|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Original Articles |

|

|

|

|

|

Keywords :

Inflammatory bowel disease, Ulcerative colitis, Adherence, Non-adherence. |

|

|

|

Surender Kumar, Rishabh Gupta, Hitesh Kumar Sharma, Sudhir Maharshi, Kamlesh Kumar Sharma, Vijyant Tak, Rupesh Kumar Pokharna Department of Gastroenterology, Sawai Man Singh Medical College, Jaipur, India.

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Rupesh Kumar Pokharna Email: rkpokharna2@rediffmail.com

DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.7869/tg.754

Abstract

Background / Aim: Non-adherence to treatment is an important determinant of relapses and complications in Inflammatory bowel disease-ulcerative colitis (IBD-UC). We assessed the adherence to treatment advised in IBD-UC and reasons for non-adherence in tertiary government hospital. Methods: This cross-sectional study included patients with histologically confirmed IBD-UC admitted indoor as well as those visiting outdoors between December 2020 and August 2023. Non-adherence to treatment was assessed on the basis on questionnaire and defined as medicine intake less than 80% in last two weeks. Results: A total of 178 participants completed the questionnaire, mean age (34.17±12.3 years), average disease duration was 3.47±2.7 years, and 56 (31.5%) patients were adherent to treatment. The adherence to oral mesalamine, salfasalazine, azathioprine, oral prednisolone, tofacitinib and topical mesalamine were 38.2%, 31.3%, 66.7%, 77.8%, 83.3% and 33.3% respectively. 78 patients were receiving treatment free-of-cost, among them 31 (39.7%) were adherent. The primary reasons for non-adherence among patients were cost and unavailability (33.1%), feeling better without medications (22.9%) and forgetfulness (12.7%). Univariate analysis revealed significant association of adherence with satisfaction (p=0.001), number of hospital visits (p=0.001) and disease awareness (p=0.014). Factors such as demographics, disease characteristics and bearing treatment-cost showed no statistically significant association. Regression analysis identified patient-satisfaction as the sole predictor of medication adherence (p = 0.001). Conclusion: One-third of patients with UC adhered to medication regimens. Adherence was significantly associated with patient satisfaction, number of hospital visits and disease awareness while education, socioeconomic status, and disease characteristics showed no association. Free-of-cost treatment did not make a difference in adherence.

|

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease- ulcerative colitis (IBD-UC) is a chronic and relapsing disease that usually requires lifelong treatment. The treatment often requires frequent dosing, multiple pills per day, inconvenient administration methods such as enemas and infusions. Additionally, it imposes financial burden on the health care along with the possibility of adverse effects. Non-adherence to these prescribed treatment regimens has emerged as a significant factor contributing to the recurrence of IBD symptoms.1 Worldwide, many studies on IBD patients have revealed significant non adherence. However, the rates of adherence in studies exhibited significant heterogeneity based on factors such as the demographic composition of study participants (distinguishing between adults and pediatric patients), the chosen method of administration, and the diverse approaches employed for measuring adherence (including blood analysis, pharmacy refill records, and self-report methods such as diaries, interviews, and questionnaires). A comprehensive systematic review encompassing 17 studies comprising a total of 4,322 adult subjects with IBD revealed non-adherence rates to oral medications ranging from 7% to 72%.2 Non-adherence to prescribed treatment regimen is associated with increased risk of relapses in individuals with IBD, leading to a deterioration in their quality of life and imposing increased social and personal costs.1,3,4,5 Factors influencing adherence in IBD patients including demographics, clinical aspects, psychosocial elements, and cost of treatment have been explored in multiple studies.1,3,5-16 Previous studies from India examined the relationship between a variety of factors and medication non-adherence and showed contrasting results. Percentage adherence in one study being 82.4%, while in another, it was only 19%.5-6 One of the studies concluded that higher education status, professional occupation and upper socioeconomic status were predictors of non -adherence.6 However, factors such as inconvenient drug administration, distance from the drug distribution centre, and satisfaction with treatment advice on drug adherence have not been addressed. Cost of treatment may be an important factor affecting adherence as drugs in IBD are expensive. Under Government Schemes, free treatment is available only at few centers in India. Enhancing medication adherence presents a significant challenge for healthcare providers treating individuals with IBD. In this study, we aimed to identify adherence and reasons for non-adherence in a government-funded Tertiary Care Hospital.

