48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|1754

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Acute upper gastrointestinal bleed (AUGIB) is a common medical emergency encountered in clinical practice. The advances in medical practice in recent decades have influenced the management of AUGIB.

1 In studies done in Western population, as well as Southern and coastal India, peptic ulcer disease still constitutes the most common cause of upper gastrointestinal bleed.

2-5 Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy plays an important role in the diagnosis of etiology of bleed, stratification of patients according to the risk of rebleed based on the endoscopic stigmata and in treatment of such patients.

Various scoring systems have been proposed for assessment of risk of rebleeding and mortality in patients with AUGIB.

6 These include amongst others the clinical and endoscopic Rockall score, Glasgow Blatchford risk score (GBS) and AIM 65 score.6-9 GBS predicts the need for endoscopy and admission on basis of parameters like age, systolic blood pressure, hemoglobin, blood urea nitrogen and comorbidities.

7 AIM 65 is a simple bedside score which helps in predicting mortality using five factors including albumin levels, deranged INR, impaired mental status, SBP of 90 or less, age of 65 or more.

8 The Rockall score is used to predict mortality and consists of a pre-endoscopic clinical score and a complete endoscopic score after endoscopy.

5,9 While a number of studies are available from the Western population on the utility of these scores, the data from India is miniscule. We proposed to study the role of clinical and endoscopic Rockall scores in patients presenting with AUGIB at a large tertiary care center in India.

Materials and Methods

This study was prospectively conducted from January 2013 to May 2014. One hundred seventy-five patients who were admitted with AUGIB and underwent endoscopy in emergency medical services were enrolled in the study. An informed consent was obtained from all patients enrolled in the study. In the event of patient being critical and not able to give consent, the same was obtained from the closestrelative present with him. The study was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee.

The patients who were 18 years or above in age and presented with AUGIB were considered for inclusion. We excluded those who were pregnant or not willing to provide consent and who could not undergo endoscopy. All patients were initially stabilized with prompt intravenous access (central line/large bore intravenous cannula), volume resuscitation with crystalloids, blood transfusion, intravenous proton pump inhibitor and intravenous terlipressin 1mg (in suspected variceal bleeding) every 6 hours. The demographic data- age, sex, presentation with hematochezia, postural symptoms, alcohol abuse, intake of NSAIDS, anti-platelets, vitamin K antagonists, and history of AUGIB with history of previous comorbidities were recorded in a predesigned proforma. Haemoglobin, platelet count, coagulogram and liver function tests were obtained on admission. The clinical Rockall score was calculated using the clinical data at admission.

9 These patients underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy when they were hemodynamically stable (pulse rate <100 beats/min, systolic arterial blood pressure >100 mm Hg) and free from hepatic encephalopathy. Esophageal varices were graded using the Japanese Research Society for Portal Hypertension classification.

10 Patients with ulcer bleed were classified according to endoscopic appearance of lesion using Forrest classification system.

11 Patients underwent endoscopic therapy of choice at the discretion of the endoscopist. Complete Rockall score was then calculated incorporating the endoscopic findings in the clinical Rockall scoring calculated initially. According to the Rockall score, the points of 0, 1, 2 and 3 were assigned as per the parameters: age (<60 years: 0; 60–79 years: 1; >80 years: 2), hemodynamics (pulse <100/min and systolic blood pressure >100 mm Hg: 0; pulse >100/min and systolic blood pressure >100 mm Hg:1; pulse>100/min and systolic blood pressure<100 mm Hg: 2), co morbidities (none: 0; ischemic heart disease, cardiac failure, other major comorbidity: 2; renal or liver failure, disseminated malignancy: 3); endoscopic diagnosis (Mallory-Weiss tear or no lesion and no stigmata: 0; all other diagnosis: 1; malignant lesions of upper gastrointestinal tract: 2) and endoscopic stigmata of hemorrhage (no stigmata or dark spot on ulcer: 0; blood in upper gastrointestinal tract, adherent clot, visible or oozing or spurting vessel: 2).9 Details of medical management such as the number of transfused blood units, endoscopic diagnosis, therapeutic procedure done and duration of hospital stay were recorded. The outcomes measured in terms of rebleeding (recurrence 24 hours after initial endoscopy), need for surgery and mortality were recorded at 48 hrs following endoscopy. Patients were contacted 4 weeks after procedure either through telephone or through out-patient services to determine the outcome in terms of rebleeding, surgery and mortality. If the patient rebled, the therapy done and the outcome of the same were also recorded.

