and CA125 in cholangitis and bile duct carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1991;6:505–8.

17. Okaga M, Karasawa H, Kobayashi T, Satsukime N, Miki R. [Effect of biliary tract obstruction and cholangitis on serum CA 19–9 levels]. Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1985;82:1418.

18. Principe A, Del Gaudio M, Grazi GL, Paolucci U, Cavallari A. Mirizzi syndrome with cholecysto-choledocal fistula with a high CA19-9 level mimicking biliary malignancies: a case report. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50:1259–62.

19. Lin CL, Changchien CS, Chen YS. Mirizzi’s syndrome with a high CA19-9 level mimicking cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997;92:2309–10.

20. Kim HJ, Kim MH, Myung SJ, Lim BC, Park ET, Yoo KS, et al. A new strategy for the application of CA19-9 in the differentiation of pancreaticobiliary cancer: analysis using a receiver operating characteristic curve. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:1941–6.