Myeloid sarcoma (MS), granulocytic sarcoma or chloroma is an extra-medullarytumor consisting of myeloid blasts presenting in the skin, soft tissue and sub-periosteal bone1. MS is usually associated with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Gastro-intestinal tract (GIT) is an unusual site for MS2. Isolated MS in the GIT is rare and presents with non-specific symptoms based onsite; mimicking other conditions like intestinal tuberculosis, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and carcinoma2. We present an interesting case of MS in a young man presenting with recurrent small bowel obstruction causing a clinical diagnostic dilemma.

Case Report

A 35-year-old male without any co-morbidities presented to the gastroenterology OPD with recurrent colicky right-sided abdominal pain since 3 months which was refractory to medical management. There was no history of fever, night sweats or weight loss. There was no history of tuberculosis. Physical examination revealed tenderness in the right iliac fossa. The laboratory parameters were within normal limits (haemoglobin-14.5g/dl, total leucocyte count-8570/µl and platelet count-235000/µl). CT-enterographyshowed an irregular, concentric thickening with enhancement of long segment of distal ileum causing significant luminal narrowing and proximal bowel dilation, suggestive of infective/ inflammatory etiology. The clinical differential diagnosis included tuberculosis and Crohn’s disease. He underwent small bowel resection and anastomosis to relieve his obstructive symptoms.

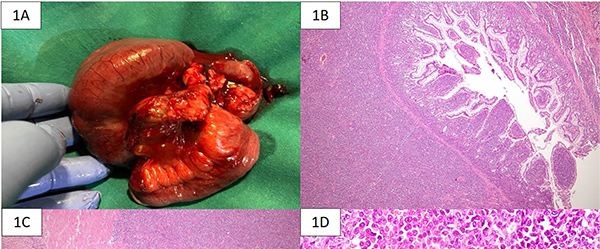

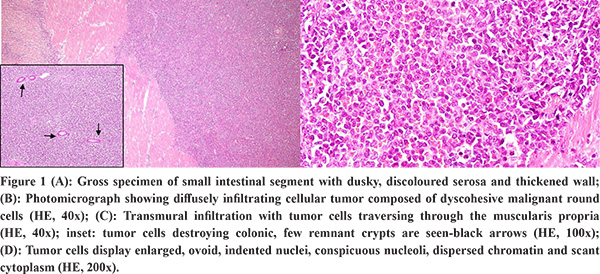

The gross specimen showed dusky serosa, thickened ileal wall with stricture formation (Figure 1A). Histopathology revealed a cellular, infiltrating transmural tumor arranged in dyscohesive sheets causing crypt destruction and bulbous configuration of villous folds (Figure 1B, 1C). Individual tumor cells displayed enlarged, ovoid, indented nuclei, conspicuous nucleoli, dispersed chromatin and scant cytoplasm (Figure 1D). On immunohistochemistry (IHC), tumor cells were positive for Leucocyte Common Antigen (LCA) and negative for pan-cytokeratin (Figure 2A, 2B). Further IHC panel revealed the tumor cells to be negative for pan B-lymphocyte (CD [Cluster-of-Differentiation] 20, PAX [paired-box-containing] 5, CD79a) pan T-lymphocyte (CD3, CD5, CD4, CD8, CD45RO) and histiocytic markers (CD68, Fascin). Tumor cells showed positivity for myeloid markers Myeloperoxidase (MPO) and CD117 (Figure 2C, 2D). Tumor cells showed focal positivity for immaturity marker Tdt (Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase) while other immaturity markers (CD1a, CD10 and CD34) were negative. Tumor cells were positive for ERG (ETS-family-transcription-factor) (Figure 2F). Aberrant positivity for T cell marker (CD43) was noted (Figure 2E). Based on histological and IHC features, a final diagnosis of MS was rendered and a bone marrow (BM) examination was advised.

BM aspiration and biopsy were within normal limits with no increase in blasts. Karyotyping revealed normal cytogenetic study. Fluorescent-insitu hybridization (FISH) for AML panel on the BM was negative. Whole body PET-CT showed post-inflammatory changes in the right iliac fossa without any other avid lesions. A final diagnosis of an isolated MS of ileum was made following which induction chemotherapy for AML was given. Patient is currently on haematological follow-up and doing well 3 months’ post-surgery.