Statistical data is described in percentages for categorical variables and as the mean ± standard deviation values and ranges in case of continuous variables. The data was analyzed with parametric and non-parametric tests for determining statistical significance. For categorical data, comparisons were made by using the Chi-square/Fisher exact test, for quantitative data by test and for non-normally distributed quantitative variables by the Mann-Whitney/Kruskal Wallis test. A P value =0.05 was considered significant in all statistical evaluations. The clinical and complete Rockall score calculated were analyzed by considering the association with the outcome and multiple regression analysis was done to look for significant predictors of outcome. The usefulness of the scoring system in predicting outcomes was analyzed by calculating the area under receiver-operator curves.

Results

Clinical profile

Of the 175 patients of AUGIB who were prospectively studied, 138 (78.9%) patients were male and thirty-seven patients (21.1%) were female. The mean age of the patients enrolled was 48.4 ±16.4 years (range: 14 to 85 years). A total of 13 (7.4%) patients presented with hematochezia and 100 (57.1%) presented with postural symptoms on admission. Seventy-six (43.4%) patients were alcohol consumers in cirrhogenic doses while 30 (17.1%) were chronic smokers. Twenty four (13.7%) patients gave history of NSAID abuse, 3 (1.7%) were on chronic anticoagulation and 24 (13.7%) were on anti-platelets for ischemic heart disease or past cerebrovascular accident. Alcohol consumption in cirrhogenic doses was more common in patients with variceal bleed than in non-variceal bleed, being present in 61.3% (n=49) as compared to 29.7% (n=27)(p value <0.001). NSAID intake was significantly higher in patients with non-variceal bleed 18.7% (n=17) as compared to patients with variceal bleed 6.3% (n=5) (p=0.015). Anti-platelet intake was also significantly higher in patients with non-variceal bleed, 23.1% (n=21) as compared to variceal bleed 3.8% (n=3) (p value <0.001).

Of the fifty-six (32%) patients who had a history of AUGIB, variceal bleed had been diagnosed in 29 (52.7%), peptic ulcer in 9 (16.4%) patients. Of the 108 (61.8%) patients who had comorbidities, 68 (38.9%) patients had one long term comorbidity, 27 (15.4%) patients had 2 and 13 (7.4 %) patients had 3 comorbidities (Table 1). Eighty-eight (50.3%) patients required only one pRBC (packed red blood cell) transfusions while 60 (34.3%) patients received 2-4 and 27 (15.4%) patients received >4 transfusions. The most common etiology of AUGIB in our study was varices followed by peptic ulcer disease and mucosal erosions (Table 1). Variceal bleed was the most common cause of AUGIB in patients with CLD, being responsible for 81.1% cases (n=73), followed by peptic ulcer contributing to 7.8% (n=7). Rapid urease test was performed in 55(57.9%) patients of non-variceal bleed of which 29 (52.7%) tested positive for Helicobacter pylori. Overall chronic liver disease was present in 90 patients of whom 48 had previously recognized cirrhosis. Of the variceal bleeders, 73 had underlying cirrhosis while 7 had non-cirrhotic portal hypertension due to extrahepatic portal venous obstruction

Laboratory parameters

On admission, 57 (32.6%) patients had severe anemia with hemoglobin value of less than or equal to 7 g/dl and the mean hemoglobin of all patients was 8.63 ± 3.09 g/dL. The mean platelet count was 160.45 ± 117.06 x 103 cells/ cu.mm (median of 126.00 x 103 cells/ cu.mm and range of 118 - 640x 103 cells/ cu.mm). In patients with variceal bleed, as compared to those with non-variceal bleed, both the mean hemoglobin levels (7.66 ± 2.66g/dLvs 9.46 ± 3.23g/dL) and platelet counts (110 ± 95.9x 103 cells/ cu.mm vs 205 ± 117x 103 cells/ cu.mm) were lower at the time of admission. The mean blood urea was 60.90± 43.18mg/dl, serum creatinine was 0.98± 0.82mg/dl, bilirubin was 2.25± 3.48mg/dl and albumin was 3.53±0.59g/dl (median of 3.7g/dl and range of 2.0-5.1g/dl). The liver functions including bilirubin (3.76 ±4.37 and 1.00±1.72 md/dL), SGPT (72.95 ±95.24 and 30.85 ± 28.60 U/L) and SGOT (92.98 ± 92.44 and 31.71± 24.14 U/L) were higher in variceal bleeders while albumin (3.21 ±0.61 and 3.80 ±0.42, respectively) levels were significantly lower in variceal vis-à-vis the non-variceal bleeders.

