|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Case Report |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

|

|

Kirtikumar Jagdish Rathod, Zameer Mohd, Ravi Kanojia, Kln Rao

Department of Pediatric Surgery, Advanced Pediatric Center,

Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER)

Chandigarh - 160012, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Kirtikumar Jagdish Rathod

Email: drkirtirathod@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.2012.33

48uep6bbphidvals|518 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Segmental dilatation of small intestine although described in literature, is among the rare causes of intestinal obstruction in neonates. The etiology of this condition remains unknown.[1] Clinical presentation in these patients is like any other intestinal obstruction but investigations often reveal a confusing picture, thereby arousing clinical suspicion of this condition. Once the diagnosis is confirmed resection of the affected segment is the treatment of choice. We present here a case of neonatal intestinal obstruction due to segmental ileal dilatation and discuss the pertinent clinical aspects of this condition with a relevant review of literature.

Case report

We present here a female child born to a primigravida mother at 37 weeks of gestation with birth weight of 2.2 kg. The baby cried immediately after birth and passed meconium on first day of life. Around one week after birth the baby started developing abdominal distension, poor oral intake and bilious vomiting. With these symptoms the child was referred to our institute as a case of neonatal intestinal obstruction. On examination the child’s activity was fair and vitals were stable although the child was dehydrated. Nasogastric tube aspirate was bilious and the abdomen was grossly distended. Bowel sounds were absent. Plain radiograph abdomen revealed a grossly distended small bowel loop on right side of the abdomen, while rest of the small bowel was mildly distended. There was no pneumoperitoneum (Figure 1). Gastrointestinal contrast study revealed a confusing picture with the same persistently distended bowel loop on right side of the abdomen with two separately distended contrast filled bowel loops in the abdomen making us suspect intestinal duplication, although a small quantity of dye was reaching till rectum (Figure 2).

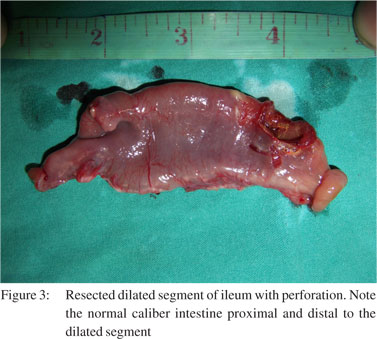

On laparotomy an 8 cm segment of ileum, 10 cm proximal to the ileocecal junction was found dilated. The diameter of dilated segment was 3 cm. There was perforation on the antimesentric side of the dilated bowel. The small bowel proximal and distal to the dilated segment was of normal caliber and texture (Figure 3). The dilated segment of the ileum along with the perforation was resected and an end–to-end anastomosis of the normal bowel was fashioned. The child was discharged uneventfully on eighth postoperative day. The histopathology of the resected specimen showed features of chronic inflammation with normal ganglion cells.

On laparotomy an 8 cm segment of ileum, 10 cm proximal to the ileocecal junction was found dilated. The diameter of dilated segment was 3 cm. There was perforation on the antimesentric side of the dilated bowel. The small bowel proximal and distal to the dilated segment was of normal caliber and texture (Figure 3). The dilated segment of the ileum along with the perforation was resected and an end–to-end anastomosis of the normal bowel was fashioned. The child was discharged uneventfully on eighth postoperative day. The histopathology of the resected specimen showed features of chronic inflammation with normal ganglion cells.

Discussion

Although neonatal intestinal obstruction due segmental intestinal dilatation is described in literature, etiology of this entity remains unknown.[1,2] It often manifests as an isolated, dilated small bowel segment, without evidence of intrinsic or extrinsic obstruction or abnormal neural innervation. In the neonatal period it presents with acute intestinal obstruction or can mimic Hirschsprung’s disease, while in older infants it presents with anemia, malabsorption, chronic constipation or features of intermittent intestinal obstruction.[3] Swenson and Rathauser in 1959 established the criteria for the diagnosis of this rare entity.[4] Their criteria included, (i) limited bowel dilatation with a 3- to 4-fold increase in size, (ii) an abrupt transition between dilated and normal bowel, (iii) no intrinsic or extrinsic barrier distal to the dilatation, (iv) clinical picture of intestinal occlusion or sub-occlusion, (v) a normal neuronal plexus, and (vi) complete recovery after resection of the affected segment.

