48uep6bbphidvals|432

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

An 80-year-old male presented with worsening fever, chills

and night sweats 10 days after he received his fifth intravesical

BCG instillation for his recurrent low-grade transitional cell

carcinoma of the bladder. Review of systems was remarkable

for mild dysuria and hematuria. Physical examination revealed

a temperature of 102°F. He had no hepatosplenomegaly or

lymphadenopathy. Laboratory evaluation was significant for

leukopenia (3000/µL) and elevated LFTs (alkaline phosphatase

(ALP)-378 U/L, AST-70 U/L, ALT-26 U/L). Prior to presentation,

isoniazid was initiated by his urologist for presumptive BCG

infection. Rifampin and levofloxacin were added upon

admission to the hospital. Routine blood and urine cultures did not yield any pathogens and the results of serologic tests

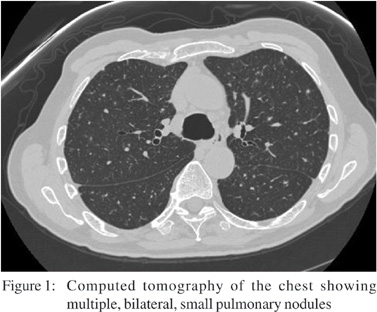

to assess virus, bacteria, and fungus were negative. Chest Xray was unremarkable but the chest-CT revealed diffuse, miliary

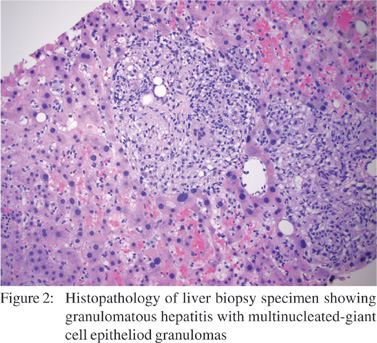

nodular infiltrates suspicious for Mycobacterium infection (Figure 1). A USG-guided liver biopsy was performed for a

persistently elevated ALP and revealed granulomatous hepatitis with non-caseating epithelioid granulomas (Figure

2). Gram stain, AFB, GMS, FITE and immunohistochemical

stains did not detect any organisms and tissue culture was

negative. Worsening pancytopenia prompted a bone marrow

biopsy that revealed multiple large granulomas. The patient gradually improved and his fever subsided within several days of anti-tuberculous therapy. Liver abnormalities resolved during

the following week. He completed a 6-month course of isoniazid

and rifampin, and continues to do well at 1-year follow-up.

Intravesical BCG is an effective treatment for superficial

bladder cancer with a success rate varying between 63 and

100%.[1,2] Minor complications including hematuria, cystitis, fever

(<38.5°C) and malaise are quite common, whereas major

complications such as both local (granulomatous prostatitis,

epididymo-orchitis, ureteral obstruction, bladder contracture)

and systemic reactions (fever >39.5°C, sepsis, pancytopenias,

granulomatous hepatitis and pneumonitis) occur

occasionally.[2,3,4,5]

BCG complications generally result from contiguous and

hematogenous spread of intravesical mycobacteria through

inflamed and/or disrupted urothelium most frequently caused

by traumatic catheterization, bladder perforation, or by

extensive tumor resection.[2,3,4,5] Granulomatous hepatitis is a rare

(<0.4%) and serious complication after BCG instillation, with

unclear pathogenesis.[2,3,4] It has been considered a

hypersensitivity reaction to BCG based on negative staining

and cultures of liver tissue.[2,3,4] However, cases have been

reported in which mycobacteria were present on staining and

mycobacterial DNA was detected in liver tissue suggesting a

liver infection after hematogenous dissemination of BCG, rather

than hypersensitivity.[4]

There have been no prospective studies to evaluate the

optimal treatment for BCG infection.[2,3,4,5] In severe systemic cases,

some data supports the administration of three anti-tuberculous

drugs including isoniazid, rifampin and ethambutol for at least 6 months.[2,3,4] The addition of corticosteroids during initial

therapy may assist in a faster resolution of inflammatory

complications.[2,3,4]

References

- Witjes JA, vd Meijden AP, Debruyne FM. Use of intravesical

bacillus Calmette-Guerin in the treatment of superficial

transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: an overview. Urol

Int. 1990;45:129–36.

- Trevenzoli M, Cattelan AM, Marino F, Sasset L, Donà S,

Meneghetti F. Sepsis and granulomatous hepatitis after

bacillus Calmette-Guerin intravesical installation. J Infect.

2004;48:363–4.

- Lamm DL, van der Meijden PM, Morales A, Brosman SA, Catalona WJ, Herr HW, et al. Incidence and treatment of

complications of bacillus Calmette-Guerin intravesical

therapy in superficial bladder cancer. J Urol.

1992;147:596–600.

- Leebeek FW, Ouwendijk RJ, Kolk AH, Dees A, Meek JC,

Nienhuis JE, et al. Granulomatous hepatitis caused by

Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) infection after BCG bladder

instillation. Gut. 1996;38:616–8.

- Gonzales OY, Musher DM, Brar I, Furgeson S, Boktour MR, Septimus EJ, et al. Spectrum of bacillus Calmette-Guerin

(BCG) infection after intravesical BCG immunotherapy. Clin

Infect Dis. 2003;36:140–8.