Treatment and Outcome (Table 2)

Of the 80 patients who presented with variceal bleed 20 (25%) had grade I varices, 14 (17.5%) had grade II varices and 46 (57.5%) had grade III varices. Sixty-three (78.5%) patients underwent endoscopic therapy of which 57 (90.5%) patients underwent band ligation and 6 (9.5%) patients underwent sclerotherapy. Of the patients who presented with peptic ulcer bleed, 3 (7.1%) had Forrest grade Ia ulcer, 5 (11.9%) had Ib lesion, 5 (11.9%) had IIa lesion, 8 (19.1%) had IIb lesion, 4 (9.5%) had IIc lesion and grade III lesion was present in 17 (40.5%) patients. Seven (16.6% of peptic ulcer) patients were managed with adrenaline injection, 7 (16.6% of peptic ulcer) underwent hemostatic clipping and 2(4.7% of peptic ulcer) patients underwent multimodal therapy for endoscopic hemostasis.

Forty (22.9%) patients re-bled at 4 weeks, 35 (20%) patients died and surgery for control was done in 12 (6.9%) patients. All 12 patients who underwent surgery were in the non-variceal group, 10 had ulcer bleed while one each had pseudoaneurysmal and gastrojejunostomy site ulcer related bleed. In the subgroup of patients with variceal bleed, 22 (27.5%) patients re-bled at 4 weeks and 19 (23.8%) patients died and none underwent surgery. In patients with non-variceal bleed, 18 (18.9%) patients rebled at 4 weeks, 16 (16.8%) patients died and surgery for control of GI bleed was done in 12 (12.6%) patients. Of the five patients with non-varcieal bleeding who died because of rebleeding, two had peptic ulcer disease while three had underlying malignancy.

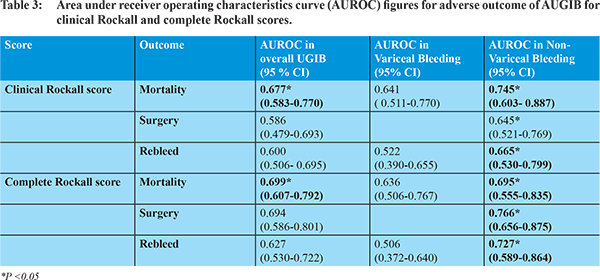

Utility of clinical and complete Rockall score and predictors of outcome (Table 3)

Area under ROC was calculated for each of the outcome in both clinical and complete Rockall scores. The clinical Rockall score was not effective in predicting the need for surgery (AUROC= 0.586, 95% CI: 0.479- 0.693, p=0.321) or rebleed (AUROC= 0.600, 95% CI: 0.506- 0.695, p-0.055), however it was effective in predicting mortality (AUROC= 0.677, 95% CI: 0.583- 0.770, p= 0.001). The complete Rockall score performed much better than the clinical Rockall score in predicting the outcome in terms of rebleed (AUROC= 0.627, 95% CI: 0.530- 0.722, p value 0.016), need for surgery (AUROC= 0.694, 95% CI: 0.586- 0.801, p= 0.025) and mortality (AUROC= 0.699, 95% CI:0.607- 0.792, p= 0.000). We also compared the two scores for predictors of outcome in the subgroups of non-variceal and variceal bleed and this is presented in table 3.

Univariate analysis found that the factors associated with increased risk of mortality in patients undergoing AUGIB were age = 65 years, signs of liver cell dysfunction, blood transfusion > 2 units, blood urea > 50 mg/dl, serum bilirubin = 3 mg/dl and serum albumin< 3g/dl. Consequently, a multivariate analysis done showed increased mortality in patients with age = 65 years (adjusted OR: 9.5, 95% CI: 3.108- 29.266) and in patients with albumin <3 g/dl (aOR: 3.1, 95% CI: 1.049- 9.682). The mortality rates for each clinical and complete Rockall score are provided as table 4A and 4B.

Discussion

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding is a common gastroenterological emergency and there is a need to stratify these patients so that appropriate care can be provided. Various scoring systems have been advocated for pre-endoscopy assessment and for post-endoscopic prognostication.

6-9 There is only limited literature from India about utility of these scores. The present paper focuses on utility of clinical and complete Rockall score for assessing risk of rebleeding and mortality.

In our 175 patients, variceal bleeding was the most common cause of bleeding. This is consonance with some reports from North India but in other reports peptic ulcer disease remains the commonest cause.

4,5,12 Interestingly, some patients with variceal bleeding had small varices (grade I) which could be due to use of drugs like terlipressin and reduction of size after gastrointestinal bleeding.

Use of clinical Rockall score involves assessment of age, presence of comorbidities, presence of shock and tachycardia and can be measured at the bedside and at first assessment of the patient. Therefore, it may help in stratifying the risk at the initial stage and direct specialized care including ICU transfer and very early endoscopy to the subgroup which most needs the intervention.

