48uep6bbphidvals|445

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Congenital absence of the portal vein (CAPV) is a rare anomaly

in which portal venous blood bypasses the liver through a

congenital portosystemic shunt.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] The drainage sites of portal

venous blood include the inferior vena cava (IVC), the left

renal vein and less commonly the internal iliac vein, azygosvein and right atrium.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] Although the portosystemic shunt

may be accompanied by hyperammonemia, hyperbilirubinemia

and hypergalactosemia; hyperinsulinemia and

hyperandrogenism have rarely been reported in patients with

CAPV.[1,12] To the best of our knowledge, only three cases of

congenital extrahepatic portosystemic shunts with

hyperinsulinemia and hyperandrogenism have been

reported.[5,12] We report a case of CAPV associated with large

inferior mesenteric-caval shunt in a 20 year old female with

hyperinsulinemia and hyperandrogenism.

Case report

A 20 year old female presented to our hospital with history of

rectal bleeding since 5 years of age. She required multiple blood

transfusions because of chronic rectal bleeding and severe

anemia. She underwent hemorrhoidectomy thrice in past

without any significant relief in the symptoms. No significant

family history was present. The patient had primary

amenorrhoea and signs of secondary virilization including

clitoromegaly. On examination, breast development was normal

(Tanner stage 4). There were excessive hairs over the face and

back. Neurological examination was normal and there were no

manifestation of hepatic encephalopathy.

Liver function tests revealed normal levels of transaminase,

alkaline phosphate and bilirubin. Serological markers for

hepatitis B and C were negative and serum ammonia levels

were normal (48 µg/dl). Serum FSH, LH and estradiol were within

normal range. Oral glucose tolerance test revealed

hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia indicating insulin

insensitivity. Serum testosterone levels were 1.49 ng/ml (normal

range: 0.05-0.73 ng/ml), and dehydroepiandosterone (DHEA)

level was 6.5 ng/ml.

Ultrasound revealed absence of the portal vein. The right

lobe of the liver was hypoplastic and there was no focal lesion.

However, ultrasound failed to demonstrate the anatomy of extra

hepatic portosystemic shunt. Ultrasound pelvis revealed

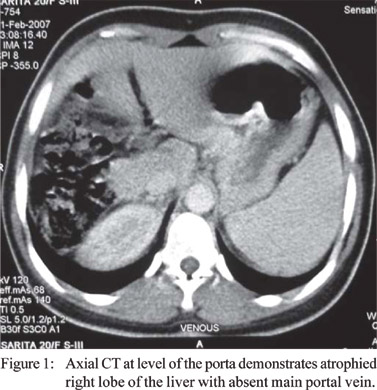

normal sized uterus and enlarged ovaries. CECT of the abdomen

revealed normal hepatic veins and absence of intrahepatic portal

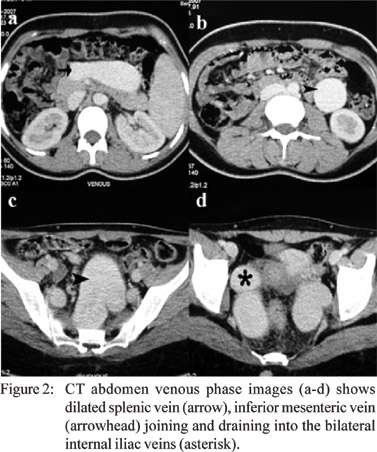

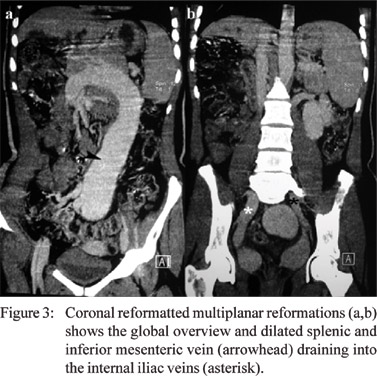

vein (Figure 1). A markedly dilated inferior mesenteric vein

was seen draining into the internal iliac veins (Figure 2, 3).

Celiac axis and superior mesenteric artery were normal. Spleen

was normal in size and there were no portosystemic collaterals.

Echocardiography was normal.

A diagnosis of the congenital absence of the portal vein

associated with large inferior mesenteric-caval shunt causing

hyperinsulinemia and hyperandrogenism was made. The patient

was started on the cyclic oestrogen and her menstrual cycles

started.

Discussion

Congenital absence of the portal vein (CAPV), a subtype of

congenital portosystemic shunt is a rare anomaly with only

few cases reported in the literature.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] Abernethy malformation

in which there is congenital diversion of the blood away from

the liver was first reported in 1793. Morgan and Superina[13]

classified congenital extra hepatic portosystemic shunts in two

types: type 1 (side to end anastomosis) or congenital absence

of the portal vein occurs predominately in females and is

associated with multiple malformations; and Type II (side to

side anastomosis) in which portal vein supply is partially

preserved and have no sex predisposition and associated

malformations.

In CAPV the intestinal and splenic venous drainage

bypasses the liver and drains directly into the systemic veins.[13]

CAPV is further classified into two types based on the anatomy

of the portal vein. In type A, the superior mesenteric vein and

splenic vein do not join and drain separately into systemic

veins. In type B, the superior mesenteric vein and the splenic

vein join before draining into systemic vein. Drainage sites

include inferior vena cava (IVC), the left renal vein and less

commonly the internal iliac vein, azygos vein and right atrium.

The present case corresponds to type B.