Methods

Study Design and Population: This cross-sectional study was conducted at the Gastroenterology Department, SMS Medical College, Jaipur in patients with histologically confirmed ulcerative colitis admitted inpatient / wards as well as those visiting outpatient clinics between December 2020 and August 2023. Newly diagnosed patients (diagnosed within the past 2 months) and those who did not give consent or were unable to answer the questionnaire were excluded. A printed simple proforma questionnaire was prepared that included personal and socio-demographic profiles, disease characteristics (from previous treatment records) and number of hospital visits in last 12 months of study subjects. The socio-demographic characteristics were defined according to modified Kuppuswamy socioeconomic scale for the year 2022. The direct expenditure of patients for treatment, including physician consultation and hospitalization, was free for all patients. Laboratory investigations, diagnostic procedures, and prescription drugs were free of cost for a select group of patients while subsidized for others. The questionnaire needed information (based on recall from the previous 2 weeks) on the intake of prescribed medication, frequency of missed doses and reason for non-adherence to prescribed medications. Non-adherence to treatment was defined as medication intake < 80% of the dose advised.1 The patients’ recall of medicine intake in the last 2 weeks was used to calculate non-adherence.5 Patient satisfaction was assessed by Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and scored from 0 to 100 point with extremes of satisfaction at either ends and a cut-off of 50 point was taken for satisfaction. Awareness about disease was assessed based on the patient knowledge about need of lifelong treatment and importance of adherence. The study received institute’s ethics committee approval prior to enrollment. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Statistical Analysis: The data was initially entered into Microsoft Excel. Nominal and categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were summarized using mean and standard deviation. Proportional significance testing was conducted through the analysis of proportions using the Z test and the univariate analysis using chi-square test. A p value of = 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Regression analysis was done to study the factors affecting adherence. Regression analysis was performed using linear regression where the dependent variable was a continuous variable, and multiple regression if the dependent variable was a categorical variable. Significance value / p value for independent variables was reported and those less than 0.05 were considered as significant variables affecting the dependent variable. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 12, IBM software. To calculate the adherence rate, the following formula was used: Percentage of adherence of drug (in %) = (Number of dose taken)/(Number of doses prescribed in 2 weeks period) x 100 The resulting percentage of adherence ranged from 0 to 100%.

Results

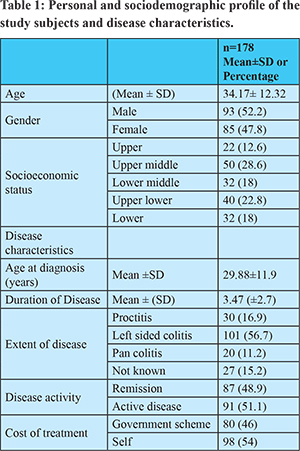

One hundred eighty-six patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) were initially screened. However, eight patients were excluded because they had been newly diagnosed within the past two months. Out of the remaining 178 patients, gender distribution was nearly equal comprising 93 (52.2%) males and 85 (47.8%) females. Mean age of participants at the time of recruitment and diagnosis was 34.1±12.3 years and 29.8 ±11.9 years, respectively. Most patients were unemployed and belonged to lower socioeconomic strata. Mean duration of disease was 3.4 ± 2.7 years. The majority of patients, 131 (73.6%), exhibited left-sided colitis or proctitis, 20 (11.2%) had pancolitis, and 27 (15.2%) had an unknown extent of the disease. None of the study patients had undergone surgery for IBD. 87 (48.9%) patients were in remission. The mean number of relapses was 2.04 ± 1.1 (Table 1).

