Introduction

Gastrointestinal endoscopy (GIE) is one of the best available diagnostic and therapeutic tool for a wide variety of GI disorders in children. The most frequently performed procedures are upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGIE) and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy (LGIE). Recently, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic ultrasound, enteroscopy, capsule endoscopy and manometry are also being increasingly performed. Over the past decades, advances have been made in the rapid evolution of pediatric GIE procedures. GIE is now widely performed due to the improvement in endoscope designs and accessories, availability of trained endoscopist, safe sedation, and increasing acceptability by parents.

Appropriate indications for GIE in children were recently modified by American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN). ASGE and NASPGHAN recommended that endoscopy in children should be performed by paediatric-trained endoscopists whenever possible. However, adult-trained endoscopists in conjunction with paediatricians can perform GI endoscopy in children1,2. In the underdeveloped or developing world, however, use of GIE in paediatrics patients is still not very widely available. Lack of adequately trained physician who can safely perform the procedure, along with the lack of well-equipped paediatric endoscopy units in low-income countries are the greatest hurdles. Hence, many paediatric endoscopic procedures are still performed by adult gastroenterologists3-6.

Diagnostic paediatric endoscopic procedures are usually safe, and complications are rarely encountered. Complications mostly occur due to sedation and general anaesthesia (GA) administered during the procedure. Recently published ESPGHAN (The European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition) guideline suggested performing UGIE in children under GA or only if GA is not available, under deep sedation in a carefully monitored unit. However, recommendation was based on low-quality evidence7. Studies have revealed that UGI endoscopies can be safely performed in unsedated children3,8.

Both UGIE and LGIE examinations can be performed safely in neonates as small as 1.5 to 2 kg. UGIE in children >1-year of age or weighing >10 kg are mostly performed by standard adult gastroscopes. For UGIE in children weighing <5 kg, paediatric gastroscopes (outer diameter 4.9 to 6.0 mm) are required. Adult gastroscopes should usually be avoided in children weighing 5 to 10 kg. Use of adult gastroscope in children weighing 5 to 10 kg can be attempted by highly skilled endoscopists. The main problem with all paediatric endoscopes is a small (2.0-mm) working channel9.

There is limited data regarding the appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic indications and outcomes of paediatric GIE procedures performed by the adult gastroenterologist3-6. We aimed to investigate indications of the GIE, use of sedation, endoscopic findings, outcomes and complications of paediatric endoscopic procedures performed by adult gastroenterologists at a tertiary care teaching hospital. We also evaluated the success rate of UGIE performed by adult gastroscopes in children weighing 5 to 10 kg.

Methods

Study Design

This is a retrospective data analysis conducted in the Department of Gastroenterology at a tertiary care teaching hospital in Eastern India. Data was collected from records of patients who underwent UGIE and LGIE (colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy) from June 2015 to June 2020. Patients from paediatric age group up to 15 years were included. The data regarding the indications of GIE, use of sedation, endoscopic findings, outcomes and complications of therapeutic interventions were reviewed and analyzed. Patients with incomplete data were excluded from the study. The study approval by the institutional review boards was obtained.

Patient Selection and Pre-endoscopy Preparation

UGIE was performed after 6 hours of fasting. For a colonoscopy, in addition to fasting, bowel preparation is required. In infants, adequate preparation was obtained with the use of small-volume enema by substituting clear liquid or milk for 12 to 24 hours. In older children and adolescents, bowel preparation was done with polyethylene glycol and electrolytes (PEG-ELS). Sigmoidoscopy was performed after soap water enema or proctoclysis enema.

Standard pre-procedural preparation in unsedated patients included topical anaesthesia (Xylocaine spray or jelly), vital-sign monitoring with an electronic monitor, and oxygen-supplementation. Pre-procedural parental counseling was done in all cases. Parental presence at the time of endoscopy was sometimes allowed to reduce anxiety of children during unsedated GIE. Sedation or GA was given in those patients who did not tolerate unsedated procedure. Sedation or GA was also given in patients whose parents were not willing for unsedated UGIE and sigmoidoscopy. Colonoscopy was performed under sedation or GA. Mild sedation was induced with intravenous midazolam and fentanyl under supervision of a paediatrician. General anaesthesia with propofol or ketamine was induced by an anaesthetist.

