48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|2961

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Megacolon is defined as greater than 6.5 cm diameter of the rectosigmoid region or descending colon on abdominal plain film; an ascending colon diameter of greater than 8 cm; or a caecal diameter greater than 12 cm1. Acquired megacolon has a variety of causes, notably thyroid dysfunction, medications (anti-psychotic drugs), Chagas disease, diabetic neuropathy, spinal cord injury and scleroderma. It can also occur as a result of colonic compression due to anterior sacral masses like a sacral meningocele.The Currarino triad consists of partial sacral agenesis, anorectal stenosis and a presacral mass. About 50% of cases are familial with autosomal dominant inheritance2. We report a case of acquired megacolon due to anterior sacral meningocele causing local pressure effect on the colon and intestinal obstruction in association with sacral defects and an anorectal stricture. These features are a part of a relatively uncommon condition called the Currarino syndrome.

Case Report

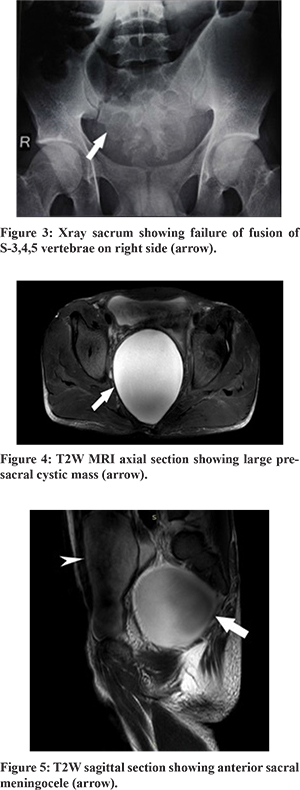

A 27-year-old male patient was admitted in the Department of Gastroenterology Sawai Man Singh Hospital with complaints of constipation and abdominal fullness with visible loop of peristalsis since childhood. He also complained of bleeding per rectum for the last 6 months. The patient was born out of a non-consanguineous marriage at full term by an uncomplicated vaginal delivery at home. There was no history suggestive of birth asphyxia or trauma. The patient was prescribed laxatives, enemas and other conservative measures for constipation. However, his symptoms were persistent. Physical examination of the abdomen did not reveal any abnormality. Rectal examination was painful with resistance felt 2 cm beyond the anal verge and the finger crossed that area with moderate resistance. Examination of the spine at the back did not show any bony defects. There was no neurological deficit. Hemogram showed severe microcytic hypochromic anemia with normal liver function tests, renal function tests, thyroid function tests and serum electrolytes. X-ray sacrum revealed failure of fusion of the S3,4,5 vertebrae on the right side.Barium enema showed a dilated sigmoid colon (Figure 1). Ultrasound abdomen showed cystic lesions in the pelvis and horseshoe kidney. An MRI pelvis showed a presacral thin-walled clear fluid cyst communicating with the sacral cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) space measuring 101x93x95 mm pushing the rectum anteriorly with no restricted diffusion on diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) (Figure 2). There was no evidence of hydroureteronephrosis. Colonoscopy revealed concentric narrowing just above the anal verge with dilated rectum and colon. The patient was transferred to the neurosurgery Department for further management.

Discussion

Anterior sacral meningocoele (ASM) refers to a diverticulum of the thecal sac that protrudes anteriorly into the presacral space through a defect in the sacrum. The scimitar sacrum is the most common of the sacral anomalies. Most anterior sacral meningocoeles are sporadic.2

ASMs may be associated with anorectal malformations and sacral bony defects as in Currarino syndrome; or with Marfan’s syndrome wherein it is caused by a disorder of collagen biosynthesis and structure at the dural level.3

The most frequent findings of the triad include a sacrococcygeal defect, which may be categorised as total sacral agenesis or a partial asymmetric deformity. A presacral mass is another component of the triad. The masses that can present in this fashion are anterior meningoceles (most frequent), teratomas, enteric cysts, dermoid or epidermoid cysts, lipomas, hamartomas, and rectal duplications. Anorectal malformations are the third characteristic components of the triad and include anorectal stenosis with or without a blind ending fistula, anal atresia or ectopia, imperforate anus, and cloacal anomalies. Other manifestations include urogenital system malformations such as horseshoe kidneys, sigmoid kidneys, single pelvic kidney, neurogenic bladders, multicystic kidneys, vesicouretral reflux, and partial or complete duplication of the vagina, clitoris, or uterus.4

Clinically, these lesions have no gender predilection in childhood; however, a female preponderance is seen in adults. The lesion may remain asymptomatic or may manifest with nonspecific symptoms such as constipation and urinary or reproductive symptoms due to local pressure. A child with constipation due to this condition may be treated with laxatives for prolonged periods or be misdiagnosed with Hirschsprung’s disease. This can be avoided by performing a digital rectal examination, whose importance is often undervalued. Pressure on nerve roots may lead to sciatica, decreased detrusor and rectal tone and paraesthesias in the lower sclerotomes. Meningitis is a rare but important complication usually occurring secondary to iatrogenic manipulation of the sac or more infrequently, due to pressure erosion of the anterior sacral meningocoele into the rectum.

Radiological investigations include plain and contrast radiographs, ultrasound, computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). ‘Scimitar’ sign, a smooth curved unilateral sacral defect simulating shape of Arabic sabre on plain X-ray, is considered to be pathognomonic for ASMs.2

Ultrasound reveals uni or multilocular cysts – a high index of suspicion should be maintained in such cases in order to avoid the disastrous consequences of cyst manipulation. Computed tomography (CT) is useful to visualize both the sacral agenesis component as well as the cyst and associated tumor, if any. Pelvic and spinal MRI is mandatory for evaluation of the presacral mass. Additionally, it also detects associated intraspinal anomalies.

Surgical treatment of the presacral mass may require a posterior sagittal approach or a sacral laminectomy. An anterior abdominal approach may be used when the presacral mass is too large. The posterior sagittal approach with or without anorectoplasty has been reported as the best method of treating anorectal malformations with simultaneous excision of the presacral mass. For an anterior sacral meningocele, dural ligation of the neck of the meningocele is generally performed. Conservative treatment may be considered only in small lesions in males with no associated tumors.5

References

- Amy E. Foxx-Orenstein. Ileus and pseudoobstructionIn: Sleisenger and Fordtrans. Gastrointestinal and liver diseases. 10th ed. Elsevier ;2016.pp.2194

- Thomas P. Naidich, Susan I. Blaser, Bradley N. Delman, David G. Mclone et al. Congenital anomalies of the spine and spinal cord: Embryology and malformations, In Scott W. Atlas, Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain and Spine, 3rd Ed. Lipincott Williams and Wilkins 2002 : 1593-1595

- North RB, Kidd DH, Wang H. Occult, bilateral anterior sacral and intrasacral meningeal and perineurial cysts: Case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:981–6

- Kurosaki M, Kamitani H, Anno Y, Watanabe T, Hori T, Yamaski T. Complete familial Currarino triad. Report of three cases in one family. J Neurosurg 2001; 94:158–161

- K.Stuart Lee, David J Gower, Joe M Mcwhorter, David A Albertson.The role of MRI in the diagnosis and treatment of anterior sacral meningocoele,,Journal of Neurosurgery,1988;69:628-631.