|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Quarterly Reviews |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Sphincter of Oddi disorder (SOD), idiopathic pancreatitis, sphincter of Oddi manometry (SOM), post-cholecystectomy syndrome (PCS), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) |

|

|

S Kumar, M Agrawal, SK Bhartiya, S Basu, VK Shukla

Department of General Surgery,

Institute of Medical Sciences,

Banaras Hindu University,

Varanasi - 221 005,

India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. V. K. Shukla

Email: vkshuklabhu@gmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.276

Abstract

Sphincter of Oddi disorder (SOD) is a part of functional gastrointestinal disorder which is a non-calculous obstructive disorder. This disease is more common in middle-aged women with a prevalence of around 1.5% but in patients with post-cholecystectomy syndrome (PCS) the prevalence rate is markedly higher (9-55%). This high variability maybe attributed to lack of uniformity in patient selection criteria, definition of SOD, and the diagnostic method used. Abdominal pain is the most common symptom occurring due to obstruction at the SO leading to ductal hypertension, ischemia from spastic contraction and hypersensitivity of papilla. Clinical diagnosis of SOD can be achieved by Rome III criteria. Various classifications are used (Milwaukee billiary and modified Milwaukee group classification) for billiary and pancreatic SOD. Not a single non-invasive method is diagnostic. Sphincter of Oddimanometry (SOM) is the gold standard method for evaluating and deciding the management of an SOD patient. The symptomatic relief rate varies from 55% to 95%, so risk-benefit ratio should be evaluated with each patient.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|1340 48uep6bbphidcol2|ID 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD) is a part of functional gastrointestinal disorders and is defined as a benign, noncalculous obstructive disorder that occurs at the level of the SO.[1-2] In the past, many terms have been used interchangeably with SOD like papillary stenosis, ampullary stenosis, biliary dyskinesia, and post-cholecystectomy syndrome (PCS).[3] PCS is actually a misnomer, as SOD can clearly occur with an intact gall bladder. PCS can be defined as persistent or recurrent upper abdominal pain (usually right) following cholecystectomy and may be caused by GERD, gastroparesis, visceral hyperalgesia, retained CBD stones, bile duct injuries and bile leaks[4]. These causes of PCS have to be ruled out if a diagnosis of SOD is to be considered in such patients. A post-cholecystectomy case may present with the complaint “Doctor, it feels like my gall bladder is back!”[5]. Physical examination and USG reveal no abnormality. Such a situation becomes very embarrassing for both surgeon and patient. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction is an entity which may lead to this.

In the current scenario, with gallstone disease as common as it is and paucity of diagnostic tests for SOD, it is very difficult for a surgeon to even consider the diagnosis of SOD in a patient of cholelithiasis. Thus we need to expand our knowledge of SOD.

Epidemiology

The disease prevalence is more common in middle-aged females[2] i.e. the same group as that for cholelithiasis although it can occur in paediatric patients or adults of any age. Its prevalence in the general population has been reported as around 1.5%and is associated with significant effects on the quality of life[6]. SOD in patients with gallbladder has been studied mainly by two groups. Guelrud and colleagues studied it in patients with symptomatic gallstones and normal CBD, and diagnosed SOD in 4.1% to 40% cases corresponding with normal and elevated alkaline phosphatase levels[7]. Ruffolo and colleagues evaluated patients with symptomatic biliary disease but no gallstone and diagnosed SOD in 53%[8].

In the post-cholecystectomy group of people SOD prevalence is 1%, quite similar to that in the general population but in patients with PCS the rate is markedly higher (9-55%).[9] Such high variability could be attributed to lack of uniformity in patient selection criteria, definition of SOD, and diagnostic methods used.SOD has been shown to involve biliary or pancreatic sphincter or both. Eversman and colleagues found 19% pancreatic, 11% biliary and 31% both sphincter involvement.[10] Aymerich and colleagues found involvement of unilateral sphincter in 41% and bilateral in 40%[11].The involvement of pancreatic sphincter i.e. pancreatic SOD has been documented in 15% to 72% of patients with recurrent pancreatitis, previously labelled as idiopathic[12].

Anatomy and physiology

British anatomist Francis Glisson (1595-1677), who carried out important work on the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tract, especially of the liver was the first to describe this sphincter but it was the work of Ruggero Oddi, an Italian anatomist that recognized it as a distinct physiological entity in 1887[13].

The sphincter of Oddi represents a segment of fusion of smooth muscles surrounding the end of the CBD and the main pancreatic duct at the level of the ampulla of vater, with major and minor papilla which projects 1cm into the duodenum as major papilla with an orifice of 1mm.Edward A Boyden proved that the embryologic development of SO is distinct from the muscles of the duodenum. He also described three parts of SO: the sphincter choledochus (having a superior and inferior part), the sphincter pancreatic us and the sphincter ampullae[14]. The preampullary part of the sphincter was recognized as the principal muscle involved in the functional activity of the sphincter and labelled as Boyden’s sphincter. Sphincter of oddi (SO) lies almost entirely within the wall of duodenum in an oblique course, with a length of 6 -10 mm. The blood supply to the SO is provided by a plexus formed between anterior and posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal arteries which are branches of the retroduodenal artery. Normally the papillary orifice lies anywhere from the retroduodenal artery but in 5% population this retroduodenal artery lies within 3cm of major papilla making it susceptible to injury during sphincterotomy.