Endoscopy Procedures

Our center does not have a paediatric gastroenterologist, thus, all the paediatric endoscopic procedures are performed by adult gastroenterologists of more than 10 year of experience in performing GIE procedures. UGIE in all children >1-year of age or weighing >10 kg, was performed by a standard adult gastroscope. UGIE in children weighing 5 to 10 kg was initially attempted by an experienced adult gastroenterologist with an adult gastroscope. Paediatric gastroscopes was used after failure of the procedure with an adult gastroscope. For UGIE in patient weighing less than 5 kg, a paediatric gastroscope was used.

Clinical details and endoscopy findings were recorded, and biopsies were taken for histopathological examination if needed. Therapeutic endoscopic interventions were done whenever required. After the diagnostic procedures, patients were observed until the reversal of effect of sedation/GA and the child accepted oral fluids without a problem. Unsedated children were observed for at least two-hours after the procedure. In case of therapeutic endoscopy, post-procedure advice was given depending on the type of procedures.

Statistical Analysis

Results were analyzed with Microsoft Excel. All results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median (range), or frequency (%) as appropriate.

Results

During the study period, GIE was performed in 589 patients. Complete data were retrievable in 514 patients (UGIE: 391; LGIE:123). Out of 391 patients, UGIE was successfully completed in 383 (97.95%) patients. Out of 123, colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy were performed in 98 and 25 patients, respectively. Successful LGIE was performed in all except 3 children. We were unable to perform cecal intubation in 3 children. Overall, LGIE was successfully completed in 120 (97.95%) patients (sigmoidoscopy: 98 (81.66%); colonoscopy: 22 (18.33%). Study details are summarized in Table 1.

UGI Endoscopy

The data of 383 patients who underwent successful UGIE were analyzed. Mean (SD) age of patients was 7.7 (3.3) years with a minimum age of 4 months and a maximum of 15 years. Male-female ratio was 2.71:1. Out of 383 patients, weight of 28 (7.83%) children were between 5 to 10 Kg. Among these children, successful UGIE with an adult gastroscope (OD, 9.2 mm) was possible in 23 (82.14%). Out of 28, 5 children required paediatric gastroscopes for successful completion of UGIE. About one-fourth of the children (28%) were given mild sedation/GA for the procedure, while in remaining, no sedation was required (Table 1).

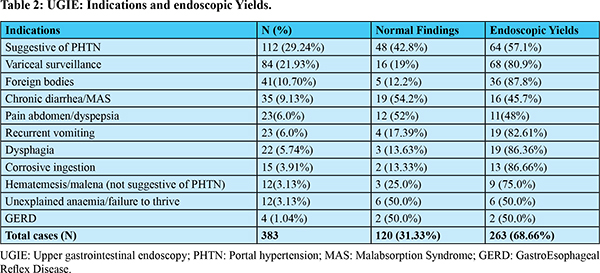

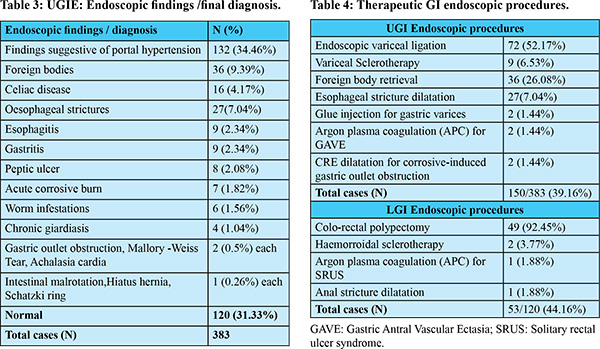

The indications for UGIE and the endoscopic findings have been summarized in Table 2 and 3. Major indications for UGIE were UGI bleeding, portal hypertension (PHT), foreign body ingestion, chronic diarrhoea, abdominal pain and recurrent vomiting. Endoscopy was normal in 120 (31.33%) patients. Overall, endoscopic yield was 68.66%. Symptom wise endoscopic yields have been shown in Table 2. Duodenal biopsy was performed in 57 (14.88%) patients. Chronic diarrhoea, malabsorption syndrome, unexplained anaemia and failure to thrive were the main reasons behind the performance of duodenal biopsy. Out of 383 patients, therapeutic procedures were done in 150 (39.16%). Details of therapeutic procedures are summarized in Table 4.

