48uep6bbphidvals|359

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Intestinal obstruction is a common clinical occurrence and can be either dynamic or adynamic. Small bowel obstruction (SBO) is usually mechanical (dynamic) in nature, occasionally it may result from mesenteric vascular occlusion. The clinical manifestations vary according to the nature of presentation – acute or subacute, complete or partial and simple or complicated. Surgical intervention is indicated in acute intestinal obstruction due to organic pathology, closed loop obstruction, complications like strangulation or perforation. The diagnosis of strangulation is rarely possible before the gangrene has already set in. The old saying “never let the sun set or rise on an obstructed bowel” was a teaching to minimize missing strangulation. However, recent developments in radiologic modalities has promised to pick up the patients at risk of complications early and helped in decreasing delayed exploration and negative laparotomies. The primary imaging modality is plain abdominal radiography, however it has a sensitivity of 48% to 80%.[1] CT has emerged as an important diagnostic tool in the evaluation of small bowel obstruction and has a reported sensitivity of 93%, specificity of up to 100% and accuracy of 94% in diagnosing SBO.[2] Helical CT with its multiplanar reformatted imaging can accurately characterize the level, degree, cause and associated complications of obstruction. In this article we describe the multidetector CT (MDCT) findings in different causes of small bowel obstruction.

CT technique

Volume data of the abdomen is acquired with MDCT. Sagittal, coronal, and curved multiplanar reformatted images aid in the diagnosis when the axial images are indeterminate.[3] Oral administration of contrast is not required in high grade obstruction where retained fluid acts as a natural negative contrast agent.[4,5] However, in cases of partial obstruction administration of oral contrast medium (1.2% barium or 2% iodinated water-soluble contrast material) 30–120 minutes before scanning[6] is preferred for identification of enteric abnormalities in mildly distended loops.[7] CT enteroclysis (CTE) is preferred in cases of low grade partial obstruction.[8] At our institution, we perform MDCT (Philips Brilliance 40P), with a detector collimation of 2.5 mm, a section thickness Figure 1: Pseudo obstruction. (A) Coronal volumetric rendering technique(VRT) and (B) axial CECT images show dilated small and large bowel loops in a case of post operative paralytic ileus. of 3 mm, and a section reconstruction interval of 2 mm.

Approximately 100 to 120 ml of non ionic contrast material is administered at a rate of 2–3 ml/sec and images are acquired in the portal venous phase. For CT enteroclysis, the catheter (12 Fr) is placed under fluoroscopic guidance, with the catheter tip positioned in the proximal jejunum and 1.5 L saline infused at 100 ml/min. On the CT table, again 1.5 L saline is infused at 100 ml/min. 100-120 ml intravenous contrast is administered and scan performed at 50 seconds delay.

Differentiating small bowel obstruction from pseudo-obstruction

Small bowel obstruction is diagnosed on CT when there is dilatation of proximal bowel (caliber >2.5 cms) with transition to normal caliber or collapsed bowel loops distally.[9] In contrast, there is distension of both small and large bowel in ileus with colonic distension usually predominating (Figure 1A,B).[10]

The presence of intraluminal gas and particulate material in the dilated loops ‘the small bowel feces sign’ is abnormal.[12,13,15] It is associated with SBO in 82% of the patients11 and is used to identify the transition point.[12] However, it is not exclusive to obstruction and may also be seen in patients with ischemia, Crohn’s disease, infectious enteritis and vigorous jejunostomy tube feeding.[13]

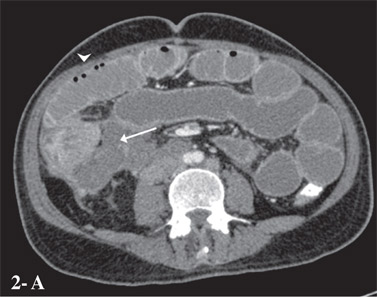

The ‘string of beads sign’ is said to be pathognomonic of small bowel obstruction (Figure 2A,B).[11]