The mean number of hospital visits in one year was 7.08±3.9. Regarding cost of treatment, 78(43.8%) patients availed free treatment, and 98 (54%) paid for their treatment. In our study 1/3rd of patients- 56 (31.5%) adhered to their prescribed treatment. Among the prescribed medications, oral mesalamine was prescribed in 159 patients; however, only 68 (38.2%) patients demonstrated adherence. 16 patients were on sulfasalazine, out of which 5 (31.3%) adhered to the treatment. For oral prednisone, prescribed in 29 of patients, 21 (77.8%) exhibited adherence. Oral azathioprine was prescribed to 51 patients and 34 (66.7%) exhibited adherence. Oral tofacitinib, was prescribed for only 6 patients, and 5 (83.3%) of them were adherent. Topical ASA was prescribed to 48 patients, and 16( 33.3%) of them were adherent.106 patients were on multiple drugs. None of our patients were on biologicals. A total of 141 (79.2%) out of 178 patients were satisfied with their treatment. The primary reasons for non-adherence to medications among the patients in the study were diverse. The most cited reasons included the cost or unavailability of medications, reported by 39 (33.1%) patients. Of non-adherent patients, 27 (22.9%), indicated that they felt better without medications, while 15 patients (12.7%) reported forgetfulness as a contributing factor. 11 out of 32 patients non-adherent to topical ASA cited inconvenient routes of drug administration as a reason for non-adherence (34%). Other reasons for non-adherence included the perception of lifelong treatment, seeking alternative treatments, experiencing adverse drug events and frequent drug dosing in decreasing frequency. (Table 2)

Out of the 80 patients who received free treatment, 31 (39.7%) were adherent, whereas among the 98 patients who bore the cost of their treatment, 25 (25.5%) adhered to the prescribed treatment regimen. Univariate analysis of factors influencing medication adherence suggested significant relation to patient satisfaction (p = 0.001), disease awareness (p = 0.014) and frequency of hospital visits in the last year (p = 0.001). On the other hand, our analysis revealed that factors such as age, sex, rural or urban residence, education, socioeconomic status, age of onset, disease duration, extent of the disease and disease activity did not show statistically significant difference. Other factors, such as the distance from the drug distribution center, the use of multiple drugs and the addition of topical agents did not demonstrate statistically significant associations with medication adherence. The difference in adherence between patients who availed free treatment and those who bore treatment cost was not statistically significant (p = 0.082). However, regression analysis highlighted that, among these factors, patient satisfaction with treatment remained the sole statistically significant predictor of compliance (p = 0.001). (Table 3)

Discussion

Maintaining drug adherence is of paramount importance for effectively managing chronic conditions such as IBD-ulcerative colitis (UC). It demands continuous monitoring to ensure treatment support and adherence. Non-adherence has been associated with an increased risk of relapse, adverse outcomes such as reduced quality of life, missed workdays, poor pregnancy outcomes, and even colorectal cancer.1,17-24 Moreover, it significantly escalates healthcare costs.25 Thus, recognizing and addressing non-adherence is essential to enhance patient outcomes and alleviate economic burdens. In this study, involving 178 patients (mean age 34 year, 52% males) with ulcerative colitis (UC), we observed that patient demographics and disease characteristics varied considerably. Notably, a substantial portion of patients (68.5%) exhibited non-adherence with prescribed medications, with reasons ranging from cost or unavailability of medicines to “felt better without treatment”. Worldwide, studies on IBD patients revealed significant non-adherence trends. In a multicenter study from Argentina, 50.3% of patients reported inadequate adherence to oral medications; another study from the Czech Republic found that 32% reported intentional non-adherence, with 42% reporting unintentional.26-27 The documented rates of medication non-adherence among Asian patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) falls within the range of 20% to 30%.28-29 In earlier Indian studies, Tomar SK et al. from Delhi, found that 82.4% of patients with ulcerative colitis patients were adherent with therapy.6 In another study by Jay Bhatt et al from Mumbai, 19% of the patients with IBD (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease) were adherent with therapy.5 Compared to the above studies, we included only patients with ulcerative colitis, resulting in a more homogenous population. The adherence rate in our study was 31.5%. If we reduce the diagnostic threshold of adherence to more than 60% of total advised dose (in contrast to pre-defined 80%) then adherence in the study by Jay Bhatt et al would be 87.4%, while in our study, it would have been 50%.5 (Table 4). In our study, patients on oral steroids, azathioprine and tofacitinib were more adherent, highlighting that having extensive disease or having frequent relapses that led to the use of these drugs, resulted in improved adherence; this is in compliance with study by Tomar SK et al. where adherence to steroids (100%) was more than overall adherence rate (82.4%).