The function of the SO is to regulate the flow of bile and pancreatic juices into the duodenum, to help in filling the gallbladder during fasting and to maintain a sterile intraductal environment by preventing duodeno-ductal reflux. This is achieved by phasic contractile activity and static basal pressure[15].These phasic waves have a frequency of4-5 per minute, duration of 4-6seconds and peak pressure of 100-150 mmHg while the basal pressure is maintained approximately 15 mmHg higher than in duodenum[16].

A majority of these contractions are ante grade, facilitating the flow of juices into the duodenum. Some are spontaneous and retrograde. These retrograde contractions are increased and responsible for SOD in 50% cases.[17]The phasic contractions correlate with the migrating motor complexes during fasting and show an increase in frequency just before phase 3 of duodenal activity. This prevents bile crystal formation during fasting. After feeding, the sphincter tone as well as the amplitude of contractions decreases. The SO has both hormonal and neural influence.

Cholecystokinin is the main stimulus for gallbladder contraction and SO relaxation following meals[18]. Secret in, NO, VIP are some other locally acting factors helping in relaxing SO. Drugs like atropine, glucagon, nitro-glycerine and calcium channel blockers relax SO while narcotics stimulate it[19].Parasympathetic vagal fibres provide stimulating effect on the SO while sympathetic fibres from splanchnics are mostly inhibitory. There is a close relationship between motor activity of SO and gallbladder, still even after liver transplantation presence of intact motility of SO suggest that the innervations are not essential for SO motility[20].

Etiopathogenesis

The term SOD encompasses two clinically indistinguishable entities[21]:

a) SO stenosis: This represents the static anatomical blockage of SO due to chronic inflammation and fibrosis (incidence is 2-3%) from various conditions like choledocholithiasis, pancreatitis, traumatic surgical manipulation, nonspecific inflammatory conditions, juxtapapillary diverticula, etc. Microlithiasis, as a cause of transient obstruction has now been ruled out due to its similar incidence in SOD and controls[22].

b) SO dyskinesia: This represents the intermittent functional blockage of SO due to spasm, hypertrophy, or denervation. It presents with elevated resting basal pressures, increased frequency of phasic and retrograde contractions[23]. A paradoxical response to CCK, with failure to completely obliterate phasic contractions has been observed more frequently in SOD patients. Low levels of NO and VIP have also been demonstrated. SOD patients also exhibit increased rate of non-gastrointestinal complains and childhood sexual abuse as compared to controls, similar to that seen in irritable bowel syndrome[24]. Visceral hyperalgesia and psychiatric factors are thus associated with both irritable bowel syndrome and SOD especially type III, demonstrating the functional nature of this disease[25].

How does SOD cause pain?

It is postulated that obstruction at SO leading to ductal hypertension, ischemia from spastic contractions and ‘hypersensitivity’ of the papilla may act alone or in concert towards genesis of pain. So, the etiology is not entirely clear.

Clinical presentation

Abdominal pain is the most common symptom and presents in the epigastric and/or right upper quadrant of abdomen and last for 30 minutes to hours. It may radiate to the back or shoulder and may be accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Physical examination is mostly unremarkable. The best way to

a clinical diagnosis of SOD can be achieved by following the Rome criteria[26]. The latest version of this, the ROME III criteria was presented at a symposium in Los Angeles, in May 2006. Rome III divides the functional gastrointestinal disorders into the following six categories:

A. Functional esophageal disorders

B. Functional gastroduodenal disorders

C. Functional bowel disorders

D. Functional abdominal pain syndrome

E. Functional gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi disorders

F. Functional anorectal disorders

Here we are describing the E Category which helps us to diagnose and differentiate between the three closely related disorders:

E. Functional gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi disorders

• Diagnostic criteria: Pain in epigastrium and/or right upper quadrant and all of the following:

— Episodes lasting 30 minutes or longer

— Recurrent symptoms

— Pain builds up to a steady level

— Moderate to severe enough to interrupt the patient’s daily activities or lead to an emergency department visit

— Not relieved by bowel movements

— Not relieved by postural change

— Not relieved by antacids

— Exclusion of other structural disease

• Supportive criteria: pain with one or more of the following:

— Nausea and vomiting

— Radiation to the back and/or right infra subscapular region

— Awakening from sleep in the middle of the night

E1. Functional Gallbladder Disorder

• Diagnostic criteria:all of the following:

— General criteria for functional gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi disorder

— Gallbladder is present

— Normal liver enzymes, conjugated bilirubin, and amylase/lipase

The motility disorder of the gallbladder can be caused either by metabolic abnormalities or by a primary motility alteration.

It is usually suspected after gallstones or other structural abnormalities have been excluded. Diagnosis of functional disorder is confirmed by a reduced ejection fraction induced by cholecystokinin at cholescintigraphy and after disappearance of the symptoms (recurrent biliary pain) after cholecystectomy.

