48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|1827

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Intramural esophageal hematoma is an uncommon esophageal injury, which can present as a rare cause of upper gastro-intestinal hemorrhage. It has also been mentioned as an unusual cause of acute chest pain.1Esophageal hematomas usually occur secondary to trauma, therapeutic interventions or disorders of hemostasis, and rarely can occur spontaneously. Sudden changes in esophageal pressure as occur during uncoordinated movements while swallowing, or vomiting have also been described as etiological factors.2

Case Report

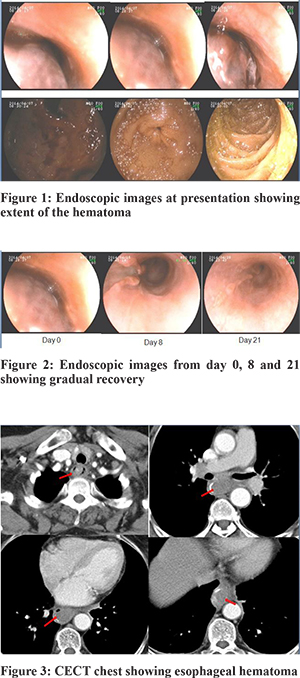

A 72 year old lady presented with recurrent retching and vomiting, retrosternal chest pain and pain epigastrium with dysphagia of two hour duration. She had two episodes of hematemesis in the emergency department. The patient gave history of Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypothyroidism and coronary artery disease for which she was on dual anti platelet therapy. Clinical evaluation revealed an anxious patient with tachycardia, tachypnea and blood pressure of 180/84 mm Hg. Systemic examination was within normal limits. Blood reports were sent and her hemogram revealed mild anemia (Hb – 10.8 gm/dL). Other investigations including liver and renal function tests, coagulogram, ECG, chest X–ray and ultrasound abdomen did not reveal any abnormality. A presumptive diagnosis of Mallory Weiss tear was made and she was taken up for upper GI endoscopy on the same day. The endoscopy revealed a large submucosal esophageal hematoma extending from mid esophagus (approx 25 cm) to just above the esophago-gastric junction (40 cm) (Figure 1 & Figure 2). A computed tomography(CT) scan of chest was ordered to confirm the extent of hematoma and to look for wall integrity. It revealed a lesion occupying most of the lumen of esophagus, and extending from the mid esophagus to just above the esophago-gastric junction (Figure 3). Based on the endoscopic & Chest CT scan findings, patient was diagnosed as a case of spontaneous esophageal submucosal hematoma.

Patient was admitted and managed conservatively with fasting, anti-emetics, and sucralfate. Her anti–platelet medications were withheld, and antihypertensive drugs and thyroxine were continued. Retching and vomiting improved by day 2 of admission and there was no recurrence of hematemesis. Oral clear fluids were introduced on day 4, and soft diet was started on day 6 of hospital stay. Repeat UGIE was done on day 8 and it revealed a complete resolution with a large mucosal tear from 30 – 36 cm. Patient was discharged on day 11. At the time of discharge, she did not have complain of odynophagia or dysphagia, was tolerating normal oral feeds and her hemoglobin level was 11.0 gm/dL. She underwent a third UGIE on day 21, which revealed complete healing of the mucosal tear. (Figure 2)

Discussion

Esophageal injuries have been known since the 18th century when Hermann Boerhaave described the Boerhaave’s syndrome in 1724. With further recognition of esophageal injuries, it came to be known that esophageal injuries are of three major types – Boerhaave’s syndrome which is a full thickness rupture of the esophagus, Mallory Weiss tear which represents a mucosal tear, and intramural dissection leading to esophageal hematoma. Of these three, esophageal hematoma is the least common and most of the literature comes from case reports. Kerr reported a case series of five patients and also a review of 15 other patients in 1980.3 He reported that chest pain was the presenting symptom in all patients, while hematemesis was seen in only 14 patients (70 percent), and dysphagia was present in 11 patients (55 percent). In another case report by Chu et al, it was reported that retrosternal chest pain, dysphagia, and hematemesis form the triad of esophageal hematoma, and that 35 percent of patients present with the complete triad and half of the patients with at least two symptoms.4 More recently, Shim et al reviewed 119 patients presenting with esophageal hematoma and found that major bleeds (defined as more than 500 mL hematemesis with hypovolemic shock or bleeding that required transfusion of at least 4 units) occurred in eleven patients (9.2 percent).5

Diagnosis is usually made by direct visualization on endoscopy or by CT scan of the chest. Endoscopy can be performed safely in patients who present with hematemesis,6 and it is important to diagnose patients presenting with acute chest pain as inadvertent anticoagulation or anti platelet therapy may increase chances of enlarging hematoma formation, esophageal compression, and potentially life-threatening rupture.

Management is usually conservative, and includes measures such as withholding of oral feeds during acute phase with gradual re-initiation as symptoms resolve, cessation of drugs which can prolong bleeding, and anti–emetics for retching and vomiting. Surgery is usually reserved for cases with either massive bleeding or perforation. Shim et al reported treatment of a case with therapeutic angiography.5 Most cases have favorable outcomes, with progressive resolution of lesion, which usually ulcerates before resolving.

References

- Kerr WF. Spontaneous intramural rupture and intramural haematoma of the oesophagus. Thorax 1980; 35:890-7

- Abbey P, Sharma R, Garg P K. Spontaneous intramural haematoma of the oesophagus: complete resolution on follow-up magnetic resonance imaging. Singapore Med J 2009; 50(9): e318-e20

- Kerr WF. Spontaneous intramural rupture and intramural haematoma of the oesophagus. Thorax 1980; 35: 890-897

- Lu MS, Liu YH, Liu HP, Wu YC, Chu Y, Chu JJ. Spontaneous intramural esophageal hematoma. Ann Thorac Surg 2004;78(1): 343-5

- Shim J, Jang JY, Hwangbo Y, Dong SH, Oh JH, Kim HJ et al.Recurrent massive bleeding due to dissecting intramural hematoma of the esophagus: Treatment with therapeutic angiography. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(41): 5232-5

- McIntyre AS, Ayres R, Atherton J, Spiller RC, Cockel R. Dissecting intramural haematoma of the oesophagus. Q J Med 1998;91:701