Common reasons for non-adherence in the study by Tomar SK et al. were forgetting doses (19.6%), unavailability of medications (13.2%), “feeling better without medications” (12.7%), and side/adverse effects (4.9%) whereas in the study by Jay Bhatt et al, the main reasons for non-adherence were forgetfulness (77%), feeling better (14.17%), high frequency of doses (10.1%), and no effect of medications (7.87%).5-6 In our study, we found that common reasons for non-adherence included the cost or unavailability of medications (33.1%), feeling better without medications (22.9%), and forgetfulness (12.7%), which is in sharp contrast to study by Jay Bhatt et al, possibly owing to increased availability of sustained release tablets. World-wide, numerous studies have identified diverse predictors of non-adherence. In a Korean study non-adherence was associated with younger age, longer outpatient intervals and limited medication knowledge, this is in concordance with our study that awareness about disease and regular follow up are important determinants of adherence.30 In a Spanish study, forgetfulness, feeling better, feeling worse, carelessness, long-standing IBD, inadequate knowledge, high depression scores, patient-physician discordance were predictors of non-adherence.31 A study from Italy related non-adherence with disease duration, significant association with forgetfulness, feeling better, feeling worse, frequent dosing, topical therapy.35 In all these studies feeling better on treatment is important contributor for non adherence. A Belgian Study in 2016 revealed age younger than 40 years, higher education, unmarried status and mesalamine use as predictors of non-adherence while self-employment as protective.32 In a study from Prague, non-adherence was associated with higher education, medication side effects while factors associated with adherence were older age. Non-adherent patients more likely had chronically active or relapsed disease state.33 Our statistical analysis revealed compelling associations between adherence and specific factors emphasizing the significant impact of patient satisfaction, hospital visit frequency, and awareness about the disease on adherence behavior. In the study by Tomar SK et al, patient’s level of education (p<0.001), occupation (p=0.097), and socioeconomic status (p=0.021) exhibited an inverse correlation with adherence.6 Interestingly, individuals in higher socioeconomic brackets with professional educational and occupational backgrounds demonstrated the lowest adherence rate (47%). Conversely, patients from lower socioeconomic strata, characterized by lower educational attainment and unemployment, displayed the highest adherence rate (100%). In our study, patient education (p=0.875) and socioeconomic status (p=0.735) did not show a significant association with non-adherence. Our study investigated the impact of drug administration routes on patients’ adherence. Among the 48 patients receiving topical ASA, 16 (33.3%) adhered to treatment prescribed, while 11 out of 32 adherent patients cited inconvenience to drug administration as primary reason for non-adherence. This aligns with previous study by Prantera et al (a randomized controlled trial) that demonstrated higher adherence rates with oral 5-ASA compared to topical 5ASA (97.0% vs. 87.5%). D’Incà et al., also demonstrated in their real-world study that, there is increased non-adherence with rectal therapy compared to oral therapy (68% vs. 40%, p=0.001), mainly due to patients’ discomfort and administration inconvenience.34-35 In our study population, some of the direct expenditures of treatment, including physician consultation and hospitalization, were free of cost. Other expenditures, including prescription drugs for a limited period, laboratory investigations, and diagnostic procedures were either subsidized or free under the Government Scheme. Apart from these, the indirect cost, including logistics and loss of workdays plays an important role, as most of our patients belonged to remote areas. Nevertheless, adherence remains suboptimal even among those who receive free treatment (39.7%), and there is no statistically significant difference compared to those who received subsidized treatment (p=0.082). This observation suggests that factors other than cost alone play a crucial role as major determinants of adherence. Our study is not without limitations, as our study was retrospective based on recall, which is subject to overestimation. The patients in our study were in different stages and duration of disease which would have affected adherence pattern, and we did not extensively analyze the direct and indirect cost of the treatment.

