Chronic mesenteric ischemia (CMI) is an uncommon condition secondary to atherosclerotic disease of the mesenteric arteries. Symptomatic CMI must be revascularized without delay. Surgery and endovascular approaches are the ways through which this could be accomplished.

Case Report

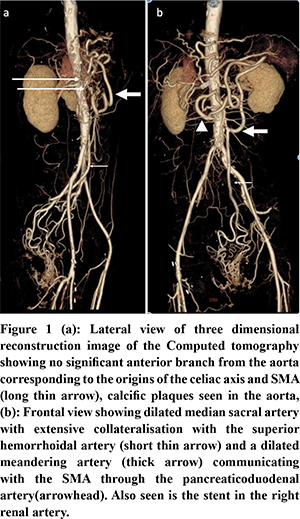

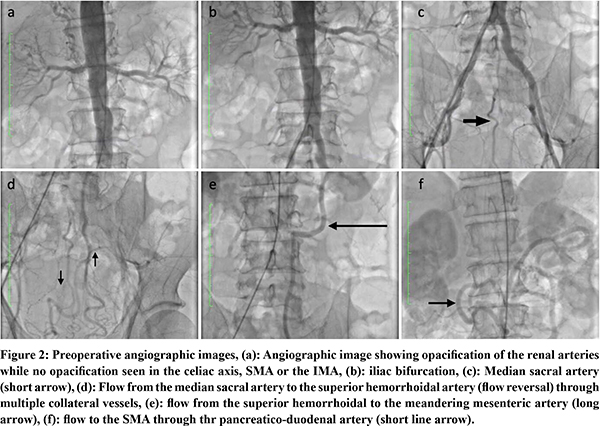

51-year-old gentleman, a known hypertensive and a chronic smoker presented with abdominal angina, food fear, and weight loss for 1 month. He had a past history of coronary angioplasty for coronary artery disease and right femoro-popliteal bypass along with a right renal artery stenting for peripheral vascular disease. On examination, abdomen was scaphoid. He was evaluated with contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen (Figure 1). Arterial phase imaging showed complete occlusion of origins of celiac axis, Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) and an unusual collateral pathway with a large meandering mesenteric artery collateralized through median sacral, superior hemorrhoidal, inferior mesenteric and inferior pancreatico duodenal arteries. The patient was planned for an endovascular procedure. An angiogram done confirmed the above findings with retrograde filling of the SMA through the median sacral, superior hemorrhoidal, meandering mesenteric artery, inferior pancreatico-duodenal route. However, an attempt at SMA stenting failed as SMA cannulation could not be achieved (Figure 2). The patient underwent a retrograde open re-vascularisation of the SMA with a 7 mm polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) graft.

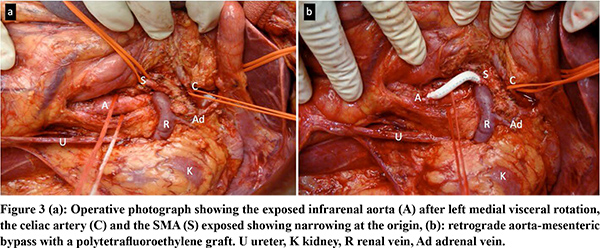

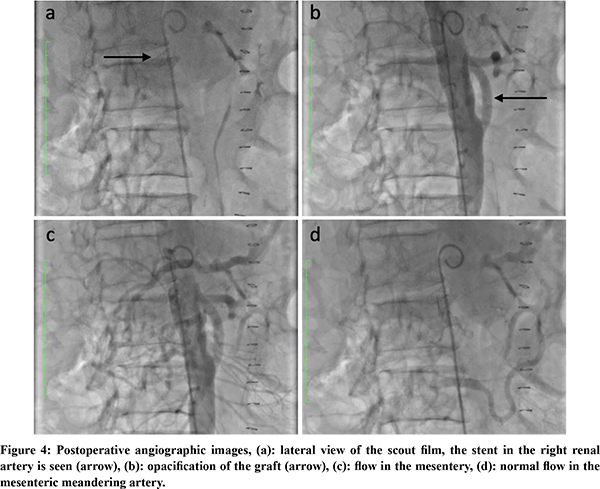

Under general anesthesia, after sterile preparation and draping, the abdomen was opened through a long midline incision and retractors were positioned. A Mattox maneuver (a left medial visceral rotation) was performed. The aorta was exposed from the origin of the celiac artery to its bifurcation, Aorta was diseased with plaque throughout (Figure 3a). There was a plaque at the origin of the coeliac axis. SMA pulsations were absent at the root. Aorta was side clamped and an inflow anastomosis was done (continuous 4-0 polypropylene suture) on the infra renal aorta which was free from the disease using a 7mm PTFE graft. The graft length was cut to 5 cm and edge beveled to fashion and complete the distal landing on the proximal SMA which was free from the disease (Figure 3b). The patient had an uneventful post-operative course. Follow up aortogram showed excellent flow through the graft and reversal of flow through the meandering mesenteric artery (Figure 4). On follow up at 1 year, the patient is pain free and has gained weight.

