|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Case Report |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

|

|

|

Somika Sethi1, Varsha Manucha1, Deepali Jain1, Prem Chopra1, Pramoj Jindal2

Department of Pathology1 & General Surgery2

Sir Ganga Ram Hospital, Rajinder Nagar,

New Delhi, India 110060

Corresponding Author:

Dr Deepali Jain,

Email: deepalijain76@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.2012.110

48uep6bbphidvals|595 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Neuromuscular and vascular hamartoma (NMVH) is a rare, benign, non-neoplastic lesion mostly affecting the small intestine. It consists of aberrant arrangement of non-epithelial tissue normally occurring in the intestine and has been considered as a hamartoma.[1] The hamartomatous nature of this disorder has been questioned by many authors because identical features may be seen in Crohn’s disease,[2] non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)-associated small intestinal diaphragm disease,[3,4] ischaemic enteritis and radiation enteritis.[1]

Case report

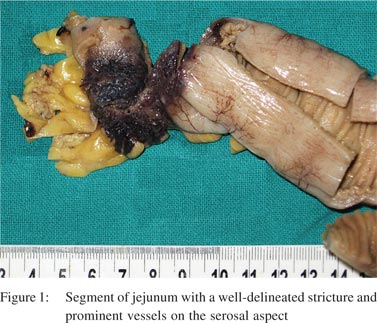

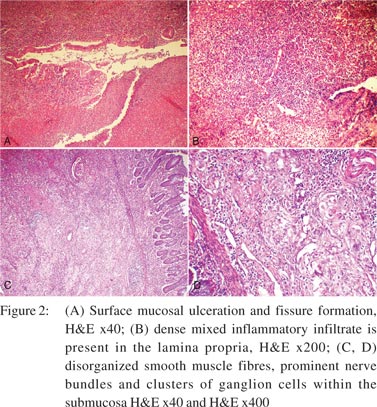

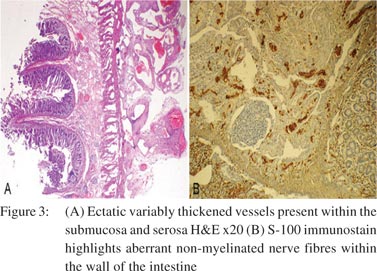

A 28-year-old woman presented with abdominal pain and recurrent vomiting for 1 month duration. On enteroscopy, a single stricture was identified in the jejunum. Barium meal follow-through revealed a stricture causing compression in the mid jejunum. The rest of the bowel was unremarkable. No significant past medical or surgical history was present. The patient underwent a segmental resection with anastomosis. Gross examination revealed a 16 cm segment of the small bowel with a single, well-delineated stricture measuring 2.5 cm × 2 cm. The overlying serosa on the stricture was dusky blue with congestion, haemorrhage and prominent vessels (Figure 1). On opening, there was a circumferential stricture with ulcerated and congested overlying mucosa. Cut section through the stricture revealed thickened and fibrotic wall. Microscopically, focal superficial erosion and ulceration of the mucosa was seen with single fissure formation extending into the submucosa (Figure 2A). The lamina propria was widened with dense lymphoplasmacytic inflammation admixed with sparse eosinophils and neutrophils (Figure 2B). Focal crypt abscesses were observed. However, no architectural disruption was evident. Transmural lymphoid hyperplasia was present without any granuloma formation. The most conspicuous findings were present within the submucosa and subserosa. The submucosa was expanded with neural hyperplasia and presence of large variably sized aggregates of ganglion cells (Figure 2C). Haphazard intertwined proliferating bundles of smooth muscle fibres appear to arise from muscularis mucosae were seen (Figure 2D). There were numerous disorganized ectatic blood vessels recognized within the submucosa and subserosa (Figure 3A). Blood vessels were of variable calibre and showed variable thickness of their walls. No vasculitis or thrombosis was seen. The non-strictured intestinal segment and resected edges were within normal limits. The mesenteric fat showed reactive lymph nodes. S-100 immunostain highlighted proliferating hypertrophied nerve bundles (Figure 3B), whereas CD34 and factor VIII antibodies showed vascular channels. Smooth muscle actin was present in the submucosa, blood vessels and hypertrophied muscularis mucosae. CD68 immunostain did not confirm the presence of either histiocytes or ill-formed granulomas.

A diagnosis of NMVH was made in view of the short history of upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, a single isolated jejunal stricture, endoscopically normal distal bowel, absence of classical hallmarks of Crohn’s disease, viz. skip lesions, prominent fissuring ulcers, granulomas, and crypt architectural disruption with conspicuous mural changes in the form of neuromuscular and vascular proliferation. A comment was made with regard to the prominent inflammatory changes and follow-up of the patient was advised. After 2 year of follow-up, the patient was doing well.

A diagnosis of NMVH was made in view of the short history of upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, a single isolated jejunal stricture, endoscopically normal distal bowel, absence of classical hallmarks of Crohn’s disease, viz. skip lesions, prominent fissuring ulcers, granulomas, and crypt architectural disruption with conspicuous mural changes in the form of neuromuscular and vascular proliferation. A comment was made with regard to the prominent inflammatory changes and follow-up of the patient was advised. After 2 year of follow-up, the patient was doing well.