CAPV with large inferior mesenteric–iliac vein shunt is

uncommon since shorter tracts (splenorenal, superior

mesenteric-caval) are utilized in preference to this long venous

channel. CAPV results from aberration in venous development in

early embryonic life. Embryologically, portal vein develops from

selective involution of right and left vitelline veins and their

medial anastomosis during second month of gestation.

Excessive involution results in absence of the portal vein.

Development of inferior vena cava in close proximity of the

portal vein and during same time period likely explains the

basis of congenital extra hepatic portosystemic shunts.[3,6]

The age of diagnosis of CAPV ranges from 1 day to 64

years. However, they predominantly occur in females and

children.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] Extrahepatic portosystemic shunt occurs without

secondary signs of portal hypertension, such as venous

collateral, ascites, and splenomegaly. Liver function tests and

ammonia levels are either normal or mildly elevated. Clinical

presentation is variable and reported presentations include

hypergalactosemia, hyperammonemia, hyperbilirubinemia, liver

mass, mental retardation, amenorrhea and hemorrhoidal

bledding.1-12 Our case presented with complaints of

hemorrhoidal bleeding and amenorrhea.

Hyperinsulinemia in congenital portosystemic shunt is

secondary to increased production and reduced clearance of

the insulin. Production increases because of impaired glucose

utilization by liver secondary to reduced supply of insulin and

glucose from portal vein. Portal blood bypasses the liver, thus

reducing the clearance of insulin. Satoh et al[12] postulated that

hyperinsulinemia in congenital portosystemic shunt leads to

hyperandrogenism akin to insulin resistance states like

polycystic ovary syndrome and insulin resistance diabetes

mellitus.

Congenital absence of the portal vein is usually associated

with other congenital abnormalities[1,10,14] including

cardiovascular (dextrocardia, ventricular or atrial septal defects,

patent foramen ovale and ductus arteriosus); skeletal

(hemivertebrae, oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia); and biliary

(biliary atresia). None of these congenital malformations was

present in the present case. Liver neoplasm (focal nodular

hyperplasia, adenoma, hepatoblastoma, HCC) are also

frequently associated with CAPV.[14] No hepatic lesion was

identified in our patient.

The right lobe of liver was hypoplastic in the present case.

Similarly hypoplastic right lobe and small liver volumes was

reported by Goo et al.[8] The authors postulated that hypoplasia

might have resulted from insufficient supply of hepatotrophic

substance to the liver. Liver transplantation is the only effective

treatment for CAPV.

References

- Hu GH, Shen LG, Yang J, Mei JH, Zhu YF. Insight into congenital

absence of the portal vein: is it rare? World J Gastroenterol.

2008;14:5969–79.

- Gallego C, Miralles M, Marin C, Muyor P, Gonzalez G, Garcia-

Hidalgo E. Congenital hepatic shunts. Radiographics.

2004;24:755–72.

- Komatsu S, Nagino M, Hayakawa N, Yamamoto H, Nimura Y.

Congenital absence of portal venous system associated with a

large inferior mesenteric-caval shunt: a case report.

Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:286–90.

- Arana E, Marti-Bonmati L, Martinez V, Hoyos M, Montes H.

Portal vein absence and nodular regenerative hyperplasia of the

liver with giant inferior mesenteric vein. Abdom Imaging.

1997;22:506–8.

- Grazioli L, Alberti D, Olivetti L, Rigamonti W, Codazzi F,

Matricardi L, et al. Congenital absence of portal vein with nodular

regenerative hyperplasia of the liver. Eur Radiol. 2000;10:820–5.

- Niwa T, Aida N, Tachibana K, Shinkai M, Ohhama Y, Fujita K, et

al. Congenital absence of the portal vein: clinical and radiologic

findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26:681–6.

- Turkbey B, Karcaaltincaba M, Demir H, Akcoren Z, Yuce A,

Haliloglu M. Multiple hyperplastic nodules in the liver with

congenital absence of portal vein: MRI findings. Pediatr Radiol.

2006;36:445–8.

- Goo HW. Extrahepatic portosystemic shunt in congenital absence of the portal vein depicted by time-resolved contrast-enhanced MR angiography. Pediatr Radiol. 2007;37:706-9.

- Takagaki K, Kodaira M, Kuriyama S, Isogai Y, Nogaki A, Ichikawa

N, et al. Congenital absence of the portal vein complicating hepatic

tumors. Intern Med. 2004;43:194–8.

- De Gaetano AM, Gui B, Macis G, Manfredi R, Di Stasi C.

Congenital absence of the portal vein associated with focal nodular

hyperplasia in the liver in an adult woman: imaging and review of

the literature. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:455–9.

- Kawano S, Hasegawa S, Urushihara N, Okazaki T, Yoshida A,

Kusafuka J, et al. Hepatoblastoma with congenital absence of the

portal vein - a case report. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2007;17:292–4.

- Satoh M, Yokoya S, Hachiya Y, Hachiya M, Fujisawa T, Hoshino

K, Saji T. Two hyperandrogenic adolescent girls with congenital

portosystemic shunt. Eur J Pediatr. 2001;160:307–11.

- Morgan G, Superina R. Congenital absence of the portal vein:

two cases and a proposed classification system for portasystemic

vascular anomalies. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:1239–41.

- Pichon N, Maisonnette F, Pichon-Lefièvre F, Valleix D, Pillegand

B. Hepatocarcinoma with congenital agenesis of the portal vein.

Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2003;33:314–6.