|

Ira Shah, Nikita Magdum, Naman S. Shetty Department of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Hepatology, B J Wadia Hospital for Children, Mumbai, India.

Corresponding Author:

Dr Ira Shah Email: irashah@pediatriconcall.com

Abstract

Aim: Liver fibrosis and cirrhosis commonly occurs in patients with biliary atresia (BA). Liver biopsy is the gold standard for evaluating liver fibrosis; however it is invasive and may result in life-threatening complications. A safe and simple alternative to assess liver fibrosis in patients with chronic liver diseases is the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI). Patients and Methods: Newly diagnosed BA between May 2009 to March 2015, who underwent the Kasai procedure were included. APRI was calculated for all patients. Liver biopsy was done, and histopathologic analyses were performed using the Metavir classification. Results: Thirty-five patients (12 boys, median age of 1.9 months) were enrolled. Metavir scores were F4 in 13 patients,, F3 in 11, F2 in 11, and F1 in 0. The areas under the receiver operating characteristics curves for F3 and F4 were 0.92 and 0.91, respectively. Distinct optimal cut-off values of APRI for F3 and F4 were obtained (1.01 and 1.41, respectively). With an APRI of 1.57, the sensitivity and specificity to detect fibrosis were 48% and 52.17% respectively. With an APRI of 1.75, the sensitivity and specificity to detect cirrhosis were 50% and 57.14% respectively. Conclusion: APRI is not an effective tool to measure fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with biliary atresia in Indian children.

|

48uep6bbphidcol2|ID 48uep6bbphidvals|2991 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Introduction

Biliary atresia (BA) is a cholangio-destructive disease of both intra and extrahepatic parts of the biliary system which leads to cirrhosis and ultimately liver failure and remains the commonest indication for pediatric liver transplantation throughout the Western world. The incidence of BA is higher in Japan, China and probably south Asia (~1 in 8-9000 live births) than in Europe and the USA (~ 1 in 12 - 15000 live births)1,2. The histological appearance of the liver is characterised by a small cell infiltrate, portal tract inflammation, bile ductule plugging and proliferation ultimately leading to bridging fibrosis giving way to features of overt biliary cirrhosis. BA need surgical correction and early surgery (within 8 weeks) is extremely important for successful bile drainage and prolonged survival3,4,5,6,7. BA is the main cause of liver fibrosis in children, followed by viral chronic Hepatitis C and Chronic Hepatitis B, autoimmune hepatitis, cystic fibrosis and metabolic disease. The common end point of progressive fibrinogenesis is cirrhosis; however, the aetiology of liver disease changes the pattern of fibrotic development8,9. Liver biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosis of liver fibrosis. However, liver biopsy is difficult to use as a follow-up tool as it is an invasive procedure. The accuracy of liver biopsy is not fool proof due to intra-observer and inter-observer variability, which lead to an overstaging or understaging of fibrosis10. Thus, accurate evaluation of regression or progression of liver fibrosis by non-invasive methods is required. There are some non-invasive methods like fibroscan, fibro index, FIB-4, forns index, magnetic elastography, heap score, APRI index11. A study by Kim et al showed that Aspartate transaminase to platelet ratio index (APRI) can be used as tool for assessing liver fibrosis without additional risks in patients with BA during postoperative follow-up care11. APRI has already been validated to detect fibrosis in patients with hepatitis C12. This study aimed to validate use of APRI in the determination of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis in BA patients and its correlation with Metavir Index on liver histology.