Adverse events were noted in 22 (5.74%) patients. Minor complications including transient desaturation, sore throat, superficial injury of oral cavity and lips, tongue bite, abdominal bloating, chest discomfort, and vomiting were noted in 19 patients. Two sedated patients severely desaturated during the procedure and recovered after appropriate management. One patient with active variceal bleeding developed aspiration pneumonia and was successfully treated with antibiotics. No other major complications were seen.

LGI Endoscopy

The data of 120 patients who underwent LGIE were analyzed. Mean (SD) age of patients was 7.9 (3.3) years, with a minimum age of 1.5 years and a maximum of 15 years. Male-female ratio was 1.55:1. About one-fourth of the children (27%) were given mild sedation or GA for the procedure, while in remaining, no sedation was required (Table 1).

Major indications of LGIE were per-rectal bleeding [65 (54.1%)], chronic diarrhoea [21 (17.5%)], abdominal pain [15 (12.5%)] and chronic constipation [15 (12.5%)]. Endoscopic findings and diagnosis were colorectal polyps [n=49 (40.8%)], idiopathic ulcerative colitis [n=5 (4.1%)], non-specific proctocolitis/proctitis [n=5 (4.1%)], anal fissure [n=5 (4.1%)], non-specific ileal ulcers [n=4 (3.3%)], intestinal tuberculosis [n=4 (3.3%)], amoebic colitis [n=3 (2.5%)], Cow’s milk induced allergic colitis [n=3 (2.5%)], internal hemorrhoids [n=3 (2.5%)], solitary rectal ulcer syndrome [n=3 (2.5%)], rectal prolapse [n=2 (1.6%)], worm infestations [n=2 (1.6%)], Hirschsprung’s disease [n=1(0.8%)] and anal stricture [n=1(0.8%)]. LGIE was normal in 30 (25%) patients. Overall, endoscopic yield was 75%. Endoscopic yields in major indications of LGIE were per rectal bleeding (90.7%), chronic diarrhoea (47.6%), abdominal pain (66.6%) and chronic constipation (41.6%). Colorectal biopsy was performed in 32 (26.6%) patients. Out of 120 patients, therapeutic procedures were done in 53 (44%) patients. Details of therapeutic procedures have been summarized in Table 4.

Adverse events were noted in 8 (6.6%) of patients. Minor complications, including transient desaturation, abdominal pain, abdominal distention, vomiting, anal canal abrasion, and post-polypectomy minor bleeding were seen in 8 patients. No other major complications were seen.

Discussion

Our retrospective data analysis of 514 patients revealed that paediatric GIE procedures can be safely and efficiently performed by experienced adult gastroenterologists. The current study also revealed that the majority of children don’t require sedation during UGIE and sigmoidoscopy. Use of adult gastroscope in children weighing 5 to 10 kg can be successfully performed in a proportion of patients.

Data regarding the safety and outcome of paediatric GIE performed by an adult gastroenterologist in an adult suite are limited3-6. In a recent published study (n=822), Wani et al. showed that in the absence of paediatric Gastroenterology services, GIE in children can be safely and effectively performed by experienced adult gastroenterologists if done in cooperation with a paediatrician3. The current study supports the result of the aforementioned study performed by Wani et al. Many training centers in India and around the world are still performing both adult and paediatric endoscopies in the adult endoscopy suite. Paediatric endoscopies in these centers are being performed either by an experienced adult gastroenterologist, or by a senior trainee gastroenterologist under careful supervision of an experienced adult gastroenterologist. At these centers, paediatric endoscopies in younger children are performed in the presence of a paediatric physician. Therefore, we believe that adult gastroenterologists in India and around the world have reasonable skill in doing paediatric endoscopy.

