|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Short Report |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Boerhaave 's syndrome, late presentation, primary reinforced repair |

|

|

Amit Ganguly, Manish Porwal, Jagdish Khandeparkar

Department of Surgical Gastroenterology and Laparoscopic Surgery1,

Cardio-Vascular Thoracic Surgery2

CHL–Hospital, Indore, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr Ganguly Amit

Email:dramitganguly@rediffmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.282

48uep6bbphidvals|1346 48uep6bbphidcol2|ID 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Boerhaave’s syndrome (BS) or spontanous esophageal perforation is an uncommon disease entity. Though it is called spontaneous, it is invariably due to barotrauma. The adjective spontaneous signifies that it not secondary to trauma , instrumentation or foreign body.[1] The usual mechanism believed responsible for perforation is sphincter muscle incoordination , which causes failure of the cricopharynx to relax, resulting in sudden increase in intra-luminal pressure in the esophagus. The perforation usually occurs in the left posterolateral aspect of the distal esophagus, which is considered the area of weakness.[2]

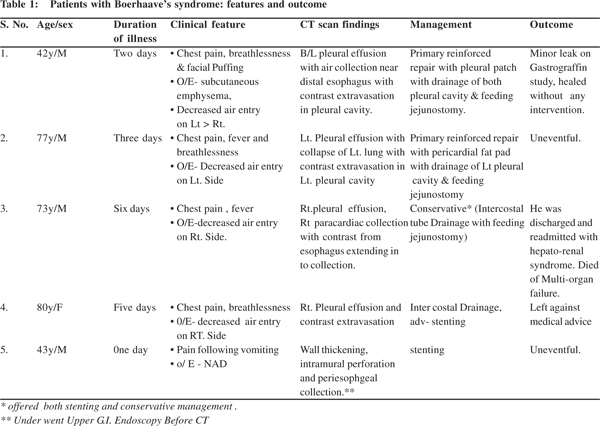

We present our experience of management in patients of BS presenting 24 hours after onset of symptoms. During the period of 2010 -2014, we treated 5 patients of spontaneous esophageal perforation. The clinical features, contrast enhanced computerized tomography (CECT) findings, treatment and outcome are summarized in the Table 1.

Case report

Two patients (Patients 1 and 2) were resuscitated and taken up for surgery within six hours of admission. Both underwent left thoracotomy with primary reinforced repair. Post operatively they were electively intubated for 24 hours. A feeding jejunostomy was initiated after 48 hr. Gastro-graffin study was done on 8th post operative day. Patient 1 showed leak, which resolved without any intervention. His left intercostal drainage (ICD) was removed after resolution of the leak. All through this period he was on feeding jejunostomy feeds. The mean duration of hospital stay for this group of patient was 2 weeks. Patient 3 was HbsAg +ve with deranged INR, and low platelet count. Imaging revealed small shrunken liver, moderate ascites and collateral at porta. Surgery was deemed high risk. Intercostal drainage tube insertion and feeding jejunostomy were performed under local anasthesia. He was also offered endoscopic stenting but the family refused. He was discharged with intercostal drainage tube and feeding Jejunostomy insitu. He had to be readmitted after 6 weeks with hepatic decompensation and azotemia. He died of multi-organ failure. Patient 4 was an elderly lady, who at the time of diagnosis was not fit for any operative intervention. Intercostal drainage tube was inserted at the bed side. She was advised stenting but declined and left against medical advice.

