|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Conference Proceedings |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Ulcerative colitis, Mayo Score, colonoscopy, proctosigmoidoscopy, pan-colitis |

|

|

|

MK Goenka,1 Sourav Nag,1 Ajay Kumar,2 C Ganesh Pai3

Institute of Gastrosciences,1

Apollo Gleneagles Hospitals,

Kolkata

Gastroenterology and Hepatology2

Indraprastha Apollo Hospital,

New Delhi

Department of Gastroeterology and

Hepatology,3

Kasturba Medical College,

Manipal University,

Manipal, Karnataka, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. MK Goenka

Email: mkgkolkata@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.277

Abstract

It is important to assess the severity of ulcerative colitis (UC) in order to decide the intensity of treatment and predict outcome. The criteria instituted by Truelove and Witts almost 60 years back are still being used. However, they lack a scoring system and offer no clear definition for the moderate group. The criteria with scoring system and endoscopic criteria (Mayo Score) seems to be more useful clinically. Endoscopic assessment is very important and a cautious attempt should always be made even if it enables a limited colonoscopic examination. Proctosigmoidoscopy is advocated at initial stages and after 5 to 7 days. The criteria for severity in general are same for pan-colitis and limited disease.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|736 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disorder involving the colonic mucosa and is characterized by periods of remission punctuated by clinical exacerbation. Disease monitoring includes proper evaluation of clinical and biochemical parameters, severity and extent at endoscopy and histologic activity. Severity assessment aid clinical decisions, offers outcome prognosis, helps evaluate treatment response and is essential for clinical drug trials. The clinical profile including laboratory parameters, endoscopic features or both are usually used to assess severity. Radiological investigations and histological assessment however, have limited role for evaluating the severity of UC.

Severity indices used for UC

Several criteria have been used for last 60 years for assessment of severity of UC.[1] Table 1 shows various severity indices used from time to time.

Clinical criteria for severity

A. Truelove and Witts’

As early as1955, Truelove and Witts’ categorised UC into three classes i.e. mild, moderately severe, and severe based on six clinical and laboratory parameters. [2] (Table 2)

In order to avoid ambiguity Dinesen et al [11] suggested the following clinical parameters to define Acute Severe Colitis.

• > 6 bloody bowel motions /24 hr. AND

• One or more of

• Temperature >37.80C

• Heart rate >90 /min

• Hb<10.5 g/dL

• ESR >30 mm/hr

By using these parameters, it was suggested that d” 25% of UC patients will have acute severe colitis.

B. Montreal classification

Satsangi et al[12] proposed, what is, known as Montreal classification (Table 3). As compared to original the Truelove and Witts’ criteria, this includes abdominal pain as a parameter and defines criteria for moderate disease more clearly. Though these scoring systems are often used clinically, they have some drawbacks. These include the absence of scoring system, non-inclusion of endoscopic findings and the absence of validation. Moreover, it is not enough to classify disease into mild, moderate and severe only. Fulminant colitis, toxic megacolon, severe bleeding and perforation are entities which need to be evaluated and defined as these actually are “super severe” IUC. Extra intestinal manifestation, with the exception of primary sclerosing cholangitis and ankylosing spondylitis, correlate with colitis severity and their presence should therefore be specified while defining severity of UC.

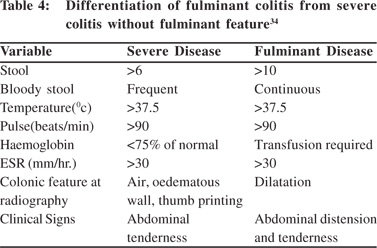

C. Fulminant colitis

Fulminant colitis is the most severe form of UC and its presence needs to be clearly defined because of therapeutic implications. Table 4 gives the criteria to separate this entity from usual severe colitis without fulminant features.

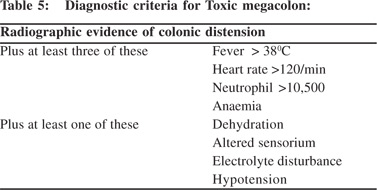

D. Toxic megacolon

Fulminant colitis may get complicated by toxic megacolon (TM).