The following criteria are used for this diagnosis[27]:

a. Absence of gallstones, biliary sludge, or microlithiasis.

b. Gallbladder ejection fraction less than 40% using continuous intravenous cholecystokinin octapeptide

infusion over a 30-minute period.

c. Absence of recurrent pain abdomen for longer than 12 months after cholecystectomy.

Gallbladder dysfunction is suspected in the absence of significant abnormalities in the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum. To exclude microlithiasis as a cause, a careful microscopic examination of gallbladder bile should be performed.

E2. Functional Biliary SOD

— Diagnostic criteria: both the following should be present

• Criteria for functional gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi disorder

• Normal amylase/lipase

— Supportive criterion

• Elevated serum transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, or conjugated bilirubin temporarily related to at least two pain episodes.

Biliary-type SO dysfunction is more frequently recognized in post-cholecystectomy patients. Both functional disorders of the gallbladder and/or biliary SO produce similar patterns of pain. SO dysfunction may exist in the presence of an intact biliary tree with the gallbladderinsitu.8 Because the symptoms of SO are not easily distinguished from those of gallbladder dysfunction, diagnosis of SO dysfunction is usually made following cholecystectomy or, less frequently, after functional disorder of the gallbladder has been excluded by appropriate investigations (normal ejection fraction).

E3. Functional pancreatic SOD

— Diagnostic criteria: both the following should be present

Criteria for functional gallbladder and sphincter of Oddi disorder and elevated amylase/lipase

In the absence of common causes of pancreatitiss (gallbladder stones, alcohol abuse), or any other uncommon causes, the diagnosis of idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis should be considered. The association between SO dysfunction and recurrent episodes of pancreatitis has been reported by Tarnasky et al (1998).[28]

Classification

The Classical Milwaukee Biliary Group Classification (Hogan- Geenen classification; 1988) for biliary SOD and the Modified Milwaukee Biliary Group Classification for pancreatic SOD recognize three biliary, and three pancreatic subtypes respectively.[29] The Rome III consensus statement has modified these criteria to some extent[27]. It removed ERCP contrast drainage as a criterion in biliary SOD because of the invasive nature of this test. The revised classification uses ultrasound, non-invasive method, to evaluate the common bile duct diameter.

A new classification system for SOD was proposed by Gong et al in 2011, which claims to better explain the clinical symptoms of SOD from the anatomical perspective and guide clinical treatment of this disease.[30]It is a single center study which needs to be further evaluated before considering it as a standard.

Investigations

In the presence of clinical diagnostic criteria of SOD we need to rule out more common upper gastrointestinal conditions like peptic ulcer disease, GERD, mass/stones obstructing the biliary system and causes of post-cholecystectomy syndrome. Serum liver function tests, amylase and lipase levels should be measured during episodes of pain, if possible. Mild abnormalities (<2 times normal) are frequently found in SOD whereas higher elevations are more common in organic obstruction of the biliary system or liver parenchymal disease. These liver function tests have low specificity and sensitivity for the diagnosis of SOD but it has been shown that abnormal values in type II biliary SOD may favour response to sphincterotomy.[31]Ultrasound and CT scans may show dilated ducts and help to rule out other causes.

Non- invasive diagnostic tests

Due to the invasive nature and difficulties associated with SO manometry (gold standard for SOD) many non-invasive tests have been developed.

1. Morphine–prostigmin provocative test (Nardi test) : Provocation with injection Morphine and neostigmine leads to reproduction of symptoms of SOD and/or fourfold elevation of serum liver/pancreatic enzymes. It’s no longer in use due to its low sensitivity and specificity[32].

2. Functional assessment of gallbladder (gallbladder motility) by transabdominal real-time ultrasonogram: Inappropriate emptying of gallbladder can result from either impaired gallbladder contractions or increased resistance of the sphincter of Oddi due to an elevated basal tone. A detailed work up to exclude secondary causes of impaired gallbladder motility should be done.

A transabdominal real-time ultrasonogram measures gallbladder volume and obtains serial measurements during fasting, after a meal or after an intravenous infusion of CCK analogues. It also allows for assessment of residual volume after emptying and the rate of refilling. However the technique is observer dependent and therefore, its diagnostic role in the assessment of gallbladder emptying has not become the criterion standard in gallbladder dysfunction. Although a low inherent value of measurement of gallbladder motility has been suggested by Lanzini et al (1987),[33]arecent study conducted by Verma et al (2013) suggested the utility of real-time ultrasonogram in selecting patients with poor contractile (<40%) gallbladder for cholecystectomy.[34] Kalloo et al suggested that gallbladder ejection fraction cannot be used to diagnose sphincter of Oddi dysfunction before cholecystectomy since study had a sensitivity of 33%, a specificity of 63%, and a positive predictive value of 25% and regression analysis revealed a poor correlation between sphincter pressure and gallbladder ejection fraction[35].