Discussion

NMVH was first described in two women patients by Fernando and Mcgovern in 1982 as a specific hamartomatous condition of the small intestine.[1] Since then, 9 more cases have been reported in which it is also described as a distinct entity. NMVH occurred in the small intestine in all except three cases—one in the cecum and other two in Meckel’s diverticulum.[5–7] All the cases lacked manifestation of any multisystem disease such as neurofibromatosis or features of inflammatory bowel disease or prolonged intake of NSAIDs.

Patients with NMVH usually present with a history of recurrent episodes of abdominal pain with vomiting or rarely with constipation.[1,6,8] They may present with anaemia due to chronic blood loss from the GI tract.[1,9] There is no known age or sex predilection. Endoscopic, barium studies of the small bowel and CT studies show single or multiple strictures without any demonstrable mechanical cause.[8] Two of the 11 cases had a previous history of surgical procedure and one had a history of treated tuberculosis and radiotherapy, thus raising a question whether NMVH is a post-traumatic or postinflammatory lesion?[1,6]

In agreement with Fernando and Mcgovern,[1] we diagnosed the present case as a hamartomatous lesion independent of any systemic disease. However, Shepherd and Jass[2] proposed NMVH as a part of inflammatory bowel disease and suggested that the pathological features may be those of a chronic burntout form of the disease. Although we observed prominent inflammatory changes with transmural lymphoid hyperplasia, all classical features of Crohn’s disease were lacking. The exact pathogenesis of the disease is not known. The reported association with inflammatory bowel disease and NSAIDassociated small intestinal diaphragm disease indicates that it could be a non-specific reactive lesion.[2–4]

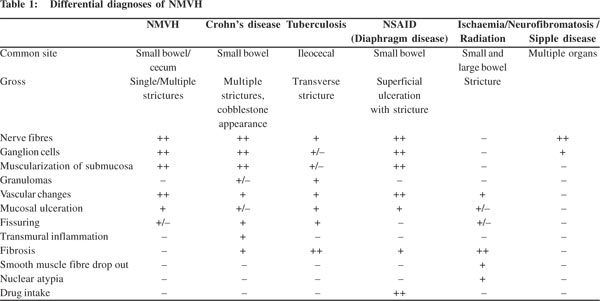

Grossly solitary or multiple strictures or a polypoidal mass have been reported. Microscopically, the abnormalities are seen mainly in the submucosa and subserosa. Mucosa over the narrowing reveals ulcerations or erosions. The lesion consists of bundles of non-myelinated nerve fibres with clusters of ganglion cells, fascicles of smooth muscle fibres merging with muscularis mucosae and hypertrophied muscularis propria. Ectatic variable sized, thick and thin-walled vessels were seen.[1,6,8] The vessels may extend both into the serosa and into the lamina propria. Histopathological changes need to be correlated with clinical and endoscopic findings. The differential diagnosis of NMVH is discussed in Table 1. The salient features which distinguish NMVH from other overlapping disorders are absence of granuloma or fissure formation or transmural inflammation as seen in Crohn’s disease; granulomas (fresh or hyalanized) in tuberculosis; dense fibrosis in radiation and ischaemic enteritis; clinical history of prolonged use of NSAIDs in diaphragm disease. Peutz–Jeghers hamartomas may enter into the differential diagnosis, but differ from NMVH by the characteristic branching core of a muscular tissue derived from the muscularis mucosae expanding toward the luminal surface. As shown in the differential diagnoses, there are only subtle differences between Crohn’s disease and NMVH. In the present case, in contrast to the previously reported cases, prominent inflammation was seen along with mucosal ulceration and focal fissure formation. Transmural inflammation was absent though reactive lymphoid follicles were dispersed throughout the wall of the intestine. Few lymphoid aggregates were present in the wall of ectatic vessels giving an appearance of the lymphangiomatous process. However, in this case, clinical and imaging findings were not in favour of inflammatory bowel disease. The patient had only one stricture and remained well after surgery on follow-up. Therefore, the presence of inflammatory changes cannot preclude the diagnosis of NMVH, especially if clinical and endoscopic findings are correlated.

References

- Fernando SSE, Mcgovern VJ. Neuromuscular and vascular hamartoma of small bowel. Gut. 1982;23:1008–12.

- Shepherd NA, Jass JR. Neuromuscular and vascular hamartoma of the small intestine: is it Crohn’s disease? Gut. 1987;28:1663–8.

- De Petris G, López JI. Histopathology of diaphragm disease of the small intestine: a study of 10 cases from a single institution. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;130:518–25.

- de Sanctis S, Qureshi T, Stebbing JF. Clinical and pathological overlap in nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-related small bowel diaphragm disease and the neuromuscular and vascular hamartoma of the small bowel. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:539–41.

- Stewart IC. Neurovascular hamartoma in a Meckel’s diverticulum. Br J Clin Pract. 1985;39:411–12.

- Shiomi T, Kameyama K, Kawano Y, Shimizu Y, Takabayashi T, Okada Y. Neuromuscular and vascular hamartoma of the cecum. Virchows Arch. 2002;440:338–40.

- Hemmings CT. Neuromuscular and vascular hamartoma arising in a Meckel’s diverticulum. Pathology. 2006;38:173–4.

- Smith CE, Filipe MI, Owen WJ. Neuromuscular and vascular hamartoma of small bowel presenting as inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1986;27:964–9.

- Kwasnik EN, Tahan SR, Lowell JA, Weinstein B. Neuromuscular and vascular hamartoma of the small bowel. Dig Dis Sci. 1989;34:108–10.

|

|

|

|

|

|