Conclusion

One-third of patients adhered to medication regimens. Adherence was significantly associated with patient satisfaction, disease awareness and hospital visits while education, socioeconomic status, and disease characteristics showed no association. Free-of-cost treatment did not make a difference in adherence.

References - Kane S, Huo D, Aikens J, Hanauer S. Medication non-adherence and the outcomes of patients with quiescent ulcerative colitis. Am J Med. 2003;114(1):39–43.

- Jackson CA, Clatworthy J, Robinson A, Horne R. Factors associated with non-adherence to oral medication for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):525-39.

- Robinson A. Improving adherence to medication in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment PharmacolTher. 2008;27(Suppl 1):9–14.

- Higgins PDR, Rubin DT, Kaulback K, Schoenfield PS, Kane SV. Impact of non-adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid products on the frequency and cost of ulcerative colitis flares. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(3):247–57.

- Bhatt J, Patil S, Joshi A, Abraham P, Desai D. Self-reported treatment adherence in inflammatory bowel disease in Indian patients. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2009;28(4):143–6.

- Tomar SK, Kedia S, Singh N, Upadhyay AD, Kamat N, Bopanna S et al. Higher education, professional occupation, and upper socioeconomic status are associated with lower adherence to medications in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. JGH Open. 2019;3(4):302-309.

- Lenti MV, Selinger CP. Medication non-adherence in adult patients affected by inflammatory bowel disease: a critical review and update of the determining factors, consequences, and possible interventions. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;11(3):215–26.

- Herman ML, Kane SV. Treatment nonadherence in inflammatory bowel disease: identification, scope, and management strategies. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(10):2979–84.

- Jackson CA, Clatworthy J, Robinson A, Horne R. Factors associated with non-adherence to oral medication for inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):525–39.

- Hawthorne AB, Rubin G, Ghosh S. Medication non-adherence in ulcerative colitis–strategies to improve adherence with mesalazine and other maintenance therapies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27(11):1157–66.

- Kane SV, Brixner D, Rubin DT, Sewitch MJ. The challenge of compliance and persistence: focus on ulcerative colitis. J Manag Care Pharm. 2008;14(Suppl A):S2-12-15.

- Kane SV. Overcoming adherence issues in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2007;3(10):795–9.

- López-Sanromán A, Bermejo F. How to control and improve adherence to therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24(Suppl 3):45–9.

- Tripathi K, Dong J, Mishkin BF, Feuerstein JD. Patient Preference and Adherence to Aminosalicylates for the Treatment of Ulcerative Colitis. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2021;14:343-351.

- Jayasooriya N, Pollok RC, Blackwell J, Bottle A, Peterson I, Creese H et al. Adherence to 5-aminosalicylic acid maintenance treatment in young people with ulcerative colitis: a retrospective cohort study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2023 26;73(736).

- Wiles CA, Shah NB, Bell J,PablaBS,Scoville EA, Dalal RL et al. Tofacitinib Adherence and Outcomes in Refractory Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Crohn’s Colitis 360. 2021;3(4):otab075.