Around 150 odd cases of segmental intestinal dilatation are reported in literature but none of them provide any clues to the definite etiology of this disease.[5] The presence of hererotopic tissue like lung, pancreatic, esophageal, gastric, cartilage and striated muscle in the dilated segment is described by some authors.[6] Some authors suggest intrauterine vascular accidents or external compression to the fetal bowel as a probable cause of the intestinal dilatation.[7] Entrapment of the bowel, with incomplete intestinal obstruction within the omphalocoele during gestation, has also been postulated as a cause.[8] Cheng et al[9] demonstrated localized vacuolization of the intestinal smooth muscle in their case suggesting myopathy to the cause of dilatation. Partial or complete absence of muscularis propria in the dilated segment has also been reported by some authors but similar findings have not been observed by other authors.[10]

Discussion

Although neonatal intestinal obstruction due segmental intestinal dilatation is described in literature, etiology of this entity remains unknown.[1,2] It often manifests as an isolated, dilated small bowel segment, without evidence of intrinsic or extrinsic obstruction or abnormal neural innervation. In the neonatal period it presents with acute intestinal obstruction or can mimic Hirschsprung’s disease, while in older infants it presents with anemia, malabsorption, chronic constipation or features of intermittent intestinal obstruction.[3] Swenson and Rathauser in 1959 established the criteria for the diagnosis of this rare entity.[4] Their criteria included, (i) limited bowel dilatation with a 3- to 4-fold increase in size, (ii) an abrupt transition between dilated and normal bowel, (iii) no intrinsic or extrinsic barrier distal to the dilatation, (iv) clinical picture of intestinal occlusion or sub-occlusion, (v) a normal neuronal plexus, and (vi) complete recovery after resection of the affected segment.

Around 150 odd cases of segmental intestinal dilatation are reported in literature but none of them provide any clues to the definite etiology of this disease.[5] The presence of hererotopic tissue like lung, pancreatic, esophageal, gastric, cartilage and striated muscle in the dilated segment is described by some authors.[6] Some authors suggest intrauterine vascular accidents or external compression to the fetal bowel as a probable cause of the intestinal dilatation.[7] Entrapment of the bowel, with incomplete intestinal obstruction within the omphalocoele during gestation, has also been postulated as a cause.[8] Cheng et al[9] demonstrated localized vacuolization of the intestinal smooth muscle in their case suggesting myopathy to the cause of dilatation. Partial or complete absence of muscularis propria in the dilated segment has also been reported by some authors but similar findings have not been observed by other authors.[10]

Although segmental dilatation can involve anywhere from duodenum to distal colon, ileum is the most commonly affected site.[11] The usual finding on laparotomy is localized dilation of an isolated, well defined segment of bowel with apparently normal bowel proximal and distal to this segment. The obstruction in these cases is a functional and non-mechanical because the lumen of the dilated segment is continuous with rest of the intestine, as was noted in our case. We could easily see the passage of feces and gas across the lumen of dilated segment while milking the bowel. The microscopic examination of the dilated segment also shows normal histology with normal innervations and normal distribution of ganglion cells.[7] The features of inflammation seen in our case were probably due to perforation of the dilated segment. Although resection of the dilated segment and end-to-end anastomosis of the normal bowel is the definitive curative treatment, the cause of this condition remains unexplained. The diagnosis of segmental intestinal dilatation should be kept in mind while dealing with cases of neonatal intestinal obstruction. As the etiopathogeneis of the entity is still obscure, the resected dilated portion of the intestine should always be sent to appropriate experienced centers for a thorough histopathological and biochemical evaluation.

References

- Balik E, Taneli C, Yazici M, Demircan M, Herek O. Segmental dilatation of intestine: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1993;3:118–20.

- Ben Brahim M, Belghith M, Mekki M, Jouini R, Sahnoun L, Maazoun K, et al. Segmental dilatation of the intestine. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1130–3.

- Manikoth P, Paul J, Zachariah N, Vaishnav A, Sajwani MJ. Congenital segmental dilatation of the small bowel. J Pediatr. 2004;145:415.

- Swenson O, Rathauser F. Segmental dilatation of the colon: a new entity. Am J Surg. 1959;97:734–8.

- Ben Brahim M, Belghith M, Mekki M, Jouini R, Sahnoun L, Maazoun K, et al. Segmental dilatation of the intestine. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:1130–3.

- Rovira J, Morales L, Parri FJ, Juliá V, Claret I. Segmental dilatation of the duodenum. J Pediatr Surg. 1989;24:1155–7.

- Ratan SK, Kulshrestha R, Ratan J. Cystic duplication of the cecum with segmental dilatation of the ileum: report of a case. Surg Today. 2001;31:72–5.

- Thambidorai CR, Arief H, Noor Afidah MS. Ileal perforation in segmental intestinal dilatation associated with omphalocoele. Singapore Med J. 2009;50:e412–4.

- Cheng W, Lui VCH, Chen QM, Tam PK. Enteric Nervous System, interstitial Cells of Cajal, and smooth muscle vacuolization in segmental dilatation of jejunum. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:930–5.

- Huang SF, Vacanti J, Kozakewich H. Segmental defect of the intestinal musculature of a newborn: evidence of acquired pathogenesis. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31:721–5.

- Saha S, Konar H, Chatterjee P, Basu KS, Chatterjee N, Thakur SB, et al. Segmental ileal obstruction in neonates— rare entity. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44:1827–30.

|

|

|

|

|

|