Majority of paediatric GI endoscopies are performed under mild sedation or GA. Data regarding the safety and outcome of pediatric GIE procedures performed without use of mild sedation or GA is scarce. Mild sedation or GA provides the advantage of ease of doing endoscopic procedures due to complete patient immobility and better patient comfort. However, it is associated with increased risk of anaesthesia-related complications11. Sedation-related events represent the most common complications of paediatric GIE12,13. More than half of the UGIE related complications are secondary to anaesthetic agents which can lead to cardiopulmonary compromise11. Use of sedation or GA also entails increased costs, increased procedure time, and utilization of hospital resources. Moreover, many hospitals in underdeveloped /developing countries are facing problems over shortage of an anaesthetist for endoscopic procedures. UGIE and sigmoidoscopy can be performed even without sedation or anaesthesia in paediatric patients3,8,14,15. An unsedated procedure can be cost-effective and time saving, which are important in busy endoscopy units of low-income countries. In a study by Bishop et al., successful completion of UGIE was similar for sedated (96.3%) and unsedated (95.2%) children. Total procedure time was significantly longer in sedated versus unsedated children, reflecting longer preparation and recovery8. In another recent study, UGIE was performed with no sedation, mild sedation and GA in 30%, 55% and 15% of patients, respectively3. In our study, the majority of children didn’t require sedation during UGIE (71.54%) and LGIE (73.33%). Overall, about one-fourth of children underwent the UGIE and LGIE under either conscious sedation or GA (Table 1). Colonoscopy procedures were always performed with sedation or GA.

Smaller endoscopes and accessories are required for the evaluation of the smaller and more angulated antrum and duodenum of infants and young children. Small-calibre accessories including biopsy forceps, polyp snare, Roth net retriever, alligator forceps, rat-tooth forceps, injection needles, and argon plasma coagulation (APC) probe can fit in the single small working channel of most paediatric endoscopes. However, the small working channel makes suctioning more difficult and limits the ability to use paediatric endoscopes for therapeutic manoeuvers. Through-the-scope dilatation, CRE dilatation, EBL, haemostatic clip deployment and cyanoacrylate glue injection are generally performed with adult endoscopes9. Moreover, many endoscopy centers in low-income countries still do not have paediatric gastroscopes of different diameters due to cost issue. We were able to perform successful endoscopy using adult gastroscopes in 82% of children weighing 5-10 kg.

The commonest indication for patients undergoing UGIE in our study was PHT, followed by chronic diarrhoea and foreign body ingestion. Esophageal variceal bleeding was the most common cause of UGI bleeding in this cohort. Esophageal varices were treated mainly with endoscopic band ligation (EBL). Endoscopic sclerotherapy (EST) was mainly done in younger children (<8-10 kg). Endoscopic profile of children with UGI bleeding was nearly similar to previous studies published from this part of the world16,17.

Foreign body ingestion is a common indication of UGIE18. Coin ingestion is the most common foreign body ingestion. Devices available for foreign body retrieval are rat tooth forceps, alligator forceps, Roth net retriever, magnets, 3-prong-graspers, and stone retrieval basket. Choice of appropriate device is important for the successful removal of foreign bodies18. We prefer Roth net retriever for eroded button batteries, pencil batteries, food bolus, stones and glass marble balls (kanche). The stone retrieval basket was also used for removal of stones and glass marble balls. Rat tooth forceps or 3-prong-graspers were preferred for safety pins, fish or meat bone, bottle caps and finger rings. Coins and button battery were retrieved with either Roth net retriever, alligator forceps or magnets. The magnet was also used for removal of nails. In the current study, foreign body retrieval was successful in all patients.