- Kane S, Huo D, Magnanti K. A pilot feasibility study of once-daily versus conventional dosing mesalamine for maintenance of ulcerative colitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1(3):170–173.

- Hjortswang H, Järnerot G, Curman B, Sandburg-Gertzen H ,Tysk C,Bloomberg B et al. The influence of demographic and disease-related factors on health-related quality of life in patients with ulcerative colitis. Eur J GastroenterolHepatol. 2003;15(9):1011–1020.

- Han SW, McColl E, Barton JR, James P, Steen IN, Welfare MR. Predictors of quality of life in ulcerative colitis: the importance of symptoms and illness representations. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11(1):24–34.

- Vaizey CJ, Gibson PR, Black CM, Nicholls RJ, Westen AR, Gaya DR et al. Disease status, patient quality of life and healthcare resource use for ulcerative colitis in the UK: an observational study. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2014;5(3):183–189.

- Watanabe C, Nagahori M, Fujii T, Yokoyama K, Yoshimura N, Kobayashi T et al. Non-adherence to medications in pregnant ulcerative colitis patients contributes to disease flares and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66(2):577–586.

- Moody GA, Jayanthi V, Probert CS, Mac Kay H, Mayberry JF. Long-term therapy with sulphasalazine protects against colorectal cancer in ulcerative colitis: a retrospective study of colorectal cancer risk and compliance with treatment in Leicestershire. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8(12):1179–1183.

- Velayos FS, Terdiman JP, Walsh JM. Effect of 5-aminosalicylate use on colorectal cancer and dysplasia risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(6):1345–1353.

- van Staa TP, Card T, Logan RF, Leufkens HGM. 5-Aminosalicylate use and colorectal cancer risk in inflammatory bowel disease: a large epidemiological study. Gut. 2005;54(11):1573–1578.

- Kane S, Shaya F. Medication non-adherence is associated with increased medical health care costs. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(4):1020–1024.

- Lasa J, Correa G, FuxmanC,Garbi L ,LinaresME,Lubrano P et al. Treatment Adherence in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients from Argentina: A Multicenter Study. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020 Jan 17;2020:4060648.

- Cerveny P, Bortlik M, Vlcek J, Kubena A, Lukás M. Non-adherence to treatment in inflammatory bowel disease in the Czech Republic. J Crohn’s Colitis. 2007;1(2):77-81.

- Kawakami A, Tanaka M, NishigakiM,Naganuma N ,Iwao Y ,Hibi T et al. Relationship between non-adherence to aminosalicylate medication and the risk of clinical relapse among Japanese patients with ulcerative colitis in clinical remission: a prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(9):1006-15.

- Kim SB, Kim KO, Jang BI,Kim ES ,Cho KB ,Park KS et al. Patients’ beliefs and attitudes about their treatment for inflammatory bowel disease in Korea. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(3):575-80.

- Tae CH, Jung S-A, Moon HS,Seo JA,Song HK,Moon CM et al. Importance of Patients’ knowledge of their prescribed medication in improving treatment adherence in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50(2):157–62.

- López San Román A, Bermejo F, Carrera E, Pérez-Abad M, Boixeda D. Adherence to treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Rev EspEnferm Dig. 2005;97(4):249–57.

- Coenen S, Weyts E, Ballet V, et al. Identifying predictors of low adherence in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(5):503–7.

- Cervený P, Bortlík M, Kubena A, Vlcek J, Lukás M. Nonadherence in inflammatory bowel disease: results of factor analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13(10):1244–9.

- Prantera C, Viscido A, Biancone L, Francavilla A, Giglio L, Campieri M. A new oral delivery system for 5-ASA: preliminary clinical findings for MMx. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11(5):421–427.

- D’Incà R, Bertomoro P, Mazzocco K, Vettorato MG, Rumiati R, Sturniniolo GC Risk factors for non-adherence to medication in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;28(2):156-62.

|

|

|

|

|

|