48uep6bbphidvals|145

48uep6bbphidcol4|ID

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Infectious diseases are still remarkably common in developing countries where there is poor personal and communal hygiene. Enteric fever is a major waterborne disease and there has been little, if any, change in the mortality rate over the years.(1,2) Due to its variable presentation, diagnosis is often missed and therapy delayed, further increasing the risk of death.(3,4) Renal cell carcinoma, a malignant tumour of the kidney, first described by Grawitz in 1883, is the commonest tumour of the kidney, commoner in men and has been described across various age groups. Renal cell carcinoma commonly presents with a triad of haematuria, loin pain and flank mass. It may cause non-remitting fever (found in 20% of cases) and abdominal pain. We present a case of enteric fever with suspected intestinal perforation with incidentally detected asymptomatic renal cell carcinoma.

CASE REPORT

A 19-year-old female patient was admitted with a 2-week history of severe headache and high-grade fever. She developed severe, colicky generalised abdominal pain 5 days after the onset of illness and later, progressive abdominal swelling, jaundice and diarrhoea. There was no history of constipation, loin pain, haematuria or haematochezia. She had no previous sexual exposure and had normal menstrual history. She had been managed at a peripheral hospital for enteric fever with no improvement before being referred to us.

On admission, the patient had an axillary temperature of 38.40C. There was a tinge of scleral jaundice but no conjunctival pallor. The pulse was 120 per minute, regular and of normal volume. Blood pressure and respirations were 100/70 mmHg and 35 per minute respectively. The lung fields were clear. The abdomen was uniformly distended with florid signs of peritonitis, as well as ascites. There was tender hepatosplenomegaly and bilateral loin tenderness, which was more on the right side. A tender left loin mass was palpable. Abdominal paracentesis yielded a cloudy yellowish fluid.

A clinical diagnosis of typhoid septicaemia with likely perforation, and right perinephric abscess was made. Pyelonephritis was kept in mind as a differential diagnosis. She later developed clinical features of acute renal failure. Laboratory investigations revealed blood urea: 266 mg/dL, serum sodium: 125 mmol/L, serum potassium: 5.1 mmol/L, serum calcium: 98 mmol/L, serum bicarbonate: 12 mmol/L. PCV: 34%. LFT: Total bilirubin: 6.5 IU/L, alkaline phosphatase: 262 IU/L, AST: 77 IU/L, ALT: 33 IU/L; total serum protein: 6.8 g/dl, serum albumin: 2.3 g/dl. Abdominal ultrasonography showed hepatomegaly and a mass in the upper pole of the right kidney and the causes suspected were haemorrhage, abscess or neoplasm. Random blood glucose was 85 mg/dl. Urine culture was sterile for pathogens and ascitic fluid culture revealed heavy growth of Escherichia coli that was sensitive only to ceftazidime. Urinalysis showed blood +++, protein++ with a specific gravity of 1.025. She was negative for both HIV and hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg). Chest radiograph was normal with no air under the diaphragm. Abdominal x-ray showed distended bowel loops. She was initially placed on intravenous metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, and saline and glucose infusions. On the third day of admission the patient was restless and drowsy and was talking irrationally; uraemic encephalopathy was diagnosed and she subsequently underwent haemodialysis. The antibiotic was then changed to ceftriaxone, based on the culture report of the ascitic fluid. She was deemed unsuitable for surgery by the surgeons. Urea and creatinine post-dialysis were 93 mg/dl and 2.7 mg/dl, respectively. She developed hypotension during the third session of dialysis and this persisted till afterwards. She subsequently suffered cardiovascular collapse due to disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) and gastrointestinal haemorrhage. She died in spite of resuscitative measures.

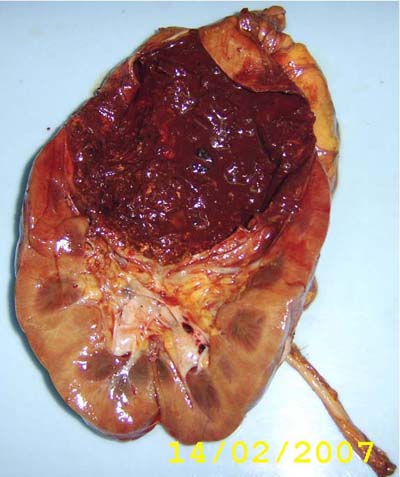

Consent for post-mortem examination was obtained and revealed multiple longitudinal ileal ulcers with an area of perforation (Figure 1), mesenteric lymphadenitis, 1800 ml of ascitic fluid contaminated with faeces and associated fibrinopurulent exudate on the serosal surface of the small and large intestines, and the capsular surfaces of the liver and spleen. Histological findings were consistent with perforated typhoid ileitis and peritonitis. An incidental huge left renal upper pole mass was found. The whole left kidney weighed 1325 g. The mass measured 15 cm by 13 cm by 8 cm in size. Cut section of the left kidney revealed an encapsulated haemorrhagic and necrotic mass, cortical pallor and congested medulla (Figure 2). Histopathological examination of the mass revealed papillary structures lined by cells with clear to granular cytoplasm, consistent with the clear cell variant of renal cell carcinoma (Figure 3). Cause of death was recorded as septic shock.