Corrosive injury is the most common cause of benign esophageal strictures in Indian children19. In the current study, esophageal stricture in paediatric population was mainly caused by corrosive ingestion and anastomotic stricture after tracheoesophageal fistula and esophageal atresia repair. The majority of patients underwent guide-wire-assisted esophageal dilation without the fluoroscopy [n=22/27 (81.48%)]. Contrast study was done before dilatation. Fluoroscopy-assisted esophageal dilation was performed in patients with tortuous or multiple strictures, and after unsuccessful guide-wire-assisted esophageal dilation without the fluoroscopy. In general, fluoroscopy is recommended for monitoring the position of the guide wire and dilator. However, available data suggests that fluoroscopy is not always necessary for wire guided dilation in esophageal strictures20,21. Use of fluoroscopy involves increased costs, increased procedure time and radiation exposure. Moreover, X-ray machine may not be readily available during endoscopic procedures.

LGIE is very useful in the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal diseases with good success rate and low complication rate. The lower weight limit for use of a standard adult or pediatric colonoscope is 12 to 15 kg9. In children weighing between 5 and 12 kg, colonoscopy can be performed by using an infant or standard adult gastroscope22. Children weighing less than 5 kg may undergo successful colonoscopy with ultrathin gastroscope.

Rectal bleeding is the commonest indication for LGIE, followed by chronic colitis, abdominal pain and constipation. In a study from India, juvenile polyps were the commonest lesions (69.4%) seen in pediatric patients with LGI bleeding23. The diagnosis of idiopathic ulcerative colitis, acute colitis, tuberculous colitis, amoebic colitis and allergic colitis was made in 5.5%, 4.2%, 2.7%, 1.3% and 1.3% cases, respectively23. A multi-center study from East Asia showed that eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders (EGIDs) (43%%), non-specific colitis (23%) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (11%) were more common than polyp (6.8%) and haemorrhoids (1.1%) in infant and young children (<2 years). In older children (2-6 years), polyp (26%) and IBD (22%) are the more common cause of LGI bleeding compared to EGIDs (12%), non-specific colitis (12%) and haemorrhoids (9.3%)24.

Therapeutic LGIE procedures such as snare polypectomy, APC, haemorrhoid banding and haemorrhoid sclerotherapy are performed using adult colonoscope or adult gastroscope. Details of therapeutic LGIE procedures performed in the current study are summarized in Table 4. Recto-sigmoid polyps are the most common cause of rectal bleeding in children and the majority of them are juvenile polyps. Polypectomies are the most common therapeutic LGIE procedure performed in paediatric patients. In a study out of 47 therapeutic LGI endoscopies, colonoscopic polypectomy was performed in 92% patients, followed by anal dilatation and hemorrhoid banding in 4% each25. In our study, per-rectal bleeding was the most common reason to have a LGIE. Colorectal polyps were the most common endoscopic diagnosis. Most of the polyps were juvenile polyps (94%) located in the rectum and left colon. Successful removal of polyps was done with snare polypectomy. Piecemeal polypectomies were required in two patients with large polyps. Prior submucosal injection was done for removal of sessile polyps. Endoloop were applied in large pedunculated polyps. One patient had major bleeding after polypectomy which was controlled by hemostatic clip application.

There are a few limitations of our study, which are the relatively small sample size, and a single-center study.

Conclusion

Paediatric GIE can be safely performed by an experienced adult gastroenterologist. Unsedated UGIE and sigmoidoscopy procedures can be well-tolerated by paediatric patients when performed with appropriate monitoring. Endoscopy in children weighing 5 to 10 kg can be attempted and successfully performed with adult gastroscopes. Esophageal stricture can be safely treated with guide-wire-assisted esophageal dilation without the fluoroscopy.

References

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Lightdale JR, Acosta R, Shergill AK, Chandrasekhara V, Chathadi K, Early D, et al.; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Modifications in endoscopic practice for pediatric patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014; 79:699-710.

- Hassall E. Requirements for training to ensure competence of endoscopists performing invasive procedures in children. Training and Education Committee of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (NASPGN), the Ad Hoc Pediatric Committee of American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the executive council of NASPGN. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1997; 24: 345-47.

- Wani MA, Zargar SA, Yatoo GN, Haq I, Shah A, Sodhi JS, et al. Endoscopic Yield, Appropriateness, and Complications of Pediatric Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in an Adult Suite: A Retrospective Study of 822 Children. Clin Endosc. 2020; 53:436-42.

