48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|1931

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Portal hypertension related from gastric varices or ectopic varices may be difficult to control in some cases by endoscopic measures. Interventional radiology (IR) procedures like transhepatic intrahepatic portosystemic shunt or balloon guided retrograde transvenous obliteration are procedures of choice. However, IR procedures require patent venous access and are not possible sometimes due to venous thrombosis. We present a case series of 3 cases with failed endoscopic intervention and non-feasibility of IR procedure. These patients were managed by endoscopic ultrasound guided coil and glue (n=2) or glue alone (n=1), control of bleed could be achieved in all.

Case Report

Case 1

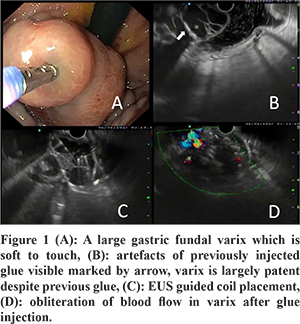

A 55-year-old male, known case of cirrhosis, large hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) with extensive portal vein tumour thrombosis and splenic vein thrombosis presented with melaena. A gastroscopy was done outside which revealed a large gastric varix for which glue injection was done. However, he had an upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleed again after 1 week and was referred to us. Endoscopic examination showed a gastric varix which was soft to touch in all parts. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) showed a large gastric varix with artefacts of the previously injected glue. Despite the endoscopic glue injected earlier, this varix was largely patent. TIPSS was not feasible due to portal vein thrombosis and balloon retrograde transvenous obliteration (BRTO) was not possible due to absence of a spontaneous suitable shunt. Due to the large size of varix, two coils were placed followed by injection of 1 ml glue + 1 ml lipiodol combination. EUS confirmed obliteration of blood flow in the varix at the same time as shown in Figure 1. There was no bleeding episode for the six months that followed after which the patient expired due to hepatocellular carcinoma.

Case 2

A 55-year-old male had hematemesis and melena. He was a known case of portal cavernoma, who had previously undergone a splenectomy for pancytopenia and hypersplenism. An upper GI endoscopy revealed a varix with active bleed in the duodenal blub. The bleed could not be stopped after injection of undiluted glue by endoscopy. Gastro-intestinal surgery and interventional radiologic (IR) guided intervention was not possible due to splenectomy and portal vein thrombosis. He was taken for EUS guided coil and glue injection. EUS revealed a patent vascular channel inside the varix and 1 ml glue was injected. EUS confirmed obliteration of the varix. The patient is doing well at 4 months after the procedure.

Case 3

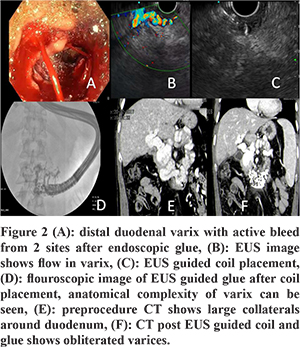

A 33-year-old male, had melena and was diagnosed to have distal duodenal/proximal jejunl varices (Figure 2). Glue was injected under enteroscopy guidance. A computed tomography (CT) abdomen showed extensive and large collaterals around the duodenum and proximal jejunum (Figure 2). He presented again with an upper GI bleed for which enteroscopy-guided glue injection was done, but the patient had active bleed from 2 sites including the site of needle puncture. The endoscopic view got blurred soon due to the active bleed and the decision for EUS-guided coil/glue was discussed with the patient’s family. EUS showed a patent varix. A single coil followed by 1 ml glue and 1 ml lipiodol mixture was injected. Ths led to obliteration of the varix that was visible. Flouroscopy highlighted the complex anatomy of the varix as it retained glue. A CT done following the procedure showed obliteration of the varices as shown in Figure 2. The patient is doing well at 3 months after the procedure.