Defining the degree of obstruction

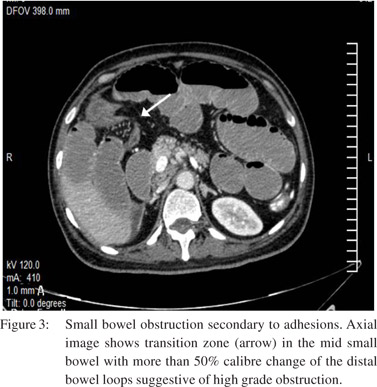

The degree of obstruction, whether it is complete, high grade partial or low grade partial[14] is more easily diagnosed on conventional contrast radiography.[11] On CT in a high-grade obstruction, there is a 50% difference in caliber between the proximal dilated bowel and the distal collapsed bowel (Figure 3).

If there is passage of the oral contrast material through the transition zone to the collapsed distal bowel it indicates incomplete obstruction – high grade if minimal contrast in the distal loops and low grade if sufficient contrast flows across the transition point.[16] On CT enteroclysis if the fold pattern in distal bowel is clearly identified it indicates low grade obstruction.[11] CTE has a reported sensitivity and specificity of 89 and 100%, respectively in the diagnosis of SBO.[8]

Defining the level of obstruction

This is determined by identifying the transition point and the relative lengths of dilated and collapsed bowel.[4] However, it is important to remember that dilated bowel loops may have an abnormal disposition. Bowel tracking in an antegrade or retrograde manner on the workstation of MDCT helps to accurately identify the transition point.[5]

Identifying complications

Closed-loop obstruction

Closed-loop obstruction (CLO) is a form of mechanical obstruction where a segment of bowel is occluded at two points along its course. It is seen in approximately 10% of SBO.[10] CT signs of CLO as described by Balthazar[17,18] include :

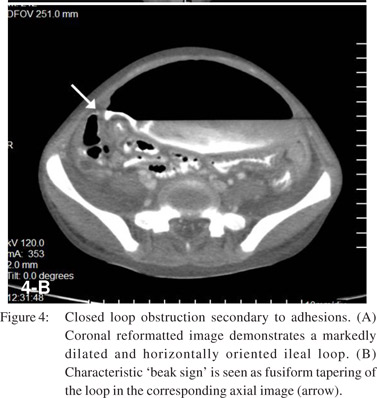

1. A distended C shaped, U shaped or ‘coffee bean’ shaped loop with engorged mesenteric vessels is seen when the loop is horizontal (Figure 4A).

2. If the bowel is more vertically oriented, fluid filled loops may be seen radiating away from the sites of obstruction.

3. Oval or triangular collapsed loops may be seen at the site of obstruction.

4. A ‘beak sign’ is seen at the site of torsion as a fusiform tapering (Figure 4B).

5. The closed loop is distended with fluid more markedly than the proximal bowel. The distal bowel is non-distended.

6. A tightly twisted mesentery ‘whirl sign’ may be seen in cases associated with volvulus.

Strangulation

Strangulation is seen in CLO or in simple obstruction associated with impaired venous drainage. It is seen in 5% to 42%19 of small bowel obstruction and is associated with a high mortality rate - from 20% to 37%.[20]CT signs of ischemia include –

1. Poor or no enhancement of the bowel wall (sensitivity 34%; specificity 100%)

2. Serrated beak sign (sensitivity 32%; specificity 100%)

3. A large volume of ascites (sensitivity 29%; specificity 98%)

4. An unusual course of the mesenteric vasculature (sensitivity 56%; specificity 95%)

5. Diffuse engorgement of the mesenteric vasculature (sensitivity 66%; specificity 95%).

Non specific findings of strangulation include thickening and increased attenuation of the affected bowel wall, a halo or “target sign,” pneumatosis intestinalis, and gas in the portal vein.[5]

A combination of the above mentioned findings should be used to diagnose strangulation.