- Alatise OI, Anyabolu HC, Sowande O, Akinola D. Paediatric endoscopy by adult gastroenterologists in Ile-Ife, Nigeria: A viable option to increase the access to paediatric endoscopy in low resource countries. Afr J Paediatr Surg. 2015; 12:261-65.

- Joshi MR, Sharma SK, Baral MR. Upper GI endoscopy in children-in an adult suite. Kathmandu Univ Med J . 2005; 3:111-14.

- Hayat JO, Sirohi R, Gorard DA. Paediatric endoscopy performed by adult-service gastroenterologists. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008; 20:648-52.

- Tringali A, Thomson M, Dumonceau JM, Tavares M, Tabbers MM, Furlano R, et al. Pediatric gastrointestinal endoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) and European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) Guideline Executive summary. Endoscopy. 2017; 49: 83-91.

- Bishop PR, Nowicki MJ, May WL, Elkin D, Parker PH. Unsedated upper endoscopy in children. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002; 55: 624-30.

- ASGE Technology Committee, Barth BA, Banerjee S, Bhat YM, Desilets DJ, Gottlieb KT, Maple JT, et al. Equipment for pediatric endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012; 76: 8-17.

- Park JH. Role of colonoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of pediatric lower gastrointestinal disorders. Korean J Pediatr. 2010; 53:824-29.

- ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Ben-Menachem T, Decker GA, Early DS, Evans J, Fanelli RD, Fisher DA, et al. Adverse events of upper GI endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012; 76:707-18.

- Mahoney LB, Lightdale JR. Sedation of the pediatric and adolescent patient for GI procedures. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2007; 10:412-21.

- Dar AQ, Shah ZA. Anesthesia and sedation in pediatric gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: A review. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2010; 2:257-62.

- Balsells F, Wyllie R, Kay M, Steffen R. Use of conscious sedation for lower and upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examinations in children, adolescents and young adults: a twelve year review. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997; 45:375–80.

- Khan MR, Ahmed S, Ali SR, Maheshwari PK, Jamal MS. Spectrum of Upper GI Endoscopy in Pediatric Population at a Tertiary Care Centre in Pakistan. Open Journal of Pediatrics. 2014; 4 :180-184

- Yachha SK, Srivastava A, Sharma BC, Khanduri A, Baijal SS. Therapeutic gastrointestinal endoscopy. Indian J Pediatr. 1996; 63:633-39.

- Mittal SK, Kalra KK, Aggarwal V. Diagnostic upper GI endoscopy for hemetemesis in children: experience from a pediatric gastroenterology centre in north India. Indian J Pediatr. 1994; 61:651-4.

- Seo JK. Endoscopic management of gastrointestinal foreign bodies in children. Indian J Pediatr. 1999;66(1 Suppl): S75-S80.

- Poddar U, Thapa BR. Benign esophageal strictures in infants and children: results of Savary-Gilliard bougie dilation in 107 Indian children. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001; 54:480-84.

- Sami SS, Haboubi HN, Ang Y, Boger P, Bhandari P, Caestecker JD, et al. UK guidelines on oesophageal dilatation in clinical practice. Gut. 2018; 67:1000-23.

- Pieczarkowski S, Woynarowski M, Landowski P, Wilk R, Daukszewicz A, Toporowska-Kowalska E, et al. Endoscopic therapy of oesophageal strictures in children - a multicentre study. Prz Gastroenterol. 2016; 11:194-99.

- Gan T, Zhang MG. [An adult gastroscope instead of an adult colonoscope for colon examination in children]. Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi. 2008;10(3):346-8.

- Thapa BR, Mehta S. Diagnostic and therapeutic colonoscopy in children: experience from a pediatric gastroenterology centre in India. Indian Pediatr. 1991; 28:383-89.

- Nambu, R., Hagiwara, S., Kakuta, F, Hara T, Shimizu H, Abukawa D, et al. Current role of colonoscopy in infants and young children: a multicenter study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2019; 19: 149.

- Yachha SK, Srivastava A, Sharma BC, Khanduri A, Baijal SS. Therapeutic gastrointestinal endoscopy. Indian J Pediatr. 1996; 63:633-39.