Discussion

MS is an extramedullary tumor of immature granulocytic cells with male predilection(male to female ratio of 1.2:1)3. It is usually seen in older individuals (median patient age of 56 years). Common sites of involvement include lymph nodes, skin, soft tissues, testis, bone, peritoneum, and GIT while multiple anatomic sites maybe involved in less than 10% cases4. MS is seen in 8 to 9% patients with AML. Of these, MS can occur following systemic BM involvement by AML, concomitantly with AML and prior to the diagnosis of AML (isolated form) in 50%, 35% and 25% cases, respectively4. It can also rarely constitute acute blastic transformation into myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or myelo-proliferative neoplasm (MPN). MS may occur following allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in an isolated form or with BM relapse4.

The outcomes of isolated extramedullary MS are unclear. However, delayed or inadequately treated isolated MS almost always progresses to AML with time to development of AML in untreated cases ranging from 5-12 months. The most common cytogenetic abnormality in MS include t(8;21), inversion 16 and 11q23 re-arrangements which may not be detected on the BM in an isolated extramedullary involvement5.

GI involvement by MS most commonly involves the small bowel (10% cases) and presents with bowel obstruction2. Isolated MS involving the GIT is rare (<1% cases)2. Due to its rarity, clinical data is limited to a few case series. Isolated MS in the small intestine is a difficult diagnosis which can be resolved only on histopathology as clinical-radiological findings mimic other entities such as tuberculosis, Crohn’s disease, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and carcinoma6. In the absence of a clinical history of leukemia, MS is often misdiagnosed, most typically as NHL, in up to half the of cases.

On histopathology, MS shows morphology of a malignant round cell tumor with NHL being its closest differential. A broad IHC panel is needed to clinch the diagnosis. MS is negative for cytokeratin and may show positivity for CD45 along with aberrant expression of T-cell or B-cell markers. Histiocytic markers maybe positive especially in monocytic differentiation. However, negativity for pan B cell, T cell and histiocytic markers should prompt the pathologist to perform markers of myeloid differentiation such as MPO, CD117 and recent marker; ERG as well as immaturity markers (Tdt, CD1a and CD34)2. ERG plays an important role in normal and aberrant hematopoiesis2. High expression of ERG has been reported in cytogenetically normal AML in adults2.

The prognosis of isolated MS is poor with majority of patients succumbing to disease without treatment. Isolated MS has longer survival (median 78 months), compared to MS with synchronous intramedullary AML (median 16 months)1,3. Treatment includes surgical resection followed by chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy1,3. Each patient should be assessed individually, according to various prognostic factors when deciding on post-remission strategy. HSCT is considered in patients with extramedullary relapses1.

Conclusion

We report a case of an isolated MS in ileum presenting with small bowel obstruction and a broad clinical differential diagnosis. As isolated MS is very rare; it is vital for the histopathologist to follow an algorithmic IHC panel to confirm diagnosis of MS and avoid misdiagnosis as NHL. It is imperative for these patients to have an early, definitive diagnosis so as to start treatment for AML before BM involvement.

References

- Yamauchi K, Yasuda M. Comparison in treatments of nonleukemic granulocytic sarcoma: report of two cases and a review of 72 cases in the literature. Cancer. 2002; 94:1739-46.

- Kohl SK, Aoun P. Granulocytic sarcoma of the small intestine. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006; 130:1570-4.

- Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, Akkari Y, Alaggio R, Apperley JF, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Myeloid and Histiocytic/Dendritic Neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36: 1703–1719.

- Pileri SA, Ascani S, Cox MC, Campidelli C, Bacci F, Piccioli Met al. Myeloid sarcoma: clinico-pathologic, phenotypic and cytogenetic analysis of 92 adult patients. Leukemia. 2007; 21: 340-50.

- Alexiev BA, Wang W, Ning Y, Chumsri S, Gojo I, Rodgers WH et al. Myeloid sarcomas: a histologic, immunohistochemical, and cytogenetic study. Diagn Pathol. 2007; 31:2–42.

- Guermazi A, Feger C, Rousselot P, Merad M, Benchaib N, Bourrier P et al. Granulocytic sarcoma (chloroma): imaging findings in adults and children. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 178:319-25.