Identifying the cause of small bowel obstruction

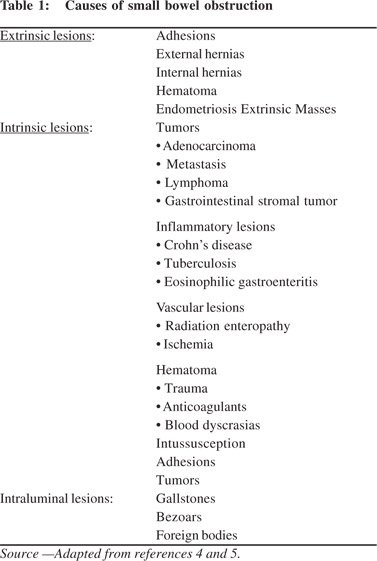

SBO can be due to extrinsic, intrinsic or intraluminal causes (Table 1). It is important to evaluate the transition point to differentiate between these. Extrinsic causes are seen adjacent to the transition point with associated extra-intestinal manifestations. Intrinsic bowel lesions are seen at the transition point as localized mural thickening. Intraluminal causes manifest as endoluminal lesions with differential density from the small bowel contents.

Extrinsic lesions

Adhesions

Adhesions are responsible for approximately 50% to 75% of cases of SBO.[20] These are commonly seen in post-operative patients (80% cases), may be associated with peritonitis (15%) or be congenital or unexplained in origin.21 SBO due to adhesions is diagnosed on CT when there is an abrupt change in the caliber of the bowel without any associated mass lesion, significant inflammation, or bowel wall thickening at the transition point (Figure 3).

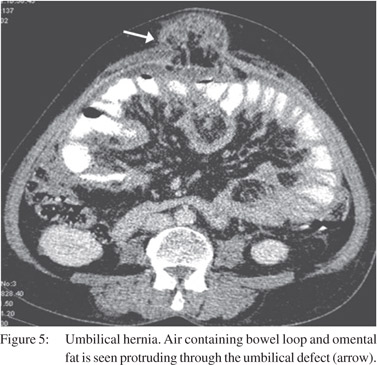

External Hernias

External hernias occur through a defect in abdominal or pelvic wall at sites of previous surgery or congenital defects.[22] Indirect inguinal hernia is the most common type and is usuallyidentified clinically.23 CT is useful for diagnosing occult hernias especially in obese patients and depicting the precise site and type of hernia, its contents and associated complications (Figure 5).

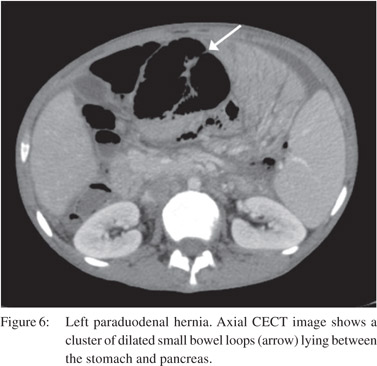

Internal Hernias

Internal hernia is a herniation of the bowel loops through developmental recesses of the peritoneum or surgically created defects in the mesentery.[21] These include right paraduodenal, left paraduodenal (Figure 6), foramen of Winslow, pericaecal, intersigmoid, transmesenteric, transmesocolic and retroanastomotic.[22] CT diagnosis is based on the identification of a cluster of small bowel loops in an abnormal position with altered course of mesenteric vessels.

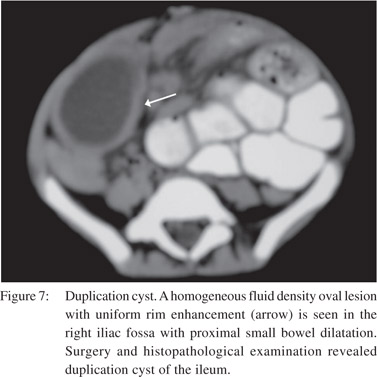

Other causes of extrinsic compression include endometriosis, hematoma, neoplastic, congenital (duplications cyst) (Figure 7) and inflammatory lesions. These may cause bowel obstruction, either by direct luminal compression or by producing a desmoplastic reaction of the bowel wall.[4]

