|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Short Reports |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Transrectal, ultrasound, catheter |

|

|

Anuj Thakral*, Ramaniwas Sundareyan*, Sheo Kumar*, Divya Arora**

Department of Radiology*,

Department of Laboratory Hematology**,

Sanjay Gandhi Post Graduate

Institute of Medical Sciences,

Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh – 226014,

India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Anuj Thakral

Email: anujthakral@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.254

Abstract

The transrectal approach to draining deep-seated pelvic collections may be used to drain intra-abdominal collections not reached by the transabdominal approach. We discuss 6 patients with such pelvic collections treated with transrectal drainage using catheter placement via Seldinger technique. Transrectal drainage helped achieve clinical and radiological resolution of pelvic collections in 6 and 5 of 6 cases, respectively. It simultaneously helped avoid injury to intervening bowel loops and neurovascular structures using real-time visualization of armamentarium used for drainage. Radiation exposure from fluoroscopic/CT guidance was avoided. Morbidity and costs incurred in surgical exploration were reduced using this much less invasive ultrasound guided transrectal catheter drainage of deep-seated pelvic collections.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|712 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Percutaneous catheter drainage (PCD) is the standard of care in the management of intra-abdominal collections where immediate surgery is not indicated.[1] Pelvic collections are challenging for a trans-abdominal approach to drainage.[2]

Alternative approaches (trans-rectal, trans-vaginal and transgluteal) can be used to circumvent risks associated with transabdominal drainage in such cases. Among these, the transrectal route is less painful, better tolerated and with proper technique, high clinical cure rates can be attained with fewer complications.[3] In this article we discuss 6 cases with pelvic collections, treated with trans-rectal drainage, and thereby highlight issues pertaining to this method of treatment.

Technique of transrectal drainage

A review of pre-procedure imaging including transabdominal ultrasound and CECT abdomen was performed. Only patients found unsuitable for safe transabdominal drainage were Short Reports evaluated further for the transrectal approach. The patient’s coagulation profile (prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, international normalized ratio and platelet count) was reviewed. Those with deranged coagulation profile (INR >1.5 &/or platelet count < 50,000/mm3) were taken up for procedure following correction of coagulation status. All patients received broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics and rectal enema prior to procedure. Informed consent was taken. An 8-4 MHz end-fire probe (3D9-3v, HD 11 XE, Philips) covered with a condom and with a biopsy guide attached was used for transrectal sonographic guidance with patient in left lateral decubitus position. The collection was localized and 18G Chiba needle (Cook Inc., Bloomington, USA) was advanced after administration of 10ml of local anesthetic (Inj. Lignocaine 2%).

Samples for culture were obtained. A 0.9 mm (0.035 in.) amplatz ultra-stiff guidewire (Cook Inc., Bloomington, USA) was inserted through the needle and coiled within the abscess cavity. After serial dilatations with a Coons dilator, a self-retaining locking loop catheter (Cook Inc., Bloomington, USA) was inserted into the collection.

All catheters were taped to the buttocks and attached to a leg bag through a tube for gravity dependent drainage. Catheter patency, the amount drained and the patient’s clinical condition were assessed daily. All catheters were flushed with 5-10 ml of normal saline every 8 hours to maintain patency.

Results

Over a one-year period, six patients with deep-seated pelvic collections of varied etiology underwent transrectal sonographically guided catheter drainage. Clinical indications, site of collection, size and type of catheter, nature of aspirate, culture results and clinical course following catheter placement are shown in Table 1.

Discussion

Intra-abdominal collections commonly occur through various causes (post surgical, infective and inflammatory conditions). Interventional drainage by minimal invasive methods (ultrasound or CT guided single time or catheter drainage) saves the need for surgical exploration, associated complications and surgery related mortality and morbidity. These collections are routinely drained by the transabdominal approach. Unlike other intra-abdominal collections, deep seated pelvic collections pose certain problems in percutaneous trans-abdominal drainage. These include risk of injury to intervening bowel and neurovascular structures.[2] To overcome these, alternative approaches like trans-rectal, trans-vaginal and trans-gluteal routes can be used. Major drawbacks of the transgluteal approach include possible injury to neurovascular structures in the greater sciatic notch and catheter kinking.

