48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|1771

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Choledochal cysts are congenital bile duct anomalies with cystic dilatation of the biliary tree. The incidence is approximately 1 in 150,000 births in the West. The disease is however more common in the east and presents later since antenatal diagnosis and early access to tertiary care is often delayed.

1,2 The surgical management entails a complete excision of the cyst followed by re-establishment of the biliary drainage - done by two commonly established procedures. i] a direct anastomosis of the bile duct to the second part of duodenum - hepatico-duodenostomy (HD) or ii] a Roux-en-Y anastomosis of the bile duct to jejunum in a Y fashion - Hepatico-jejunostomy (HJ).

There are a few retrospective studies that compare the outcomes between these two surgical technique.

3,4 Narayan et al published a systematic review of the six retrospective trials that compared HD and HJ anastomosis. Most of the trials had small numbers and none were randomised.

5 The authors concluded that there were ‘few good quality studies’ andoutcomes of the two procedures were comparable. They however asserted that ‘caution needed to be exercised’ before results of their systematic review were generalized.

Our study followed up patients who had surgery for choledochal cyst in a single tertiary care teaching institution. The operating surgeon was free to choose either of the two anastomosis (HD and HJ) to restore biliary continuity. We studied the early and intermediate complications.

Patients and Methods

Study design and sample size

Aretrospective observational cohort study was undertaken of children who presented with choledochal cysts between June 2007 and Jan 2014. Two cohorts depending on the type of anastomosis done to restore biliary continuity were analysed (HD and HJ). The sample size of 35 patients per arm was calculated to show significant difference between the complication rates of the two arms based on previously published literature.

Patients

Consecutive patients who presented to the Department of Paediatric Surgery with type 1 and 4 choledochal cysts were included in the study. Children who underwent a laparoscopic hepatobiliary anastomosis and those who were treated by other modalities – such as the Lilly’s procedure (6), drainage of cysts and a jejunal conduit were excluded from the study.

Operation

The operation was performed by or under the supervision of a qualified paediatric surgeon in a tertiary care medical college. The operating surgeon was free to choose either of the two anastomosis (HD and HJ) to restore biliary continuity. HD was performed by an end biliary anastomosis to the post-pyloric duodenum that could be safely mobilized to the common hepatic duct (approximately 2.5 cm from the pylorus).7 The HJ anastamosis was performed by a creation of a Roux limb that was 15 to 20 cm long. The biliary enteric anastomosis was end to side using 4-0 Vicryl (polygalactin 910) sutures in both methods.

Outcome variables

We sought to study the early and intermediate complications. The primary outcome variables recorded were bile leak, pancreatic leak, intestinal obstruction, pancreatitis, cholangitis, jaundice, abscesses or inter loop collections and wound infection. Secondary outcomes recorded were stricture, malignancy and need for any second procedure. Symptoms such as biliary gastritis were assessed clinically and were advised an endoscopy if indicated.

Statistical methods

The collected data was entered in an MS Excel sheet and then analysed using SPSS 16.0 software (Chicago, SPSS Inc.). Statistical significance was determined using the t test. A p-value < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

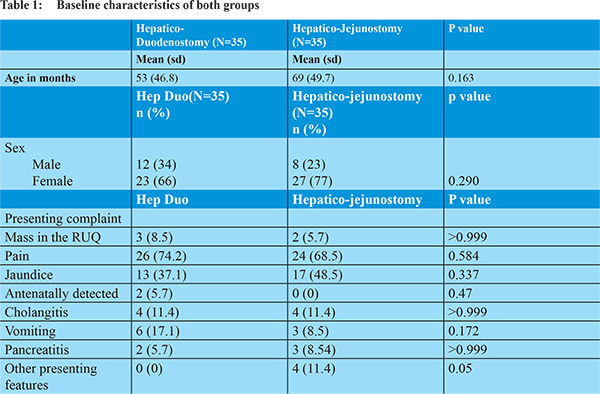

The two patient groups were comparable in their baseline characteristics (Table 1). The ratio of male to female in our population was 1:2.5. There was no difference in the clinical presentations between the two cohorts. Four children (5.7%) in the HJ group had unusual presentation: (1) A child had a CBD rupture in infancy and later presented with a choledochal cyst; (2) A child presented with a perforation of the choledochal cyst with biliary peritonitis; (3) A laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed on a young girl at another centre that had missed the choledochal cyst and the child continued to have abdominal pain; (4) A child with stones in the bile duct had a forme fruste cyst and was initially managed with ERCP and stenting. This child’s parents specifically requested a HJ.

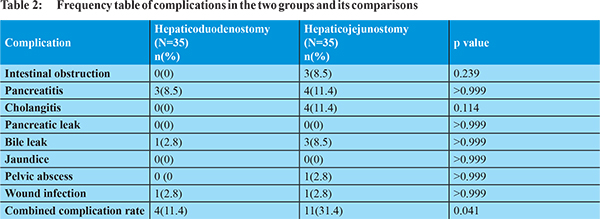

Three children (8.5%) had intestinal obstruction and 4 (11.4%) had cholangitis in the HJ group. These complications were not seen in the HD group. Three children (8.5%) had a bile leak in the HJ group when compared to 1 child (2.8%) in the HD group. One child (2.8%) in the HD developed a stricture at the anastomosis that required revision a year later. Other complications are listed in Table 2. The individual complication rates between the two groups were not statistically significant.However when all complications were combined, the chance of having a complication in the HJ group was significantly higher than the HD cohort (p value 0.041).Hospital stays between the two groups were comparable with a median stay of 6 days (IQR 6 to 8 days) for the HD group and 7 days (IQR 6 to 9 days) for the HJ group. The difference in the length of stay in both groups was not statistically significant. The median follow up of 17.5 months (IQR 13 to 31 months) in the HD group and 18 months (IQR 6 to 31 months) in the HJ group. The duration of follow up was adequate for a short to medium term complication assessment, though not ideal to pick up later complications such as strictures and malignancy.