Material and Methods

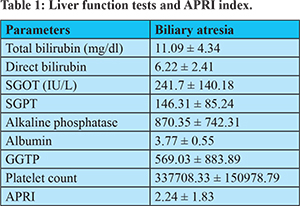

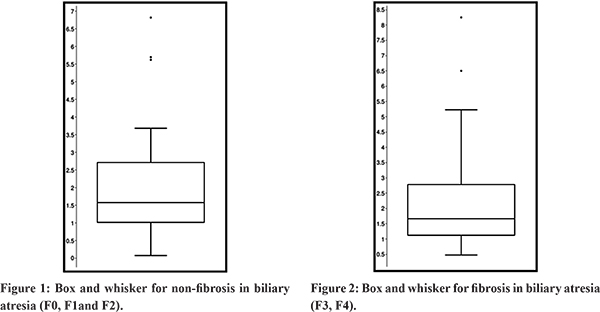

We conducted this retrospective study at the Pediatric Liver Clinic in Bai Jerbai Wadia hospital for children, Parel, Mumbai after ethics committee approval. All infants from 2009-2015 who were diagnosed to have BA on the basis of intra-operative cholangiogram (IOC) and liver biopsy were included in the study. Patient who were diagnosed to have etiologies other than BA on liver biopsy were excluded from the study. Patients with recent acute febrile illnesses, which could affect AST levels and platelet counts, were excluded from this study. Patients without AST or simultaneous platelet count during liver biopsy were also excluded from the study. Hemogram and liver function tests at the time of liver biopsy were used to calculate APRI index. An experienced pathologist reviewed the liver biopsy specimens. METAVIR score was used by the pathologist categorize the liver fibrosis as F0- no fibrosis; F1- portal fibrosis without septa; F2- portal fibrosis with few septa; F3- numerous septa without cirrhosis; and F4- cirrhosis13. At the time of liver biopsy, demographic data such as sex and age in months were noted. The biochemical parameters included serum AST, alanine aminotransferase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, alkaline phosphatase, total bilirubin, albumin, direct bilirubin, platelet count, and prothrombin time. The APRI was calculated as12:APRI= AST level/Upper normal limit for AST Platelet count (103 /L) X 100. Normal value of AST ranged from 5 to 40 U/L. Statistical Analysis: Distributed data were presented as the mean (SD); factors associated were analysed by the test and proportions by the x2 test. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curves were used to assess the diagnostic performance of the APRI. All of the cut-off values are associated with the probability of a true positive (sensitivity) and a true negative (specificity). The ROC curve plots sensitivity versus 1-specificity for all of the possible cut-off values.The area under ROC curve is the most commonly used accuracy index; values near 1.0 indicate high diagnostic accuracy. Thus, ROC curves were constructed for the detecting cirrhosis and Metavir fibrosis stage 3 or greater. Optimal cut-off values for APRI were chosen to obtain 95% specificity, or to obtain 95% sensitivity according to the diagnostic question. MedCalc software package version 7.2 for Windows® (MedCalc) was used for all statistical analyses. A p value <0.05 (2-tailed) was considered statistically significant. We plotted Box and whisker diagram of the APRI in relation to the Metavir fibrosis score. The box represents the interquartile range, the whiskers indicate the highest and lowest values, and the asterisks represent the outliers. The line across the box indicates the median value. This box was plotted for fibrosis versus non fibrosis that is F0, F1, F2 with F3, F4 and cirrhosis versus non cirrhosis this is F0, F1, F2, F3 with F4.