Trans-vaginal approach is possible only in sexually active females (see case 1), and provides limited accessibility to presacral region with poor patient compliance.[3] The transrectal route is preferred as it is safer, less painful, and is more feasible, and accessible to the presacral region. The procedure is better tolerated with higher clinical cure rates and fewer complications.[4]

Trocar technique of catheter placement is simpler and less time consuming.[2,5] But associated tissue drag increases chance of injury to adjacent organs.[5] Seldinger technique is preferred for being less traumatic with accurate catheter placement. Better sonographic visibility of newer guidewires obviates

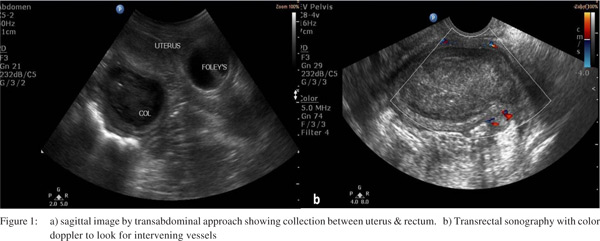

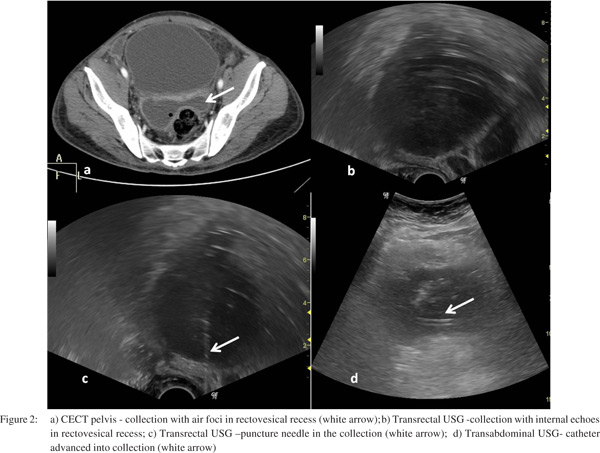

need for additional flouroscopic guidance and allows manipulations under sonographic guidance itself. Sonographic guidance for selecting site of entry into pelvic collection with real-time visualization of advancing armamentarium for drainage (needles, wires & catheters) helps avoid intervening vascular channels, preventing hemorrhage (Figure 1b). It also proves more cost effective, is more easily available and free of radiation exposure associated with CT guidance. (Figure 2)

Local anesthesia with or without mild sedation prove sufficient for this procedure (all cases in our series). But children and uncooperative patients may require general anesthesia. Minimum size of initial catheter for proper drainage should be atleast 10F (especially for infected collection). Locking loop catheters are available till 14 F.

Catheter patency, amount drained and patient’s condition need to be assessed daily. Catheters need 8 hourly flushing with 5-10 ml of normal saline to maintain patency. Catheter removal can be planned when daily output falls below 10 ml and patient improves clinically. When signs of infection persist with reduced catheter output, clogging, displacement or kinking should be looked for. Further imaging, especially CT, helps confirm catheter position and amount of residual collection. Repositioning or replacement with larger bore catheter may be required.

Deep seated pelvic collections resolved in all cases (except one where 50ml of organized collection persisted) in our series. All patients (including one with residual persisting pelvic collection) showed resolution of clinical symptoms justifying the transrectal drainage procedure. Microbial culture from transrectal drain helped confirm the culprit pathogen and modify antibiotic regimen for further management. No complications were reported in our series, as also in other series.[6,7]

Spontaneous catheter dislodgment was reported in one series.[8] In conclusion, ultrasound guided transrectal catheter drainage is a safe, effective, and radiation free technique for drainage of deep seated pelvic collections that helps avoid extensive surgical exploration and drainage.

References

- Johnson WC, Gerzof SG, Robbins AH, Nabseth DC. Treatment of abdominal abscesses: comparative evaluation of operative drainage versus percutaneous catheter drainage guided by computed tomography or ultrasound. Ann Surg. 1981;194:510–20.

- Harisinghani MG, Gervais DA, Hahn PF, Cho CH, Jhaveri K, Varghese J, et al. CT-guided transgluteal drainage of deep pelvic abscesses: indications, technique, procedure-related complications, and clinical outcome. Radiographics. 2002;22:1353–67.

- Feld R, Eschelman DJ, Sagerman JE, Segal S, Hovsepian DM, Sullivan KL.Treatment of pelvic abscesses and other fluid collections: efficacy of transvaginalsonographically guided aspiration and drainage. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;163:1141–5.

- Hovsepian DM, Steele JR, Skinner CS, Malden ES. Transrectal versus transvaginal abscess drainage: survey of patient tolerance and effect on activities of daily living. Radiology. 1999;212:159–63.

- Varghese JC, O’Neill MJ, Gervais DA, Boland GW, Mueller PR.Transvaginal catheter drainage of tuboovarian abscess using the trocar method: technique and literature review. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:139–44.

- Nosher JL, Needell GS, Amorosa JK, Krasna IH. Transrectal pelvic abscess drainage with sonographic guidance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:1047–8.

- Alexander AA, Eschelman DJ, Nazarian LN, Bonn J.Transrectal sonographically guided drainage of deep pelvic abscesses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:1227–30.

- Ryan RS, McGrath FP, Haslam PJ, Varghese JC, Lee MJ. Ultrasound-guided Endocavitary Drainage of Pelvic Abscesses: Technique, Results and Complications. Clinical Radiology. 2003;58:75–9.

|

|

|

|

|

|