Intrinsic Lesions

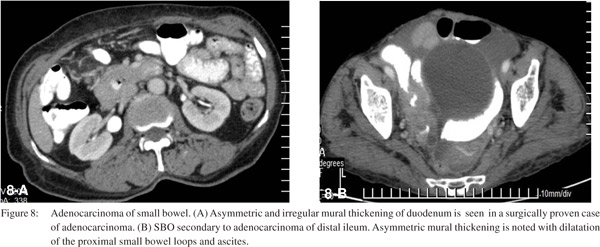

Neoplasia

Primary neoplasms of the small bowel are rare. Adenocarcinoma of small bowel is seen on CT as asymmetric, irregular mural thickening with luminal narrowing at the transition point (Figure 8). CT also helps in defining the extent of the tumor.[23]

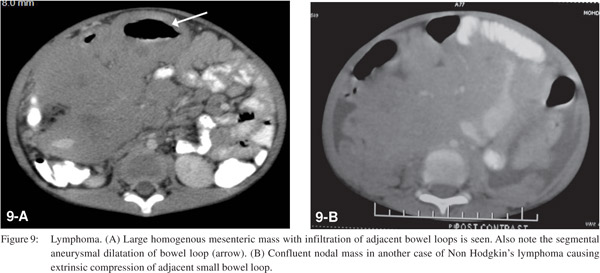

Malignancies that involve the cecum and proximal colon can also result in SBO when there is involvement of the ileocecal valve. Nodal non-Hodgkin lymphomas may arise in the mesentery and grow to invade small bowel segments and may cause obstruction by compression, kinking, and infiltration.[24] On CT homogenous mesenteric nodal mass with infiltration of adjacent bowel loops is seen (Figure 9). Primary non-Hodgkin lymphomas of the small bowel are non-obstructing soft lesions that infiltrate the bowel wall and tend to produce early cavitation. Peritoneal carcinomatosis can lead to SBO by either extrinsic compression or desmoplastic reaction with resultant bowel loop angulation and distortion.[25] The common causes include carcinoma of the ovary, colon, stomach, pancreas, breast, and endometrium.

Crohn’s Disease

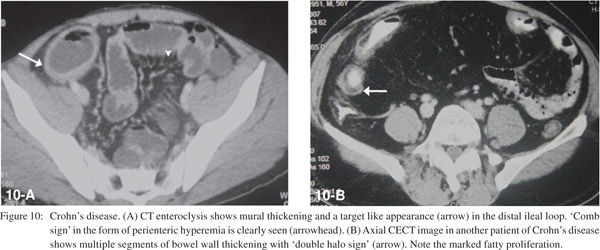

SBO can occur in the active phase due to acute inflammation causing luminal narrowing. Small bowel loops show mural stratification with target appearance and peri-enteric hyperaemia resulting in the ‘comb sign’ (Figure 10A). In the chronic phase, cicatricial stenosis of the bowel segments with fibrofatty proliferation is seen (Figure 10B).10 CT also helps to diagnose complications like abscesses, fistulas, post-operative adhesions, incisional hernias and malignancy.[11]

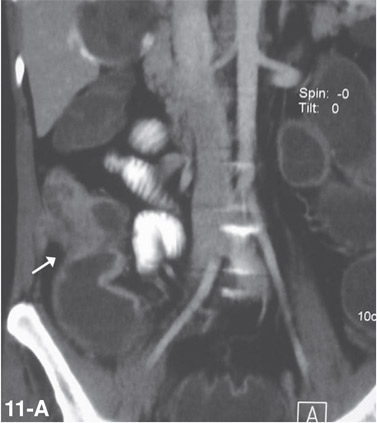

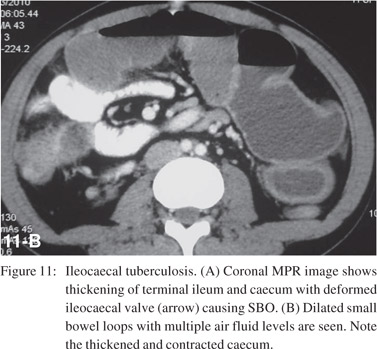

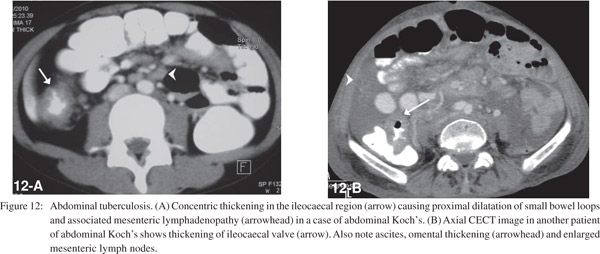

Tuberculosis

Small bowel tuberculosis can be ulcerative or hypertrophic and commonly involves the ileocaecal region. CT demonstrates asymmetric, irregular wall thickening of terminal ileum and caecum (Figure 11) with enlargement of ileocaecal valve and mesenteric adenopathy (Figure 12) with central low attenuation areas suggestive of necrosis.[26]