TM is defined as total or segmental non obstructive marked colonic dilation associated with systemic toxicity. Colonic dilatation <9 cm for cecum and <6 cm for rest of colon (particularly for transverse and right colon) are usually considered for diagnosis of toxic megacolon. TM complicates 1-5% of IUC in its natural history. TM needs to be differentiated from Hirschsprung’s disease and Intestinal pseudo-obstruction.

In these situations colonic dilatation, is not usually associated with systemic toxicity. Table 5 suggests criteria for establishing the diagnosis of TM which holds true even today 45 years after its description by Jalan et al.[13]

E. Perforation and Bleeding

Toxic megacolon can be complicated by colonic perforation, which has a mortality risk of 50%. Perforation in UC, can rarely occur without the existence of TM particularly, in the initial episodes of UC with little or no scarring. Severe bleeding can also complicate UC. 10% of UC may have severe bleeding, while in 3% it may be exsanguinating. Severe bleeding in UC is an indication for urgent colectomy.

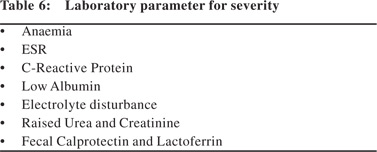

I. Laboratory parameter for severity

Table 6 gives the laboratory parameters often used for assessing severity of UC. These as mentioned above, are usually considered in association with clinical criteria. Neutrophil-derived markers, particularly fecal calprotectin and lactoferrin, have proven to correlate well with mucosal inflammation of UC at a rho range of 0.6–0.8 [14–17]. Fecal level of these markers reflects the mucosal influx of inflammatory cells in the gut. When the level of these markers is low, the presence of active inflammation in the colon is unlikely [16,18–21]. Significant difference in calprotectin in mild, moderate, & severe disease is seen with a sensitivity of 92% & specificity of 80%. Correlation of both these markers have been noted with Mayo Disease Activity Index in UC (p<.0001). [22] In pediatric UC, clinical disease activity assessed with the validated index i.e. PUCAI shows a good correlation with the levels of calprotectin. In a study involving 62 paediatric UC patients, fecal calprotecin value was significantly higher (p<0.001) among patients with active UC (PUCAI e”10) compared to those with inactive disease (PUCAI<10).[23] The data showed a rho value of 0.67 (p=0.009) for correlation between PUCAI and fecal calprotectin[23]. However, the clinical relevance of isolated elevation of calprotectin level in patients with clinical remission is not known. This scenario does not presently warrant escalation of therapy. However, there may be a need for closer monitoring, especially in those with values >800ìg/g[23].