EUS-guided coil insertion and glue injection technique

The Doppler function of the EUS was used to see the vascular anatomy of the varix after localization. A lot of water was used in the case of fundal varices for better visualisation. The varix was punctured with a 19 G needle after removal of the stylet and preloading the needle with 5% dextrose. The size of the coil was kept 20% larger than the diameter of the varix. The coils were pushed into the varix using a stylet and the procedure was monitored under fluoroscopy. After coil placement, 1 ml glue and 1 ml lipiodol combination was injected through the same FNA needle, under fluoroscopic guidance to monitor for immediate embolisation.

Discussion

Gastric varices and are seen in 5% to 33% of patients with portal hypertension.1-3 Ectopic varices are uncommon. Although they bleed less frequently than oesophageal varices, bleeding due to gastric varices/ectopic varices tends to be more severe with a higher risk of mortality.2,3 In particluar, ectopic varices pose a risk of endoscopic therapy failure if there are large collaterals in vicinity. Tissue adhesives such as N-butyl-cyanoacrylate (CYA) are the endoscopic treatment of choice for IGV1,2 and GOV2. Endoscopic glue is associated with a significant risk of complications such as embolisation, bleeding, ulceration and extrusion.2-4 Also, it is difficult to see varices properly in the presence of an active bleed or a large blood clot or food residue in the fundus by a conventional gastroscope. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) overcomes the limitations of conventional endoscopy. EUS-guided delivery of cyanoacrylate (CYA) glue enables real-time precise delivery of the glue directly into the varix lumen. Moreover, EUS also enables the use of Doppler evaluation to confirm varix obliteration simultaneously. The various EUS-guided therapies used for gastric varices include glue injection, coil placement and combination of both the above. While glue placement carries a risk of embolisation, coils larger than the size of the varix are costly. Thus, a combination of EUS-guided coil and glue decreases the cost (lesser numbers of coils are needed) and reduces the risk of embolisation (lesser amount of glue is needed and the coils act as a scaffold to retain the glue, thereby decreasing the chances of glue embolization). In a retrospective study of 152 patients, EUS-guided combined coil and glue injection of high-risk gastric varices appears to be highly effective for hemostasis in active bleeding and primary and secondary bleeding prophylaxis.5 Once obliteration was achieved, post-treatment bleeding from varices occurred in only 3% of patients during long-term follow-up.5 While asymptomatic glue embolization in the glue-alone group is very common,6 combination therapy appears safe and may reduce the risk of glueembolisation. EUS-guided coil and glue has been shown to be effective in several other studies also.6,7

To summarise, we present a series of 3 cases where endoscopy failed and IR-guided intervention was not possible/feasible. EUS-guided therapy achieved variceal obliteration in all these cases.

References

- Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, et al; Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46:922-38.

- Triantafyllou M, Stanley AJ. Update on gastric varices. World J GastrointestEndosc2014; 6: 168-75

- Cheng LF, Wang ZQ, Li CZ, et al. Treatment of gastric varices by endoscopic sclerotherapy using butyl cyanoacrylate: 10 years’ experience of 635 cases. Chin Med J (Engl) 2007; 120: 2081-5

- Sarasvat VA and Verma A. Gluing Gastric Varices in 2012: Lessons Learnt Over 25 Years. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2012; 2: 55–69

- Bhat YM, Weilert F, Fredrick RT et al. EUS-guided treatment of gastric fundal varices with combined injection of coils and cyanoacrylate glue: a large U.S. experience over 6 years (with video) GastointestEndosc. 2016; 83:1164-72

- Binmoeller KF, Weilert F, Shah JN, Kim J. EUS-guided transesophageal treatment of gastric fundal varices with combined coiling and cyanoacrylate glue injection (with videos). GastrointestEndosc. 2011 ;74:1019-25.

- Romero-Castro R, Ellrichmann M, Ortiz-Moyano C, Subtil-Inigo JC, Junquera-Florez F, Gornals JB et al. EUS-guided coil versus cyanoacrylate therapy for the treatment of gastric varices: a multicenter study (with videos). GastrointestEndosc. 2013;78:711-21.