Results

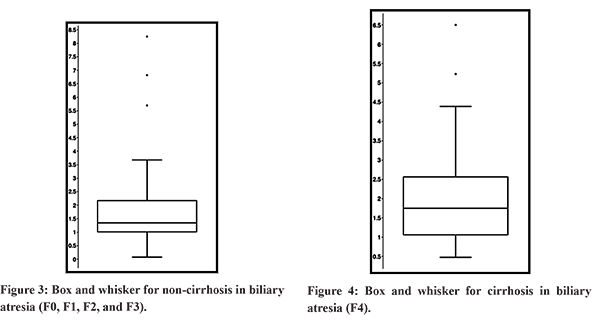

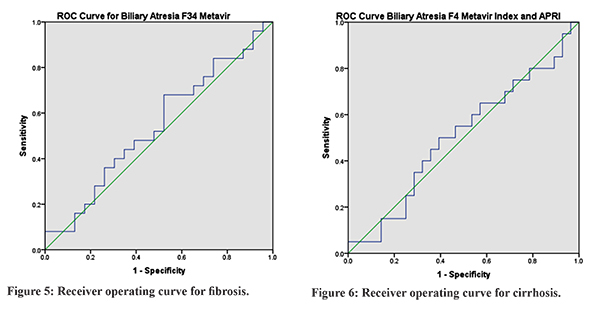

Forty-eight patients were diagnosed to have BA. Mean age of presentation was 2.8 ± 1.2 months. Male:female ratio was 23:25. The distribution of Metavir Index for F0, F1, F2, F3, F4 was 10 (20.83%), 10(20.8%), 3(6.25%), 5(10.41%), 20 (41.66%) respectively. Liver function tests and APRI index are depicted in Table 1. Box and whisker diagram of the APRI in relation to the Metavir fibrosis score for BA was plotted for non-fibrosis versus fibrosis that is F0, F1, F2 with F3, F4 and non-cirrhosis versus cirrhosis that is F0, F1, F2, F3 with F4 (Figure 1-4). Median and mean APRI for fibrosis was 1.67 and 2.3±1.9 and non-fibrosis was 1.57 and 2.15 ± 1.73 respectively. For non-cirrhosis median and mean was 1.34 and 2.02±1.84, and for cirrhosis was1.75 and 2.12±1.56 respectively.With an APRI of 1.57, the sensitivity and specificity to detect fibrosis was 48% and 52.17% respectively. With an APRI of 1.75, the sensitivity and specificity to detect cirrhosis was 50% and 57.14% respectively. Receiver operating curve (ROC) for biliary atresia for both fibrosis and cirrhosis is depicted in Figure 5 and 6. Area under curve for fibrosis was 0.541 with p value of 0.456. Area under curve for cirrhosis was 0.505 with p value of 0.456.

Discussion

The prognosis of chronic cholestatic diseases depends, on the extent of fibrosis in the liver14,15. It is not possible to do serial liver biopsies to assess the degree of fibrosis16-18.Fibrosis is distributed heterogeneously within the liver parenchyma. With Metavir scoring system, only 75% of biopsy specimens are classified correctly in terms of stage of fibrosis19. There is a difference of at least 1 stage of fibrosis between the right and left lobes in 33-45% of patients in various studies20,21,22. APRI is a non-invasive index of hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis and has been validated in a cohort of 270 patients with chronic hepatitis C virus; the areas under the ROC curves for significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in the training and validation cohort were 0.80 to 0.88 and 0.89 to 0.94, respectively12. The APRI classic cut-off values are validated for special populations such as chronic hepatitis C patients, but not for BA. Furthermore, hepatic fibrosis in BA may differ from fibrosis in hepatitis C. De Le´dinghen et al23 showed that there was a significant correlation of APRI to Metavir fibrosis scores in children with chronic liver diseases, including BA. Kim et al11 determined the reliability and accuracy of the APRI, in BA patients at the time of the Kasai portoenterostomy, in assessing fibrosis and histopathologic stage. Our study shows significant positive correlation between the fibrosis stages in Metavir F3 fibrosis or greater cirrhosis and APRI. Significant areas under the ROC curves for F3 were 0.92 and F4 was 0.91. In this study, in BA we had median APRI of 1.57 with sensitivity and specificity of 48% and 52.17% respectively for fibrosis group. And for cirrhosis group we got APRI median of 1.75 with sensitivity and specificity of 50% and 57.14%. In our study, we found that APRI index was not reliable to document liver fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with BA as seen by the area under the curve on ROC figures. This may be due to various reasons. This being the first study in Indian children, it may suggest ethnic variation. Also, most patients with biliary atresia were already having cirrhosis by the time they presented to us but did not have marked changes in the biochemical parameters namely SGOT and platelet count which may not reflect the amount of fibrosis or cirrhosis in these patients. Our study was a one-time cross-sectional analysis. We have not repeated liver biopsies again in these patients nor estimated APRI at the time of second liver biopsies to comment on the correlation over a period of time. Metavir Index though used universally is known to have variation of staging in various studies23 and hence co-relation with APRI may not be upto the mark.

Conclusion

APRI is not an effective tool to measure fibrosis or cirrhosis in patients with biliary atresia in Indian children.

References - Nio M, Ohi R, Miyano T, Saeki M, Shiraki K, Tanaka K. Five and 10-year survival rates after surgery for biliary atresia: a report from the Japanese Biliary Atresia Registry. J Pediatr Surg 2003; 38: 997-1000.