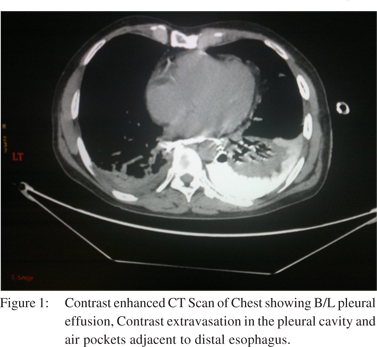

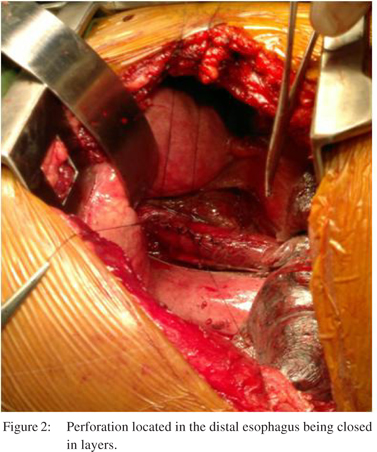

Patient 5 was first seen in the out patients’ department before being referred to us, where he presented with complaints of pain in epigastrium after a bout of vomiting. Acid peptic disease was suspected. At the commencement of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE), suspicious perforation in the distal esophagus was identified. Endoscopy was terminated immediately. The patient was admitted and CT scan done. In view of the minimal peri-esophageal mediastinal collection he was offered stenting. He was discharged after 5 days and subsequent CT scan at 6 weeks showed resolution of collection. It is our policy to offer surgery to all patients if contrastenhanced CT scan shows free contrast extravasation with gross mediastinal contamination (Figure 1) and if the patient is fit for surgery (Figure 2). A patient who is stable with CT scan showing minimal mediastinal collection without contrast extravasation is offered endoscopic stenting. However if the patient is not fit for surgery then we offer endoscopic stenting in conjunction with intercostal drainage and feeding jejunostomy even when CT shows gross mediastinal contamination and free contrast extravasation with the idea that constant mediastinal soiling will be avoided.

Discussion

BS has mortality of 20-40%, highest amongst all causes of oesophageal perforation. Left untreated, it is invariably fatal.[2,3] The high mortality is not only because of relative late detection in contrast to instrumental perforation but also because of release of acid, enzymatic juices and micro-organisms with high pressure leading to widespread mediastinal and pleural contamination.[4]

The presentation is often non specific, leading to diagnostic dilemma. Macklar’s triad of chest pain, vomiting and subcutaneous emphysema may not be seen in all patients. It was seen in only one of our patients. It is not uncommon to see BS misdiagnosed as diaphragmatic hernia, myocardial infarction, or perforated duodenal ulceration before being referred to a tertiary center for management.[2,5] Three of our five patients were being treated as cases of pleural effusion before coming to us.

We have used multi slice helical CT scan of chest and upper abdomen with contrast for diagnosis. The findings in CECT suggestive of esophgeal perforation are contrast extravasation, periesophgeal air collection and pleural effusion. Published literature shows dominance of left pleural effusion but isolated right sided effusion is also noted, as seen in patient 3. Use of contrast esophagography may give false negative rates of 10% in detecting esophageal perforation.[6] As the disease is rare no consensus exists on the treatment modality. All options, conservative, endoscopic and surgical management have been considered. In the absence of any level I evidence no clear cut management guidelines exist.[2] Though most authors believe that surgery is the primary treatment modality, the type of surgery remains debatable. Options vary from primary repair to esophagectomy and cervical Esophagogastric anastomosis. Single stage Esophgectomy and cervical anastomosis is proposed as the first line of treatment in the setting of late presentation to prevent leak from suture line and resultant mediastinal sepsis. Esophageal diversion and exclusion is suitable for the cases with extensive devitalisation of oesophagus.[4,7]

The traditional philosophy recommends primary repairs only within the first 24 hours. The success of primary repair in delayed cases (duration of perforation > 24 hours) is still not well established.[8] Various authors have challenged this dogma and have reported excellent results with reinforced primary repair even in delayed cases.[9,10,11,12]

Contrasting results from different authors perhaps call for meticulous technique for repair of these perforations.[9] Thoracotomy on the side of perforation not only provides good access but is also useful in thorough mediastinal debridement and lavage.[13] The mucosa and submucosa need to be entirely exposed by doing esophagomyotomy on either side of the perforation, this enables debridement of edematous and nonviable edges. Perforation can be closed in one or two layers. Reinforcement of repair with healthy tissue making sure not to cover the esophagus circumferentially decreases postoperative leak rates. A wide range of tissue e.g. pleura, diaphragm, pericardium, Intercostal muscle etc has been used by various authors to reinforce the repair. The chest is closed after full lung expansion.[3] A feeding jejunostomy was done, so as to initiate early enteral feeding, this also ensures enteral nutrition in case of leak.