3. Functional assessment of gallbladder by cholescintigraphy: Cholescintigraphy is performed after administration of technetium 99m–labelled iminodiacetic acid analogues which have a high affinity for hepatic uptake, are readily excreted into the biliary tract and are concentrated in the gallbladder. The net activity-to-time curve for the gallbladder is then derived from subsequent serial observations following either CCK administration or ingestion of a fatty meal. The result is usually expressed as gallbladder ejection fraction, which is the percentage change in net gallbladder counts after the cholecystokinetic stimulus. A low gallbladder ejection fraction has been considered evidence in favour of impaired gallbladder motor function, which can identify patients with primary gallbladder dysfunction in the absence of gallstones. Two systematic reviews, which did not discriminate between slow and rapid intravenous infusion of CCK have concluded that there is no sufficient evidence to recommend the use of CCK cholescintigraphy to select patients for cholecystectomy[36-37].Further research is needed to assign predictive value of CCK cholescintigraphy to recommend cholecystectomy in patients with gallbladder motility dysfunction. Szepes et al (2013) concluded that cholecystokinin-induced gallbladder ejection fraction with nitroglycerin pre-treatment, measured with ultrasonography can be useful in selecting a subgroup of patients who can benefit from sphincterotomy[38], while Ruffolo et al found no statistically significant difference when comparing normal and elevated sphincter pressure with decreased ejection fraction[8].

4. Ultrasonographic assessment of common bile duct and main pancreatic duct diameter after secretory stimulation: Ingestion of a lipid rich meal or secretin administration leads to reproduction of SOD picture which can be observed by USG. Studies comparing this test with SOM have found only modest correlation[39]. Advantages of this test are that it is inexpensive, reproducible and reliable. On the other hand it is time consuming (60-90minutes) and there is poor visualisation of the main pancreatic duct (55-90%)[40]. 5. Endoscopic ultrasonography-secretin test (EUS-S): Serialmeasurement of the main PD diameter using endoscopic USG before and after secretin infusion is done. It is more useful in pancreatic SOD and provides accurate morphological information related to pancreatic pathology but is relatively invasive, expensive and operator dependent[41].

6. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography after secretin stimulation: MRCP is a better investigative tool than diagnostic ERCP due its non-invasive nature. When used along with IV secretin, better delineation of PD and CBD has been reported[42]. But studies, with contradictory conclusions regarding its diagnostic value in SOD, have raised questions regarding the usefulness of this test[43].

7. Quantitative hepatobiliary scintigraphy (HBS): It is performed after i.v. administration of [99Tcm]-diethyl iminodiacetic acid or a similar compound and measures the time of the radio nucleotide excreted from the liver and the biliary tract. Although an attractive alternative to manometry due to its non-invasive nature, studies[44-45] of HBS have been limited by the lack of a standardized protocol and the use of a variety of outcome measures [duodenal appearance time (DAT) >20minutes, hepatic hilum-toduodenum transit time (HDTT)> 10 minutes, or a composite scintigraphic score.

8. Combined stimulated US and HBS: In two studies, combined US after a lipid-rich meal and HBS increased the sensitivity of each modality on its own in the diagnosis of SOD. However, both techniques were less sensitive in the diagnosis of patients with SOD Types II and III. Sgouros and Pereira in 2006 published a systematic review of non-invasive diagnostic methods for SOD and concluded that, non-invasive diagnostic methods for SOD are limited by their low sensitivity and specificity[46].

Morphine-provoked HBS and ss-MRCP appear to be the most promising modalities, with the latter particularly useful in excluding potential structural abnormalities.

Invasive diagnostic tests

This invasive method should be reserved for patients with clinically significant or disabling symptoms or when sphincter ablation is planned for abnormal sphincter function.

1. Endoscopy: It is used to evaluate papilla and periampullary area and biopsy can be taken in suspicious cases.

2. Cholangiography: It helps in ruling out organic obstructive causes of biliary system and contrast drainage time can be measured47. Incomplete emptying of contrast media at45minutes is generally considered abnormal.

3. Pancreatography: It can measure PD diameter and contrast drainage time,9 minutes in the prone position, which may give indirect evidence of SOD.

4. Intraductal ultrasonography(IDUS): The SO appears as a thin hypoechoic circular structure. Limited studies have been done on this modality, which reveal no correlation of thickness with SO basal pressure.[48]

5. Sphincter of Oddi manometry(SOM): It is the gold standard for diagnosis of SOD.[49] It is the only method used to measure the SO motor activity directly. SOM can be performed percutaneously and intraoperatively but it is most commonly done in the setting of ERCP.

Drugs affecting SO activity should be avoided for at least 12hours before SOM. Benzodiazepines do not affect SO and thus are acceptable sedatives used before performing SOM.

Five French, triple lumen catheters are commonly used. Catheters, with long intraductal tips help secure the catheter in the bile duct but it becomes a hindrance for pancreatic manometry. Monorail catheters are catheters with a guidewire, which facilitate cannulation but guidewire have been shown to increase basal sphincter pressure by 50-100%. Perfusate commonly used is distilled water @0.25ml/channel. A new water perfused sleeve system, similar to that used in lower esophageal sphincter, awaits more definitive trial.[50] Both, CBD and PD should be selectively cannulated and studied separately as abnormality may be confined to one or both sphincters.[51] The duct entered can be identified by aspirating the fluid from it: golden yellow indicates bile duct whilst clear fluid indicates pancreatic duct.

