48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|1938

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Capillaria hepatica (C. hepatica) is a nematode belonging to the family Trichocephalidea and class Trichuroidea1. First described by Bancroft in 18932, it infects primarily rodents; how ever it can affect over 140 mammalian species, including humans3. C. hepatica has a global distribution but the prevalence of human infection is extremely low with less than 75 cases of true infection being reported worldwide3. The most common symptoms include fever, hepatomegaly and eosinophilia thereby having a number of clinical differential diagnoses.

Children in developing countries belonging to a low socio-economic background are particularly vulnerable to developing infection with C. hepatica due to substandard hygienic conditions. A heavy parasitic load can lead to increased morbidity and even mortality due to hepatic failure. A timely liver biopsy and diagnosis by histopathology can be life saving. We report the second case of C. hepatica from North India in a paediatric patient diagnosed with the help of liver biopsy.

Case Report

An eighteen month old girl, resident of Dumri village, Bihar, India, presented with high grade fever and abdominal distension for two months. There was progressive loss of weight and appetite from the onset of the illness. At that time, the patient received ayurvedic medication from a local village doctor for two weeks.There was no history of pain abdomen, vomiting, yellowish discoloration of the eyes, high-coloured urine or passage of worms in stool. On examination, she had a temperature of 103° F and severe pallor. The abdomen was soft with palpable liver and spleen, 8 cm and 2 cm below the right and left costal margins, respectively.

Laboratory investigations revealed severe microcytic hypochromic anaemia (haemoglobin of 6 g/dl), leucocytosis (26.7 X 109/L) with 33% eosinophils (absolute eosinophil count (AEC) was 8.8 X 109/L).The patient’s erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was raised (45 mm/h). Liver function tests were normal. A bone marrow examination showed erythroid hyperplasia and increase in eosinophilic precursors. Bone marrow and blood cultures were sterile. Chest X-ray and urine and stool microscopy were normal. Malaria and tuberculosis workup, filarial antigen, rK39 antigen and TORCH profile were negative. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) abdomen revealed hepatomegaly with heterogeneous enhancement and periportal low attenuating areas, likely representing periportal fibrosis (Figure 1). The clinical picture was that of febrile hepatosplenomegaly with severe anaemia and eosinophilia. The differentials included parasitic infestation, malignancy and chronic liver disease with drug induced liver injury. A liver biopsy was done to establish the diagnosis.

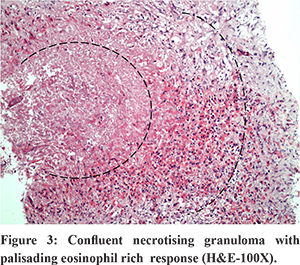

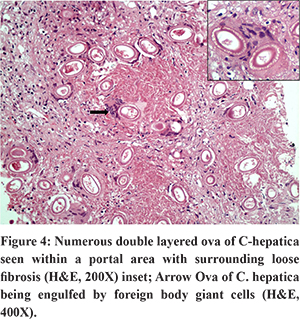

The liver biopsy (Figures 2-4) showed expanded portal tracts with portal and periportal fibrosis. The portal areas showed numerous confluent necrotising granulomas and peripheral eosinophilic and histiocytic response along with fibroblastic rimming. Within the granulomas, numerous spherical to ovoid structures were identified. They showed a double- enveloped wall with fine radial striations between the two layers. Some showed unipolar to bipolar mucous plugs. This distinct morphology confirmed to that of C. hepatica ova. No adult worms were seen. Additionally, an extensive foreign body giant cell response was identified. Eosinophilic microabscesses were noted in the hepatic parenchyma. A final diagnosis of granulomatous hepatitis due to C. hepatica was given.

Following the biopsy report, the patient’s history was reviewed and it was found that the child’s residence was near a granary infested by rats. A history of pica was given by the patient’s mother. She was started on albendazole for 3 months along with oral steroids for 3 weeks. Haematinics and vitamin D supplementation were also started. A month following the diagnosis, the patient was afebrile witha decrease in liver and spleen size and normalization of the AEC.

Discussion

C. hepatica has a direct life cycle, requiring a single host; both adult worms and ova are present in the host liver. These ova are unembryonated and thus, not infective. On death and decay of the organism, they are released into the soil, where they mature within a month to embryonated forms. True infection occurs when the embryonated ova are ingested by humans in contaminated food, water or soil. The larvae hatch in the small intestine and penetrate the portal vein to reach the liver where they form adult worms and copulate. The fertilised female deposits unembryonated eggs in the hepatic parenchyma; which subsequently become enclosed in granulomas. The adult worms die approximately forty to sixty days after infection4. The disintegrating worms release cytokines which induce an eosinophil-rich inflammatory and fibrotic response in the liver.

Spurious infection occurs when a scavenger predates upon theinfected host and unembryonated eggs reach its gut causing transient gastrointestinal symptoms. Over 78 cases of spurious infection (pseudocapillaria)have been reported in humans from South America and China3. Seventy four cases of true infection have been reported worldwide, only six of which are from India (5 from Maharashtra and 1 from Uttar Pradesh). Poor hygienic conditions and the presence of rodents increase the risk of infection. Sixty percent of cases reported are in children less than 8 years of age, the youngest being an 11 month male3. Frequent soil- hand- mouth contact explains the increased susceptibility in children.

The clinical manifestations are variable depending on the parasite load. A diagnosis is difficult to make due to the non-specific symptoms and radiology, non availability of immunologic tests for detection and absence of ova in stools in true infection5. Laboratory tests show leucocytosis, eosiniphilia and elevated liver enzymes. Definite diagnosis is by liver biopsy and identification of C. hepatica ova. The eggs of C. hepatica have to be differentiated from those of Schistosomiamansoni. The smaller size of C. hepatica ova, regular striations, birefringent bi-layered capsule and mucus plugs help clinch the diagnosis5. Schistosoma japoni cumova are of similar size as C. hepatica (60 X 30 µm); however. they possess lateral knobs and an acid fast shell. The eggs of Trichuris trichura (passed in stool) are ovoid and have bipolar plugs but lack a striated envelope.

Hepatic capillariasis is treated with benzimidazoles; steroids maybe given to reduce inflammation3,5. The prognosis depends on the severity of the infestation. Massive necrosis of the liver parenchyma and advanced fibrosis can lead to mortality. Therefore, a picture of tropical eosinophilia syndrome, especially in children should warrant suspicion for C. hepatica infection. A detailed environmental history is vital. Since histopathology is the cornerstone for diagnosis, it is imperative for pathologists to be aware of this rare entity.

References

- Moravec F. Proposal of a new systematic arrangement of nematodes of the Family Capillariidae. Folia Parasitologica. 1982; 29: 119-32.

- Bancroft T.L. On the whip-worm of the rats liver. Journal and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales. 1893; 27: 86-90.

- Fuehrer HP, Igel P, Auer H. Capillaria hepatica in man--an overview of hepatic capillariosis and spurious infections. Parasitol Res. 2011; 109: 969-79.

- KA Wright. Observations on the life cycle of capillaria hepatica (Bancroft, 1893) with a description of the adult. Can J Zool. 1961; 39: 167-82.

- Sawamura R, Fernandes MI, Peres LC, Galvão LC, Goldani HA, Jorge SM. Hepatic capillariasis in children: Report of 3 cases inBrazil. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999;61:642-7.