Discussion

The standard of care for the surgical management of choledochal cysts is complete excision and reconstruction of biliary drainage via either the duodenum (hepatico-duodenostomy) or the jejunum (Roux-en-Y). Few papers compare the outcomes of these two procedures. Both forms of reconstruction are performed routinely in our institution. Many of the other teaching institutions in the Indian subcontinent routinely construct either one form of biliary enteric drainage alone making a similar comparison at a multicenteric level difficult.

8,9 Both cohorts in our study had comparable baseline characteristics. However 4 children as discussed, had unusual presentations. These children underwent HJ creating a potential bias. This can be avoided by prospectively randomizing patients in future trials.

HJ has been historically troubled by intestinal obstruction as the major complication. This can be easily understood as the infracolic compartment is accessed and the Roux-en-Y limb passes through the transverse mesocolon. Three children in the HJ arm in our series had intestinal obstruction. Though the difference is not significant, it is worth noting that there were no children who had bowel obstruction after they underwent HD. HD has the advantage of having the dissection and anastomosis limited in the supra-colic compartment and hence less adhesions or internal herniation. Further at follow up, HD offers easy endoscopic access for stone extraction and dilatation of strictures. No child in this series required any endoscopic intervention. The one child who developed a stricture after HD was explored by laparotomy and found to have a tight wrap of omentum causing the anastomotic stricture. This was managed by a reconstruction of the HD. Our series did not include any patients who underwent laparoscopic repair. However those who do laparoscopic choledochal cyst surgery in our institution find HD technically easier. There are many who create the Roux – en Y hepatico jejunostomy laparoscopically as well.

10-12 A similar study by Santore and colleagues had a smaller group of patients and included laparoscopic repairs in their cohorts.

4 This cohort had a single stricture in their follow up as well and this was in the HJ group. They concluded that the HD is a better operation as it was a faster operation, required less bowel recovery times and produced fewer postoperative complications that needed reoperation.

There is often a worry of bile gastritis. We found none of our patients had clinically significant bile gastritis. Two papers that are commonly cited with reference to bile gastritis are by Shimotakahara et al

3 and Takada et al.

13 None of the patients in the latter study had any clinical symptoms of bile reflux. The endoscopic findings of gastric erosions and bile seen refluxing through the pylorus was taken as positive for bile reflux gastritis. The long term significance of this is still unclear.

The early and the late complications in our cohort was similar in both the groups. However, when collectively examined it seems to favour the HD construct. Though there seems to be a benefit with the HD construct the numbers are not adequate to achieve significance, and may be better served by a larger multicenteric randomised controlled trial. Limitations of such a cohort study lie in the ability of the surgeon to choose the biliary drainage conduit. Our series suggests that when faced with a difficult anatomy or presentation the HJ Roux en Y is the preferred biliary drainage in view of its versatility.

References

- Lipsett PA, Pitt HA, Colombani PM, Boitnott JK, Cameron JL. Choledochal cyst disease. A changing pattern of presentation. Ann Surg. 1994;220(5):644-52.

- O’Neill JA. Choledochal cyst. Curr Probl Surg. 1992;29(6):361-410.

- Shimotakahara A, Yamataka A, Yanai T, Kobayashi H, Okazaki T, Lane GJ, et al. Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy or hepaticoduodenostomy for biliary reconstruction during the surgical treatment of choledochal cyst: which is better? Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;21(1):5-7.

- Santore MT, Behar BJ, Blinman TA, Doolin EJ, Hedrick HL, Mattei P, et al. Hepaticoduodenostomy vs hepaticojejunostomy for reconstruction after resection of choledochal cyst. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(1):209-13.

- Narayanan SK, Chen Y, Narasimhan KL, Cohen RC. Hepaticoduodenostomy versus hepaticojejunostomy after resection of choledochal cyst: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(11):2336-42.

- Lilly JR. The surgical treatment of choledochal cyst. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979;149(1):36-42.

- Liem NT, Pham HD, Dung LA, Son TN, Vu HM. Early and Intermediate Outcomes of Laparoscopic Surgery for Choledochal Cysts with 400 Patients. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2012;22(6):599-603.

- Poddar U, Thapa BR, Chhabra M, Rao KL, Mitra SK, Dilawari JB, et al. Choledochal cysts in infants and children. Indian Pediatr. 1998;35(7):613-8.

- Chand K, Bhatnagar V, Agarwala S, Srinivas M, Das N, Singh MK, et al. The incidence of portal hypertension in children with choledochal cyst and the correlation of nitric oxide levels in the peripheral blood with portal pressure and liver histology. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg. 2015;20(3):133-8.

- Chokshi NK, Guner YS, Aranda A, Shin CE, Ford HR, Nguyen NX. Laparoscopic choledochal cyst excision: lessons learned in our experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19(1):87-91.

- Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Parthasarathi R, Amar V, Senthilnathan P. Laparoscopic management of choledochal cysts: technique and outcomes-a retrospective study of 35 patients from a tertiary center. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;207(6):839-46.

- Yeung F, Chung PHY, Wong KKY, Tam PKH. Biliary-enteric reconstruction with hepaticoduodenostomy following laparoscopic excision of choledochal cyst is associated with better postoperative outcomes: a single-centre experience. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015;31(2):149-53.

- Takada K, Hamada Y, Watanabe K, Tanano A, Tokuhara K, Kamiyama Y. Duodenogastric reflux following biliary reconstruction after excision of choledochal cyst. Pediatr Surg Int. 2005;21(1):1-4.