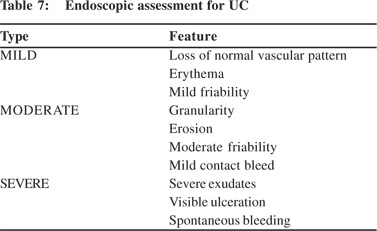

II. Role of endoscopy in determining severity of UC

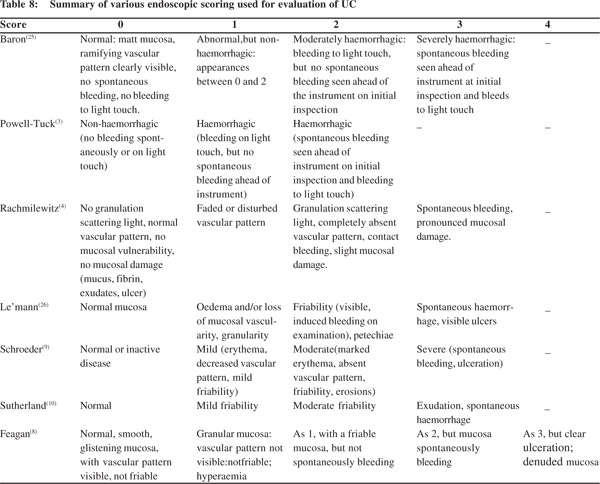

Ileocolonoscopy is very useful for establishing the diagnosis of UC, mapping the extent and assessing the severity of disease. However, in suspected severe colitis “aggressive” colonoscopy should be avoided. Examination is usually limited to sigmoidoscopy particularly when TM is suspected, and bowel preparation should best be avoided in presence of severe colitis. Proximal passage of colonoscope, even if colonoscopy is planned should be abandoned, if severe changes are discovered. Sodium phosphate based bowel preparations can cause artefacts and should be avoided during assessment of severity of UC. Overall correlation of endoscopy with clinical severity is not good except when disease is limited to left colon. If the patient has received rectal treatment for UC, severity at sigmoidoscopy alone may lead to underestimation. In a study by Carbonnel et al,[24] 85 patients were evaluated at endoscopy. Severe disease was defined by presence of extensive deep ulcers, mucosal detachment at ulcer edge and by well shaped ulcers. Of the 46 patients with severe disease, 43 patients had to undergo surgery and only 3 could be managed conservatively. In contrast among 39 patients with moderate disease, 30 patients could be managed conservatively[24]. This study highlights the importance of endoscopy in determining the severity of UC. Baron et al[25] (1964) was first to classify UC at endoscopy. Table 7 gives the criteria for differentiate mild from moderate and severe disease as described by Baron et al(25). Figure 1 illustrates the endoscopic findings in various severity. Table 8 gives a summary of various Endoscopic Scoring used for evaluation of UC.

Mayo Score

Mayo scoring system integrates clinical parameters with endoscopic findings and is the one most commonly used in clinical practice (Table 9)[9].

Act 1 & Act 2 studies on infliximab in UC used Mayo Score. A Mayo score of 0 at 8 wks. of therapy, was associated with 73% chance of clinical remission at 1 year with a high probability of avoiding colectomy (27).While popular, Mayo score has the drawbacks because the physician’s global assessment is somewhat subjective. Moreover the score requires more validation studies.

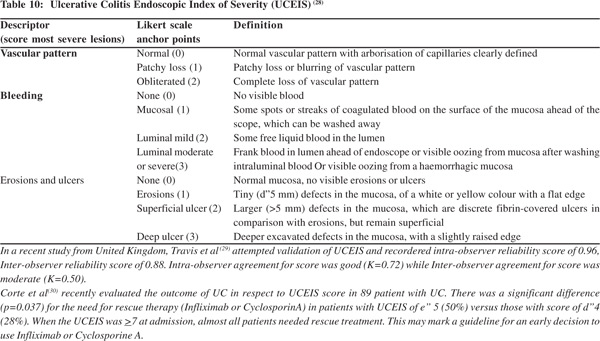

Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS)

UCEIS is one of the recently introduced endoscopic scoring and is being increasingly used (Table 10) [28].

UC in paediatric population

UC in children shares many features with adult-onset disease but disease is often more extensive, more severe and is prone to more flare ups. The therapeutic approach has to be adapted to these particular needs. A clinical scoring system known as the Paediatric Ulcerative Colitis Activity Index (PUCAI) has been developed and validated (Table 11). The PUCAI may be used to determine when it is necessary to escalate therapy in fulminant colitis. It is also used to assess disease activity in clinical trials involving paediatric patients with UC. In a study by Turner et al[31] real-life, prospectively obtained data confirm that the PUCAI is highly feasible by virtue of the noninvasiveness, valid, and responsive index. The PUCAI can be used as a primary outcome measure to reflect disease activity in paediatric UC[31]. Based on the scoring system, pediatric UC has been classified into disease in remission, mildly active, moderately active or severe disease (Table 12). PUCAI score can also prognosticate the disease and act as guidance to upscale the treatment (Table 13)[32]

III. Radiological and histological assessment for severity

Imaging has a limited role in UC. Double contrast barium enema (DCBE) in patients with severe UC often shows features like speculated collar button ulcers, loss of haustra, calibre narrowing, shortening of colon, and pseudopolyp. However DCBE can precipitate toxic megacolon in patient with severe UC and therefore should best be avoided. CT and MRI are rarely used to assess severity of UC. They are less sensitive than barium enema in mild disease but as sensitive as barium enema in severe disease. CT and MRI can however, be useful to detect small perforation and abscess formation around the intestine.