Interpretation of SO tracing has relatively uniform criteria with few inter-center variations like required duration of basal SO pressure elevation, number of leads in which basal pressure elevation is required and role of taking an average from the pressure recordings of the three recording ports. Most recommended indicator for the pathology of the SO is basal sphincter pressure but Kalloo and colleagues suggested that intraductal pressure, which is easier to measure than SO pressure, correlates with SO basal pressure.[52] The best study that established the normal cut off values for SOM was reported by Guelrud and associates:

— Basal sphincter pressure < 35 mm Hg

— Intraductal pressure < 13 mm Hg

— Phasic waves

o Amplitude <220 mmHg

o Duration <8 seconds

o Frequency < 10 /min

Patients with SO stenosis have an abnormally elevated basal pressure (>40 mmHg) which is reproducible and unaltered by smooth muscle relaxants. Patients with SO dyskinesia also show elevated basal pressure but it is not reproducible and decreases following administration of smooth muscle relaxants. Other finding are increased frequency (>7/min), >50% retrograde contractions and paradoxical elevation of SO pressure following CCK-8 injection.

SOM study is limited by an increased risk of complications like pancreatitis(30%), which is the most common and most dreaded complication.[53-54] Rolny and associates have found that patients with chronic pancreatitis were at an increased risk for post SOM pancreatitis.[53] Many ways have been recommended to reduce complications like use of aspiration catheter, gravity drainage of the PD after SOM, decrease the perfusion rates to < 0.05-0.1 mL/lumen/min, limiting the PD manometry time to less than 2minutes, use of micro transducer (non–perfused) system, and placement of pancreatic stent following procedure.[55] Therefore, SOM is recommended in patients with idiopathic pancreatitis or unexplained disabling pancreaticobiliary pain with or without hepatic enzyme abnormalities.

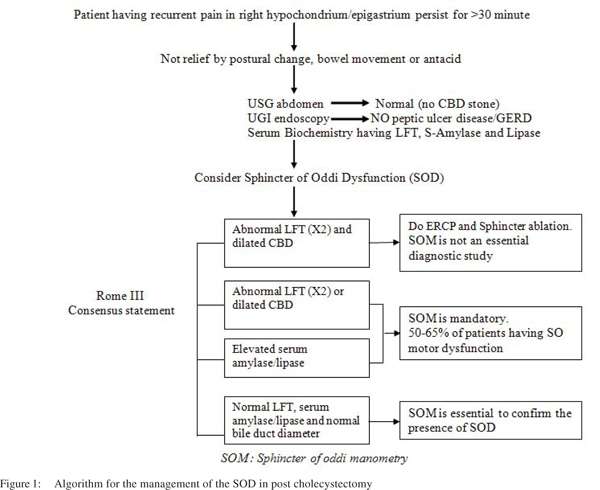

In type I patients SOM is not an essential diagnosis study prior to endoscopic or surgical sphincter ablation due to presence of structural disorder of the sphincter.

In type II patients SOM is highly recommended because of so motor dysfunction (50-65%).

In type III patients SOM is mandatory to confirm the presence of SOD because of absence of objective evidence of sphincter outflow obstruction and only presence of pancreaticobiliary pain.

Treatment

The ultimate aim of the therapeutic interventions is to relieve the obstruction to outflow of bile and pancreatic juice. This can be achieved by medical, surgical or endoscopic approach.

Medical

This approach has undergone only limited research. The SO, being a smooth muscle structure, can be theoretically treated by smooth muscle relaxants. Nitrates (sublingual nitroglycerine) and nifidipine have been used to reduce basal sphincter pressure56. But many drawbacks exist e.g. tachyphylaxis, cardiac and other side effects, nonresponsiveness in structural stenosis, incomplete response in primary motor abnormality of SO. But, because of the relative safety of this modality and benign nature of SOD, this approach can be considered in all Type III and less severely symptomatic Type II SOD patients as an initial approach.

Electrical nerve stimulation

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation has been shown to reduce the basal sphincter pressure but unfortunately, generally not all the way to the normal range[57]. Electro acupuncture applied at acupoint gallbladder 34 results in relaxation of SO along with increase of plasma CCK levels but its role in the management of SOD has not been investigated[58].

Surgical

The most effective therapy is division of SO which leads to amelioration of symptoms and drainage of bile/pancreatic juices.[59] The traditional curative surgical procedure was transduodenal sphincteroplasty, which is also the most commonly used till now.[60] Transampullary septoplasty may be performed along with it. 1-10 year follow up has suggested positive results in 60-70% cases. Patients with elevated basal pressure are more likely to benefit.[61] Some reports suggest better outcome in biliary pain as compared to pancreatic SOD but other reports suggest no such difference[62].

Advantages over endoscopic approach are better efficiency due to easy access and lower rate of re-stenosis. The disadvantages include the invasiveness, increased morbidity, mortality, cost of care, lower patient tolerance and poor cosmesis as compared to endoscopic treatment. At present surgery is recommended only for re-stenosis or when endoscopic therapy is not available or feasible.