- McKiernan PJ, Baker AJ, Kelly DA. The frequency and outcome of biliary atresia in the UK and Ireland. Lancet 2000; 355: 25-29.

- Mowat AP, Psachorapoulos HT, Williams R. Extrahepatic biliary atresia versus neonatal hepatitis. A review of 137 prospectively investigated infants. Arch Dis Child 1976,51:763-770.

- Mieli-Vergani G, Portmann B, Howard ER, Mowat AP. Late referral for biliary atresia - missed opportunities for effective surgery. Lancet 1989, i: 421-423.

- Ohi R, Manamatsu M, Mochizuki I, Chiba T, Kasai M. Progress in the treatment of biliary atresia. World J Surg 1985, 9: 285- 293.

- Ohkohchi N, Chiba T, Ohi R, Mori S. Long-term follow-up study of patients with cholangitis after successful Kasai operation for biliary atresia: Selection of recipients for liver transplantation. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 1989, 9: 416- 420.

- Houwen RH, Zwierstra RP, Severijnen RS, Bouquet J, Madern G, Vos A, et al. Prognosis of extrahepatic biliary atresia. Arch Dis Child 1989, 64: 214-218.

- Pizani M, Rombouts K. Liver fibrosis : From the bench to clinical targets. Dig Liver Dis 2004; 36: 231-242.

- Scheuer PJ, Davies SE, Dhillon AP. Histopathological aspects of viral hepatitis.J Viral Hepat 1996:3;277-283.

- Castéra L, Vergniol J, Foucher J, Le Bail B, Chanteloup E, Haaser M, et al. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology 2005;128:343–350.

- Sang Yong Kim, Jae Yeon Seok, Seok Joo Han, and Hong Koh. Assessment of liver fibrosis cirrhosis by aspartate aminotransferase to platelet ratio in children with biliary atresia.

- Wai CT, Greenson JK, Fontana RJ, Kalbfleisch JD, Marrero JA, Conjeevaram HS, et al. A simple non-invasive index canpredict both significant fibrosis and cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology, 2003;38: 518-26.

- Arora NK, Arora S, Ahuja A, Mathur P, Maheshwari M, Das MK, et al. Alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency in children with chronic liver disease in North India. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47:1015-23.

- Dickson ER, Murtaugh PA, Wiesner RH, Grambsch PM, Fleming TR, Ludwig J,et al. Primary sclerosing cholangitis: refinement and validation of survival models. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1893-901.

- Roll J, Boyer JL, Barry D, Klatskin G. The prognostic importance of clinical and histologic features in asymptomatic and symptomatic primary biliary cirrhosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1983;308:1-7.

- Cadranel JF, Rufat P, Degos F. Practices of liver biopsy in France: results of a prospective nationwide survey. For the Group of Epidemiology of the French Association for the Study of the Liver (AFEF). Hepatology 2000;32:477–81.

- Castéra L, Nègre I, Samii K, Buffet C. Pain experienced during percutaneous liver biopsy. Hepatology. 1999;30:1529-30.

- Dienstag JL. The role of liver biopsy in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2002;36:152–60.

- Bedossa P, Darge´re D, Paradis V. Sampling variability of liver biopsy in chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology 2003;38:1449–57.

- Batts KP, Ludwig J. Chronic hepatitis an update on terminology and reporting. Am J SurgPathol1995;19:1409–17.

- Regev A, Berho M, Jeffers LJ, Milikowski C, Molina EG, Pyrsopoulos NT, et al. Sampling error and intraobserver variation in liver biopsy in patients with chronic HCV infection. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2002;97:2614.

- Siddique I, El-Naga HA, Madda JP, Memon A, Hasan F. Sampling variability on percutaneous liver biopsy in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2003;38:427-32.

- de Lédinghen V, Le Bail B, Rebouissoux L, Fournier C, Foucher J, Miette V, et al: Liver stiffness measurement in children using FibroScan: Feasibility study and comparison with Fibrotest, aspartate transaminase to platelets ratio index, and liver biopsy. J Pediatr GastroenterololNutr 2007, 45(4):443-450.

|