Severity of ulcerative colitis can also be judged by histology but this not commonly used for this purpose[33]. At histology UC can be classified as score 0 (normal histology), score 1 (small foci of lymphocytes), score 2 (edema, vascularity, increased inflammatory cells but intact epithelium), score 3(Severe inflammation with heavy infiltrates, crypt abscess, ulceration, purulent exudates).

Conclusion

It is important to assess the severity of colitis in UC in order to decide intensity of treatment and prognosticate the outcome. Assessment should be based on combination of clinical, lab parameters and endoscopy. Daily physical examination of the patient includes measurement of temperature and pulse rate, recording of stool frequency, consistency and presence of blood in stool. Daily full blood count, ESR, CRP, electrolyte and albumin, plain abdominal x-ray should be included in assessment for severe active ulcerative colitis. Barium studies are not required to assess the severity. Existing clinical classifications lack objectivity and one with scoring system and endoscopic criteria (Mayo Score) seems to be most useful clinically. Terms fulminant colitis and toxic megacolon indicate very severe form of colitis and they should be clearly looked for. While describing severity of disease, presence of extra intestinal complication should also be mentioned, as most of them correlate with severity of intestinal disease. Endoscopic assessment is very important and an attempt keeping safety in mind should always be done to perform at least a limited colonoscopic examination. Proctosigmoidoscopy is advocated at initial stage and after 5 to 7 days. Endoscopically disease could be classified as mild, moderate, and severe. While more work need to be done, the criteria for severity in general are same for pancolitis and limited extent of disease.

References

- Cooney RM, Warren BF, Altman DG, Abreu MT, Travis SP.Outcome measurement in clinical trials for Ulcerative Colitis: towards standardisation; Trials.2007;8:17.

- Truelove SC, Witts LJ. Cortisone in ulcerative colitis; final report on a therapeutic trial. Br Med J. 1955,ii:1041–8.

- Powell-Tuck J, Day DW, Bucknell NA, Wadsworth J, Lennard-Jones JE.Correlations between defined sigmoidoscopic appearances and other measures of disease activity in ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1982,27:533–7.

- Rachmilewitz D. Coated mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid) versus sulphasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomised trial. Br Med J. 1989,298:82–86.

- Lichtiger S, Present DH, KornbluthA, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G et al. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994,330:1841–5.

- Seo M, Okada M, Maeda K, Oh K. Correlation between endoscopic severity and the clinical activity index in ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998,93:2124–9.

- Walmsley RS, Ayres RC, Pounder RE, Allan RN. A simple clinical colitis activity index. Gut. 1998,43:29–32.

- Feagan BG, Greenberg GR, Wild G, Fedorak RN, Pare P, McDonald JW et al. Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis with a Humanized Antibody to the á4â7 Integrin. N Engl J Med. 2005,352:2499–507.

- Schroeder KW, Tremaine WJ, Ilstrup DM. Coated oral 5- aminosalcylic acid therapy for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis, a randomised study. N Engl J Med. 1987,317:1625–9.

- Sutherland LR, Martin F, Greer S, Robinson M, Greenberger N, Saibil F et al. 5-Aminosalicylic acid enema in the treatment of distal ulcerative colitis, proctosigmoiditis, and proctitis.Gastroenterology. 1987,92:1894–8.

- Dinesen LC, Walsh AJ, Protic MN, Heap G, Cummings F, Warren BF et al. The pattern and outcome of acute severe colitis: J Crohns Colitis. 2010,4:431–7.

- Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensus, and implications; Gut.2006;55:749–53.

- Jalan KN, Sircus W, Card WI, Falconer CW, Bruce CB, Crean GP et al. An experience of ulcerative colitis I. Toxic dilation in 55 cases. Gastroenterology. 1969;57:68–82.