9 After endoscopy, the diagnosis and the endoscopic findings further help in stratification of the patients. The utility of the score lies in the fact that no additional investigations are warranted except the usual care needed in these patients. Our results suggest that clinical and complete risk scoring system developed by Rockall et al is a useful tool for stratifying patients with AUGIB into high and low risk categories for mortality. However, for the prediction of rebleed and surgery, the complete Rockall scoring system was found to be better than the clinical scoring system. This scoring system performed much better in predicting the outcomes in non-variceal bleed than in patients with variceal bleed. The mortality rates in our population for clinical Rockall score (6.5% for score of 0 and 66.7% for score of 7) are similar to those obtained by Rockall et al (mortality of 2.4% for Score of 0 and 50% for a score of 7).

9 Similar results were also obtained for complete Rockall score in our population (mortality of 0 for a score of 0 and 33.3% for a score of 8 or more) vis-à-vis the original study (0 for score of 0 and 41% for a score of 8 or more). The disappointing performance of the risk scoring system in the prediction of rebleeding and surgery in our study and several similar studies might be partly explained by the fact that the risk scoring system was originally developed for the prediction of mortality.

13,14 In patients with non-variceal bleed both the clinical and complete Rockall score were effective in predicting mortality. In predicting rebleed, the complete Rockall score performed much better than the clinical Rockall score in these patients.

However, in patients with variceal bleed these scores were not that effective in predicting outcomes. Only few studies have compared the efficacy of this scoring system in the subgroups of patients with variceal and non-variceal bleed. These reports also indicate that the Rockall score was predictive of both rebleeding and mortality in patients with variceal bleed to a lesser degree when compared to patients with non-variceal bleed.

14-16 Even other scores like GBS may not perform as well in the setting of variceal bleeding.

16 The limitations of the present study include the fact that it is a single center studydone at a large tertiary care center which may not represent the usual clinical strata dealt at first referral institutions. Also, the study used only one clinical score and therefore no comparison is available with other scores in use. However, the study is important as it is the first prospective study assessing Rockall score in Indian patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding showing that the score can be used to stratify patients with AUGIB and is more useful in non-variceal bleeding.

References

- Gralnek IM, Dumonceau JM, Kuipers EJ et al. Diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy. 2015;47:a1-46.

- Boonpongmanee S, Fleischer DE, Pezzullo JC et al. The frequency of peptic ulcer as a cause of upper-GI bleeding is exaggerated. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:788-94.

- Wollenman CS, Chason R, Reisch JS et al. Impact of ethnicity in upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:343-50.

- Simon EG, Chacko A, Dutta AK et al. Acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding-experience of a tertiary care center in southern India. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2013;32:236-41.

- Singh SP, Panigrahi MK. Spectrum of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in coastal Odisha. Trop Gastroenterol. 2013;34:14-7.

- Simon TG, Travis AC, Saltzman JR. Initial Assessment and Resuscitation in Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2015;25:429-42.

- Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet. 2000;356:1318-21.

- Saltzman JR, Tabak YP, Hyett BH et al. A simple risk score accurately predicts in-hospital mortality, length of stay, and cost in acute upper GI bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1215-24.

- Rockall TA, Logan RF, Devlin HB et al. Risk assessment after acute upper gastro-intestinal haemorrhage. Gut. 1996;38:316-21

- Beppu K, Inokuchi K, Koyanagi N et al. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage by esophageal endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1981;27:213-8.

- Laine L, Stein C, Sharma V. A prospective outcome study of patients with clot in an ulcer and the effect of irrigation. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;43:107-10.

- Anand CS, Tandon BN, Nundy S. The causes, management and outcome of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in an Indian hospital. Br J Surg. 1983;70:209-11.

- Custodio Lima J, Garcia Montes C, KibuneNagasako C et al. Performance of the Rockall scoring system in predicting the need for intervention and outcomes in patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a Brazilian setting: a prospective study. Digestion. 2013;88:252-7.

- Vreeburg EM, Terwee CB, Snel P et al. Validation of the Rockall risk scoring system in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gut. 1999;44:331-5

- Jairath V, Rehal S, Logan R et al. Acute variceal haemorrhage in the United Kingdom: patient characteristics, management and outcomes in a nationwide audit. Dig Liver Dis. 2014;46:419-26.

- Thanapirom K, Ridtitid W, Rerknimitr Ret al. Prospective comparison of three risk scoring systems in non-variceal and variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Oct 30. doi:10.1111/jgh.13222.