DISCUSSION

This report emphasises that even where effective antibiotic therapy is availabile, typhoid fever may have a grave prognosis. The quinolone group is perhaps the most effective in treating typhoid fever. Our patient received adequate ciprofloxacin and metronidazole treatment, yet she did not survive. Though blood culture and drug sensitivity were not carried out, there is sufficient evidence to show that quinolone resistance of Salmonella typhi is minimal.(5,6,7) It is also true however, that resistance to quinolones has been increasing.(8) The lesson we may learn from this report is that it is important not to compromise surgical intervention in a patient of typhoid fever who has developed features of peritonitis. In our patient, surgery was delayed because the patient was adjudged a poor risk as a result of the septic shock and acute renal failure that had developed. Although some reports have shown benefits of corticosteroids in severe Salmonella typhi toxaemia it is impossible to say if this measure might have been effective in our patient.(9) The main renal complications associated with typhoid fever are pyelonephritis, nephrotic syndrome and glomerulonephritis. The bilateral loin tenderness in this patient led us to make a presumptive diagnosis of pyelonephritis. The incidental finding of renal cell carcinoma instead of the suspected pyelonephritis is interesting though very likely of no significance. This case also illustrates the occult nature of renal cell carcinoma and its ability to assume massive proportions without manifesting the classical triad of haematuria, loin pain and frank mass. It must be emphasised that renal cell carcinoma occurs mainly between the sixth and eighth decades of life and rarely occur in adults younger than 40 years of age.(10) Young age at diagnosis, as in this patient, is characteristic of familial forms but only a small fraction of patients have an affected family member.(10,11 )Renal cell carcinoma was not high on our list of differential diagnoses in this patient considering her age and clinical profile which prevented reasonable objective assessment of her condition. This is not surprising given that two-thirds of renal cell carcinomas found in a series of patients studied at autopsy were not recognised clinically.10 Imaging procedures, such as CT or ultrasonographic scan of the abdomen usually facilitate the antemortem diagnosis of clinically silent renal cell carcinoma as was seen in this case. However the ultrasound suspicion of renal neoplasm was not absolutely considered in this patient because of the absence of corroborating evidence.(12,13,14 )This report also highlights the importance in considering non-infectious causes of fever particularly for physicians practising in tropical and sub-tropical countries. Most patients with cancer have fever at some time during the course of their illness. The fever may be related to concomitant infection, localised obstruction by the tumour, surgery and postoperative complications, or the neoplasm itself. Neoplasms that are most frequently associated with fever are Hodgkin’s lymphoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, leukaemia, hepatoma and renal cell carcinoma. Biopsy of accessible lymph nodes or organs remains the most definitive approach to investigate neoplastic causes of pyrexia of unknown origin while the importance of comprehensive history and meticulous physical examination cannot be overemphasised.

.jpg)

Fig.1: Segment of the ileum showing perforation and ulcers

Fig.2: Cut section through the left kidney and the upper pole mass

.jpg)

Fig.3: H & E histology section of the mass- renal cell carcinoma

REFERENCES

1. Otegbayo JA, Daramola OO, Onyegbutulem HC, Balogun WF, Oguntoye OO. Retrospective analysis of typhoid fever in a tertiary health facility. Trop Gastroenterol. 2002;23:9–12.

2. Lin FY, Vo AH, Phan VB, Nguyen TT, Bryla D, Tran CT, et al. The epidemiology of typhoid fever in the Dong Thap Province, Mekong Delta region of Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;62:644–8.

3. Olubuyide IO. Factors that may contribute to death from typhoid infection among Nigerians. West Afr J Med. 1992;11:112–5.

4. Otegbeyo JA. Typhoid fever: The challenges of medical management. Annals of Ibadan Postgraduate Medicine. 2005;3:602.

5. Alam MN, Haq SA, Das KK, Baral PK, Mazid MN, Siddique RU, et al. Efficacy of ciprofloxacin in enteric fever: comparison of treatment duration in sensitive and multidrug-resistant Salmonella. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:306–11.

6. Schwalbe RS, Hoge CW, Morris JG Jr, O’Hanlon PN, Crawford RA, Gilligan PH, et al. In vivo selection for transmissible drug resistance in Salmonella typhi during antimicrobial therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:161–3.

7. Stanley PJ, Flegg PJ, Mandal BK, Geddes AM. Open study of ciprofloxacin in enteric fever. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1989;23:789–91.

8. Rowe B, Ward LR, Threlfall EJ. Ciprofloxacin-resistant Salmonella typhi in the UK. Lancet. 1995;346:1302.

9. Hoffman SL, Punjabi NH, Kumala S, Moechtar MA, Pulungsih SP, Rivai AR, et al. Reduction of mortality in chloramphenicol-treated severe typhoid fever by high-dose dexamethasone. N Engl J Med. 1984;310:82–8.

10. Motzer RJ, Bander NH, Nanus DM. Renal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:865-75.

11. Mellemgaard A, Engholm G, McLaughlin JK, Olsen JH. Risk factors for renal cell carcinoma in Denmark. Role of socioeconomic status, tobacco use, beverages, and family history. Cancer Causes Control. 1994;5:105–13.

12. Hellsten S, Berge T, Wehlin L. Unrecognized renal cell carcinoma. Clinical and diagnostic aspects. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1981;15:269–72.

13. Porena M, Vespasiani G, Rosi P, Costantini E, Virgili G, Mearini E, et al. Incidentally detected renal cell carcinoma: role of ultrasonography. J Clin Ultrasound. 1992;20:395–400.

14. Konnak JW, Grossman HB. Renal cell carcinoma as an incidental finding. J Urol 1985;134:1094–6.