Minor leaks after primary repairs usually behave as controlled fistula. In the absence of mediastinal sepsis and with proper drainage, most heal without any further intervention and the outcome is not unsatisfactory.[12]

Endoscopic stenting for selected group of patients with minimum mediastinal contamination is an attractive option, which obviates the need for surgery.[14]

There is paucity of data regarding longterm outcome of these patients in literature. D’ Journo et al reported mild GERD and nonspecific motor disorder in six out of seven of their patients on 24 hour pH monitoring and manometry.[1] None of our patients complained of dysphagia or increased frequency of reflux symptoms after a follow up of two years.

In conclusion, BS is difficult to diagnose and treat. A high index of suspicion is essential to diagnose it early as the outcome is dependent on the time lapse between perforation and institution of therapy. A multislice helical CT scan with oral and I/V contrast should be used to establish the diagnosis. We believe that acceptable morbidity and mortality rates can be achieved with primary reinforced repair. This along with the fact that it preserves the native esophagus and provides good quality of life in the long run makes it an attractive option, and should thus not be restricted to patients presenting within 24 hours, especially in a developing country setting like ours where the time gap between patients seeking medical advice and reaching a tertiary center is considerable.

References

- Janjua KJ. Boerhaave’s syndrome. Postgrad Med J. 1997;73:265–70.

- de Schipper JP, Pull ter Gunne AF, Oostvogel HJ, van Laarhoven CJH. Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus: Boerhaave ‘s syndrome. Dig Surg. 2009;26:1–6.

- Vial CM, Whyte RI. Boerhaave ‘s syndrome : Diagnosis and treatment. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:515–24.

- Kollmar O, Lindemann W, Richter S, Steffen I, Pistorius G, Schilling MK .Boerhaave’s syndrome: Primary repair vs. esophgeal resection – case report and meta analysis of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:726–34.

- Sutcliffe RP, Forshaw MJ, Datta G, Rohatgi A, Strauss DC, Mason RC, et al. Surgical management of Boerhaave’S syndrome in a tertiary oesophagogastric centre. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:374–80.

- Ghanem N, Altehoefer C, Springer O, Furtwanglar A, Kotter E, Schafer O, langer M .Radiological Findings in Boerhaave’s syndrome. Emerg Radiol. 2003;10:8–13.

- Gupta NM, Kaman L: Personal Management of 57 Consecutive Patients with Esophageal Perforation. Am J Surg. 2004;187:58–63.

- Teh E, Edwards J, Duffy J, Beggs D. Boerhaave‘s syndrome: A Review Of Management And Outcome. Interact Cardiovascular Thorac Surg. 2007;6:640–3.

- Wright CD, Mathisen DJ, Wain JC, Moncure AC, Hilgenberg AD, Grillo HC. Reinforced primary repair of thoracic esophageal perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:245–8.

- Lawrance DR, Ohari SK, Moxon RE, Townsend ER, Fountain SW. Primary Esophageal repair for Boerhaave ‘s syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:818–20.

- Jougon J , Mcbride T, Delcambre F, Minniti A, Velly JF. Primary esophageal repair for Boerhaave ‘S Syndrome whatever the free interval between perforation and treatment. Eur J Cardio-Thorac Surg. 2004;25:475–9.

- Cho S, Jheon S, Ryu KM, Lee EB. Primary esophageal repair in Boerhaave‘s syndrome. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:660–3.

- Haveman JW, Nieuwenhuijis VB, Muller Kobold JP, van Dam GM, Plukker JT, Hofker HS. Adequate debridement and drainage of the mediastinum using open thoracotomy or video assisted thorascopic surgery for Boerhaave ‘S Syndrome. Surg Endo. 2011;252492–7.

- Kiev J, Amendola M, Bouhaidar D, Sandhu BS, Zhao X, Maher J. A management algorithm for esophageal perforation . Am J Surg. 2007;194:103–6.

- D’Journo XB, Doddoli C , Avaro JP, Lienne P, Giovannini M.A, Giudicelli R, et al. Long term Observation and functional state of the esophagus after primary repair of spontaneous esophageal rupture. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;81:1858–62.

|

|

|

|

|

|