Endoscopic

Endoscopic sphincterotomy is the current standard of therapy for SOD. Positive results have been found in 55-95% of patients.[63-64] This variability in outcome is due to the different definitions of SOD used, degree of obstruction, methods of data collection and pain relief measurement. Addition of pancreatic sphincterotomy has been shown to augment the outcome[65].Patients undergoing endoscopic sphincterotomy for SOD have two to five times higher rate of complications as compared to choledocholithiasis patients undergoing the same procedure.[66]Pancreatitis (30%) is the most common complication. SOD, itself has proven to be a risk factor toward post-ERCP pancreatitis[67].

Endoscopic botulinum toxin injection into the SO results in reduction of basal sphincter pressure by 50% and symptomatic improvement but further studies are warranted before recommending this technique.[68]Endoscopic balloon dilatation and biliary stenting was tried but abandoned due to unacceptably high complication rates.[69]

Diagnostic workup in patients with suspected functional biliary SO disorder in post cholecystectomy patient:

Investigations for SO dysfunction causing biliary-type pain begins with liver function test and tests for pancreatic enzymes, in addition to careful elimination of potential structural abnormalities of the biliary and gastrointestinal tract. This includes transabdominal ultrasonogram, computed tomography scan, endoscopic ultrasonogram, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatogram (MRCP), and ERCP, depending on the resources available. The most practical diagnostic sequence might comprisea liver function test followed by pancreatic enzymes, abdominal ultrasonogram, UGI Endoscopy, MRCP, and then ERCP with SO manometry as needed (Figure 1).

Diagnostic workup in patients with gallbladder in situ and functional biliary SOD

The diagnostic workup of patients with gall bladder in situ should ideally first exclude the presence of a gall bladder dysfunction (Figure 2). Choudhry et al (1993) observed that a combination of endoscopic sphincterotomy, selective cholecystectomy and minimal medical treatment resulted in 68% response rate in patients of SO dysfunction with intact gallbladders.[70]According to Behar et al (2006) the two principal indications for sphincterotomy are biliary pain in subjects with normal gallbladder ejection fraction and idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis.[27]

Conclusion

Presently, our understanding of the pathophysiology and the method of diagnosis is evolving. Not a single non-invasive method is diagnostic. Sphincter of Oddi manometry (SOM) is the gold standard method for evaluating patients with sphincter dysfunction. Since it is an invasive method, good ERCP skills are required, as these patients have relatively higher complication rates (pancreatitis 30%). In types III and II patients with mild to moderate symptoms (pain), medical therapy should be started. Type I, II and III patients with abnormal manometry, should undergo sphincter ablation. The symptomatic relief rate varies from 55% to 95%, so risk-benefit ratio should be evaluated with each patient. Non responders require thorough pancreatic sphincter and pancreatic parenchymal evaluation.

References

- Corazziari E, Shaffer EA, Hogan W, Sherman S, Toouli J. Functional disorders of the biliary tract and pancreas. Gut. 1999;45:48–54.

- Elmunzer BJ, Elta GH. Biliary tract motor function and dysfunction. In: Sleisenger & Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2010;1067–73.

- Sherman S, Lehman GA. Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction: Diagnosis and Treatment. JOP. 2001;2:382–400.

- Hermann RE. The spectrum of biliary stone disease. Am J Surg, 1989;158:171–3.

- Cotton Peter B. Sphincter of Oddi Dysfunction. Medscape Gastroenterology. [Online] 9 July 2009.

- Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, Temple RD, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, et al. U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:1569–80.

- Guelrud M, Mendoza S, Mujica V, Uzcategui A. Sphincter of Oddi (SO) motor function in patients with symptomatic gallstones. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:A361

- Ruffolo TA, Sherman S, Lehman GA, Hawes RH. Gallbladde rejection fraction and its relationship to sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39:289–92.

- Black NA, Thompson E, Sanderson CFB. Symptoms and health status before and six weeks after open cholecystectomy: a European cohort study. ECHSS Group. European Collaborative Health Services Study Group. Gut. 1994;35:1301–5.

- Eversman D, Fogel EL, Rusche M, Sherman S, Lehman GA. Frequency of abnormal pancreatic and biliary sphincter manometry compared with clinical suspicion of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;50:637–41.

- Aymerich RR, Prakash C, Aliperti, G. Sphincter of Oddi manometry: is it necessary to measure both biliary and pancreatic sphincter pressure? Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:183–6.

- Geenen JE, Nash JA. The role of sphincter of Oddi manometry and biliary microscopy in evaluating idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 1998;30:A237–41.

- Loukas M1, Spentzouris G, Tubbs RS, Kapos T, Curry B. Ruggero Ferdinando Antonio Guiseppe Vincenzo Oddi. World J Surg. 2007;31:2260–5.

- Boyden EA. The anatomy of the choledochoduodenal junction in man. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1957;104:641–52.

- Geenen JE, Hogan WH, Dodds WJ, Stewart ET, Arndorfer RC. Intraluminal pressure recording from human sphincter of Oddi. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:317–24.