Discussion

Chronic mesenteric ischemia is an uncommon condition1. There is rich collateralization between the mesenteric vessels. CMI is seen due to mesenteric insufficiency in the post prandial period. In cases where one of the three mesenteric arteries are involved with an atherosclerotic process the blood supply is maintained by the other two. With the involvement of at least two arteries in the atherosclerotic process, mesenteric ischemia ensues. In our case where all three mesenteric arteries were involved in the disease process and the basal need was maintained from the median sacral artery2. The classical symptoms include post prandial abdominal pain, food fear, and unintentional weight loss. In patients who are symptomatic for mesenteric ischemia, restoration of blood supply must be done without delay as more than 40% of symptomatic patients end up with acute mesenteric ischemia3. Patients are often elderly with multiple comorbidities like coronary artery disease, hypertension, renal insufficiency and diabetes like in our patient. Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) is the investigation of choice. It provides three dimensional reconstruction which can assist in surgical planning. Although CT visceral angiogram gives adequate information, a flush aortogram provides more dynamic information regarding collateral flow and is the gold standard. Management options include endovascular procedures and surgery. Stenting is the preferred endovascular procedure as angioplasty is fraught with recurrence of symptoms. With the advent of advanced endovascular techniques and less physiological stress on already compromised patients, endovascular interventions have become the first line of management. Surgery is considered in patients with extensive occlusive disease and where endovascular intervention is not feasible either due to contrast allergy or endovascular failures like in our patient. However the freedom from recurrence of symptoms is higher with surgery and the requirement of re-intervention is more in the endovascular group. The recurrence free survival at 5 years of patients undergoing endovacular interventions is reported to be around 56%.2 The need for reintervention is seen in around one third to half the patients with 3-year stent latency of only 40%.2,4 These have to be clearly conveyed to the patient for him to take an informed decision. Surgical options include re-vascularisation using a graft between the aorta and mesenteric or celiac arteries, endarterectomy and rarely, retrograde SMA stenting and re-vascularisation from thoracic aorta, subclavian, or axillary vessels5-7. Re-vascularisation is the preferred modality, however endarterectomy may be useful when there is contamination (bowel gangrene, perforation) precluding the use of a synthetic graft or extensive disease of the aorta where placement of inflow anastomosis is not possible in a safe manner.

Aorto-mesenteric re-vascularisation could be achieved either by an antegrade or a retrograde approach8,9. Antegrade approach requires dissection of the supra celiac aorta for inflow and a retropancreatic tunnel for the distal landing whereas the simpler retrograde approach is from infrarenal aorta or the iliac vessels to the proximal SMA. The proponents of the antegrade approach contend that the approach has had lesser re-intervention as placement is more physiological in contrast to the ‘C’ loop of the graft required in the retrograde approach which increases the risk of kinking whereas those supporting the retrograde approach argue that the clamping of the iliac or the infra renal aorta leads to less hemodynamic stress than supra celiac aorta in a patient who has a poor physiological reserve. Moreover the dissection to expose the infrarenal aorta is simple and less time consuming. There is recent evidence to suggest that retrograde approach is equivalent to antegrade approach and is preferred by some groups over the antegrade8. Another debate is the whether the anastomosis is done to two vessels or a single vessel. The traditional point of view has been that when a second anastomosis is possible without any added morbidity to the patient, it should be added. However, recent reports have showed equivalent results with just a single anastomosis9.

Technical success rate is close to 100% with clinical improvement in over 90%. Long term freedom from recurrence and re-intervention is close to 90%.9-11

In summary, surgery has an important role to play in the management of CMI despite the advances in the endovascular interventions. Surgical interventions are first line in cases with extensive disease, patients with contrast allergy, lack of access, and subsequent to failed endovascular interventions. We could successfully manage our patient with a retrograde aorta - SMA bypass graft.

References

- Zeller T, Macharzina R. Management of chronic atherosclerotic mesenteric ischemia. Vasa. 2011;40:99–107.

- Oderich GS, Bower TC, Sullivan TM, et al Open versus endovascular revascularization for chronic mesenteric ischemia: risk-stratified outcomes. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:1472-1479.e3.

- Park WM, Gloviczki P, Cherry KJ, et al. Contemporary management of acute mesenteric ischemia: Factors associated with survival. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:445–52.

- Brown DJ, Schermerhorn ML, Powell RJ, et al. Mesenteric stenting for chronic mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42:268–74.

- Andraska E, Haga L, Li X, et al. Retrograde open mesenteric stenting should be considered as the initial approach to acute mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2020;72:1260–8.

- Maitrias P, Reix T. Unusual mesenteric revascularization. J Vasc Surg. 2018;67:319.

- Murakami Y, Toya N, Fukushima S, et al. Ascending aorta-common hepatic artery bypass for mesenteric revascularization. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;32:51–3.

- Huerta CT, Orr NT, Tyagi SC, et al. Direct Retrograde Bypass is Preferable to Antegrade Bypass for Open Mesenteric Revascularization. Ann Vasc Surg. 2020;66:263–71.

- Flis V, Mrdža B, Štirn B, et al. Revascularization of the superior mesenteric artery alone for treatment of chronic mesenteric ischemia. Wien KlinWochenschr. 2016;128:109–13.

- Cunningham CG, Reilly LM, Rapp JH, et al. Chronic visceral ischemia. Three decades of progress. Ann Surg. 1991;214:276–87.

- Jimenez JG, Huber TS, Ozaki CK, et al. Durability of antegrade synthetic aortomesenteric bypass for chronic mesenteric ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:1078–84.