- Bunn SK, Bisset WM, Main MJ, Golden BE.Fecalcalprotectin as a measure of disease activity in childhood inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001,32:171–7.

- Bunn SK, Bisset WM, Main MJ, Gray ES, Olson S, Golden BE. Fecalcalprotectin: validation as a noninvasive measure of bowel inflammation in childhood inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001,33:14–22.

- Canani RB, Terrin G, Rapacciuolo L, Miele E, Siani MC, Puzone C et al.Faecal calprotectin as reliable non-invasive marker to assess the severity of mucosal inflammation in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis.2008,40:547–53.

- DiamantiA, Colistro F, Basso MS, Papadatou B, Francalanci P, Bracci F et al.Clinical role of calprotectin assay in determining histological relapses in children affected by inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1229–35.

- Canani RB, Rapacciuolo L, Romano MT, Tanturri HL, Terrin G, Mangusso F et al.Diagnostic value of faecal calprotectin in paediatric gastroenterology clinical practice. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:467–70.

- Walker TR, Land ML, Kartashov A, SaslowskyTM,Lyerly DM, Broone JH et al. Fecallactoferrin is a sensitive and specific marker of disease activity in children and young adults with inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44:414–22.

- Aomatsu T, Yoden A, Matsumoto K, Kimura E, Inouc K, Andoh A et al. Fecalcalprotectin is a useful marker for disease activity in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56:2372–7.

- Henderson P, Casey A, Lawrence SJ, Kennedy NA, Kingstone K, Rogers P et al. The diagnostic accuracy of fecalcalprotectin during the investigation of suspected pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012,107:941–9.

- Vieira A, Fang CB, Rolim EG, Klug AW, Steinwurz F, Rossini LG et al; Inflammatory bowel disease activity assessed by fecalcalprotectin and lactoferrin: correlation with laboratory parameters, clinical, endoscopic and histological indexes. BMC Res Notes 2009,2:221.

- Kolho KL, Turner D. FecalCalprotectin and Clinical Disease Activity in Pediatric Ulcerative Colitis. ISRN Gastroenterol. 2013;2013:179024.

- Carbonnel F, Lavergne A, Lemann M, Bitoun A, Valleur P, Hautefeuille P et al. Colonoscopy of acute colitis. A safe and reliable tool for assessment of severity. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:1550–7.

- Baron JH, Connell AM, Lennard-Jones JE. Variation between observers in describing mucosal appearances in proctocolitis. Br Med J. 1964,11:89–92.

- Lémann M, Galian A, Rutgeerts P, Heuverzwijn RV, Cortot A, Viteau JM et al. Comparison of budesonide and 5-aminosalicylic acid enemas in active distal ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:557–62.

- Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Martzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383–95.

- Travis SP, Schnell D, Krzeski P, Abreu MT, Attman DG, Colombel JF et al. Developing an instrument to assess the endoscopic severity of ulcerative colitis: the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS). Gut. 2012;61:535–42.

- Travis SP , Schnell D, Krzeski P, Abreu MT, Attman DG, Colombel JF et al. Reliability and initial validation of the ulcerative colitis endoscopic index of severity. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:987–95.

- Corte C, Fernandopulle N, Catuneanu A, Burger D,Cesarini M, Keshav S et al.Correlation between the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) and outcomes in acute severe ulcerative colitis. Poster presentations: clinical: Diagnosis and outcome. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013.

- Turner D, Hyams J, Markowitz J, Lerer T, Mack DR, Evans J et al. Appraisal of the pediatric ulcerative colitis activity index (PUCAI). Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:1218–23.

- Turner D, Mack D, Leleiko N, Walters TD, Uusoue K, Leach ST et al. Severe pediatric ulcerative colitis: a prospective multicentre study of outcomes and predictors of response. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2282–91.

- Neumann H, Vieth M, Gunther C, Neufert C, Kiessdich R, Grauer M et al. Virtual chromoendoscopy for prediction of severity and disease extent in patients with inflammatory bowel disease:a randomised controlled study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:1935–42.

- Portela F, Lago P. Fulminant colitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2013;27:771–82.

|

|

|

|

|

|