- Worthley CS, Baker RA, Saccone GTP, McGEE M, Toouli J. Interdigestive and post-prandial contractile activity of the human sphincter of Oddi. Aust NZ J Med. 1987;17:502.

- Guelrud M, Mendoza S, Rossiter G. Sphincter of Oddi manometry in healthy volunteers. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35:38–46.

- Toouli J, Hogan WJ, Geenen JE, Dodds WJ, Arndorfer RC. Action of cholecystokinin-octapeptide on sphincter of Oddi basal pressure and phasic wave activity in humans. Surgery.1982;92:497–503.

- Staritz M. Pharmacology of the sphincter of Oddi. Endoscopy. 1988;20:171–4.

- Richards RD, Yeaton P, Shaffer HA Jr, Pambianco DJ, Pruett TL, Stevenson WC, et al. Human sphincter of Oddi motility and cholecystokinin response following liver transplantation. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:462–8.

- Chuttani R, Carr-Locke DL. Pathophysiology of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Surg Clin N Am. 1993;73:1311–22.

- Quallich LG, Stern MA, Rich M, Chey WD, Barnett JL, Elta GH. Bile duct crystals do not contribute to sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:163–6.

- Tanaka M. Advances in research and clinical practice in motor disorders of the sphincter of Oddi. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2002;9:564–8.

- Abraham HD, Anderson C, Lee D. Somatization disorder in sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Psychosom Med. 1997;59:553–7.

- Appendix A :Rome III Diagnostic Criteria for FGIDs. In: Rome III: The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Third Edition. MacLean, VA: Degnon Associates Inc.2006. p.891.

- Bistritz L, Bain VG. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: Managing the patient with chronic biliary pain. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3793–802.

- Behar J, Corazziari E, Guelrud M, Hogan W, Sherman S, Toouli J. Functional Gallbladder and Sphincter of Oddi disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1498–509.

- Tarnasky PR, Palesch YY, Cunningham JT, Mauldin PD, Cotton PB, Hawes RH. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1518–24.

- Brandstatter G, Schinzel S, Wurzer H. Influence of spasmolytic analgesics on motility of sphincter of Oddi. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:1814–8.

- Gong JQ, Ren JD, Tian FZ, Jiang R, Tang L J, Pang Y. Management of patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction based on a new classification. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:273–408.

- Lin OS, Soetikno RM, Young HS. The utility of liver function test abnormalities concomitant with biliary symptoms in predicting a favorable response to endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with presumed sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1833–6.

- Steinberg WM, Salvato RF, Toskes PP. The morphine-prostigmin provocative test: is it useful for making clinical decisions? Gastroenterology. 1980;78:728–31.

- Lanzini A, Jazrawi RP, Northfield TC. Simultaneous quantitative measurements of absolute gallbladder storage and emptying during fasting and eating in humans. Gastroenterology. 1987;92:852–61.

- Verma A, Bhartiya SK, Basu SP, Shukla RC, Shukla VK. Gallbladder motility study evaluation of asymptomatic gallbladder stones. Indian Journal of Applied Research. 2013;3:1–4.

- Kalloo AN, Sostre S, Meyerrose GE, Pasricha PJ, Szabo Z. Gallbladder ejection fraction. Nondiagnostic for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction in patients with intact gallbladders. Clin Nucl Med. 1994;19:713–9.

- Delgado-Aros S, Cremonin F, Bredemoord AJ, Camilleri M.Systematic review and meta-analysis: does gallbladder ejection fraction on cholecystokinin cholescintigraphy predict outcome after cholecystectomy in suspected functional biliary pain? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:167–74.

- Di Baise JK, Olejnikov D. Does gallbladder ejection fraction predict outcome after cholecystectomy for suspected chronic a calcolous gallbladder dysfunction? A systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2605–11.

- Szepes A, Dubravcsik Z, Madácsy L. The effect of endoscopic sphincterotomy on the motility of the gallbladder and of the sphincter of Oddi in patients with acalculous biliary pain syndrome. Orv Hetil. 2013;154:306–13.

- Rosenblatt ML, Catalano MF, Alcocer E, Geenen JE. Comparison of sphincter of Oddi manometry, fatty meal sonography and hepatobiliary scintigraphy in the diagnosis of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:697–704.

- Hadidi A. Pancreatic duct diameter: sonographic measurement in normal subjects. J Clin Ultrasound. 1983;11:17–22.

- Catalano MF, Lahoti S, Alcocer E, Geenen JE, Hogan WJ. Dynamic imaging of the pancreas using real-time endoscopic ultrasonography with secretin stimulation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:580–7.

- Czako L, Takacs T, Morvay Z, Csernay L, Lonovics J. Diagnostic role of secretin- enhanced MRCP in patients with unsuccessful ERCP. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;15:3034–8.

- Mariani A, Curioni S, Zanello A, et al. Secretin MRCP and endoscopic pancreatic manometry in the evaluation of sphincter of Oddi function: a comparative pilot study in patients with idiopathic recurrent pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:847–52.

- Pineau BC, Knapple WL, Spicer KM, Gordon L, Wallace M, Hennessy WS,et al. Cholecystokinin stimulated mebrofinin (99mTc-Choletec) hepatobiliary scintigraphy in asymptomatic postcholecystectomy individuals: assessment of specificity interobserver reliability and reproducibility. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;97:3106–9.

- Craig AG, Peter D, Saccone GT, ZiesingP, WycherleyA, Toouli J. Scintigraphy versus manometry in patients with suggested biliary sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gut. 2003;52:352–7.

- Sgouros SN, Pereira SP. Systematic review: sphincter of Oddi dysfunction – non-invasive diagnostic methods and long-term outcome after endoscopic sphincterotomy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:237–46.

- Elta GH, Barnett JL, Ellis JH, Ackermann R, Wahl, R. Delayed biliary drainage is common in asymptomatic postcholecystectomy volunteers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:435–9.

- Wehrmann T, Stergiou N, Riphaus A Lembcke B. Correlation between sphincter of Oddi manometry and intraductal ultrasound morphology in patients with suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Endoscopy. 2001;33:773–7.

- Lans JL, Parikh NP, Geenen, JE. Application of sphincter of Oddi manometry in routine clinical investigations. Endoscopy. 1991;23:139–43.

- Craig AG, Omari T, Lingenfelser T, Schloithe AC, Saccone GT, Dent J et al. Development of a sleeve sensor for measurement of sphincter of Oddi motility. End scopy. 2001;33:651–7.

- Chan YK, Evans PR, Dowsett JF, Kellow JE, Badcock, CA.Discordance of pressure recordings from biliary and pancreatic duct segments in patients with suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42:1501–6.

- Kalloo AN, Tietjen TG, Pasricha PJ. Does intrabiliary pressure predict basal sphincter of Oddi pressure? A study in patients with and without Gallbladder s. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:696–9.

- Rolny P, Anderberg B, Ihse I, Lindstrom E, Olaison G, Arvill A. Pancreatitis after sphincter of Oddi manometry. Gut. 1990;31:821–4.

- Maldonado ME, Brady PG, Mamel JJ, Robinson B. Incidence of pancreatitis in patients undergoing sphincter of Oddi manometry (SOM). Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:387–90.

- Tarnasky PR, Palesch YY, Cunningham JT, Mauldin PD, Cotton PB, Hawes RH. Pancreatic stenting prevents pancreatitis after biliary sphincterotomy in patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:1518–24.

- Guelrud M, Mendoza S, Rossiter G, Ramirez L, Barkin J. Effect of nifedipine on sphincter of Oddi motor activity: studies in healthy volunteers and patients with biliary dyskinesia. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:1050–5.

- Guelrud M, Rossiter A, Souney P, Mendoza S, Mujica V. The effect of transcutaneous nerve stimulation on sphincter of Oddi pressure in patients with biliary dyskinesia. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:581–5.

- Lee SK, Kim MH, Kim HJ, Seo DS, Yoo KS, Joo YH, et al. Electro acupuncture may relax the sphincter of Oddi in humans. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:211–6.

- Elton E, Howell DA, Parsons WG, Qaseem T, Hanson BL. Endoscopic pancreatic sphincterotomy: indications, outcome and a safe stentless technique. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:240–9.

- Toouli J, Francesco V, Saccone G, Kollias J, Shanks N. Division of the sphincter of Oddi treatment of dysfunction associated with recurrent pancreatitis. Br J Surg. 1996;83:1205–10.

- Sherman S, Hawes RH, Madura J, Lehman GA. Comparison of intraoperative and endoscopic manometry of the sphincter of Oddi. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1992;175:410–8.

- Moody FG, Vecchio R, Calabuig R, Runkel N. Transduodenal sphincteroplasty with transampullary septectomy for stenosing papillitis. Am J Surgery. 1991;161:213–8

- Rolny P, Geenen, JE, Hogan WJ. Post-cholecystectomy patients with ‘objective signs’ of partial bile outflow obstruction: clinical characteristics, sphincter of Oddi manometry findings, and results of therapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:778–81.

- Toouli, J, Roberts-Thomson IC, Kellow J, Dowsett J, Saccone GTP, Evans P et al. Manometry based randomized trial of endoscopic sphincterotomy for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gut. 2000;46:98–102.

- Guelrud M, Plaz J, Mendoza S, Beker B, Rojas O, Rossiter G.Endoscopic treatment in Type II pancreatic sphincter dysfunction. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995;41:A398.

- Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy: a prospective, multicenter study. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909–18.

- Freeman ML, DiSario JA, Nelson DB, Fennerty MB, Lee JG, Bjorkman DJ, et al. Risk factors for post-ERCP pancreatitis: a prospective, multicenter study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:425–34.

- Pasricha, PJ, Miskovsky EP, Kalloo AN. Intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin for suspected sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. Gut. 1994;35:1319–21.

- Kozarek, RA. Balloon dilation of the sphincter of Oddi. Endoscopy. 1988;20:207–10.

- Choudhry U, Ruffolo T, Jamidar P, Hawes R, Lehman G. Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction in patients with intact gallbladder: therapeutic response to endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1993;39:492–5.

|

|

|

|

|

|