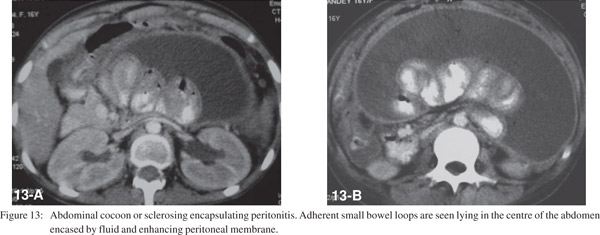

Abdominal Cocoon

Also known as sclerosing encapsulating peritonitis, it is a rare condition where the small bowel is encased by a thick fibrotic peritoneum.[27] The common etiological factors include tuberculosis, prior abdominal surgery or peritonitis and chronic peritoneal dialysis. CT shows concentration of a part of or the entire small bowel in the center of the abdomen encased by a soft tissue-density mantle (Figure 13).[28]

Radiation Enteritis

Commonly occurs after 1 year of therapy in the irradiated area usually the pelvis. SBO occurs primarily due to adhesive and fibrotic changes in the mesentery and occasionally due to radiation serositis which causes luminal narrowing and dysmotility.[29] CT shows mural thickening, angulation and kinking of the bowel wall and retraction of the mesentery.[23]

Hematoma

Can occur due to trauma, anticoagulant medication or blood dyscrasias and cause SBO due to luminal narrowing. Noncontrast CT shows hyperattenuating circumferential mural thickening.[23,30]

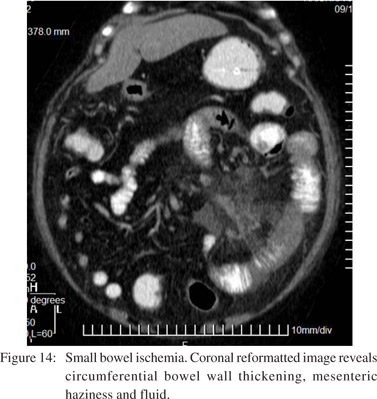

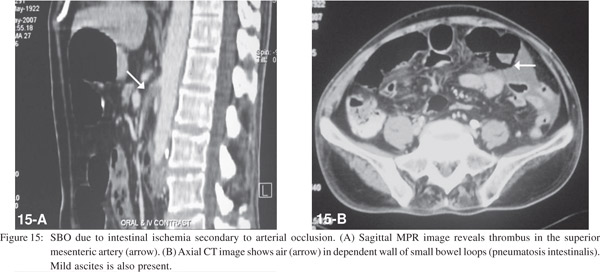

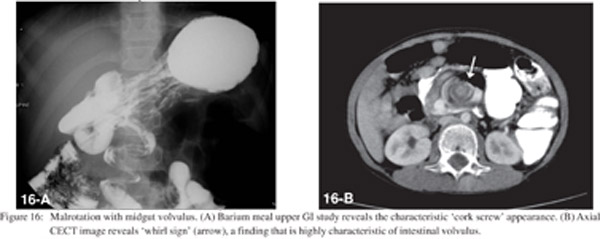

Vascular

Bowel ischemia occurs due to occlusion of the mesenteric arterial or venous vascular supply. CT shows thrombosis or occlusion of the mesenteric vessels, thickening of the bowel wall with asymmetric wall enhancement, pneumatosis and air in the portal venous system (Figures 14 and 15).[20] Bowel ischemia may result secondary to volvulus, commonly seen in association with malrotation. This is characterized by “cork screw appearance” on upper GI study (Figure 16A) and the “whirl sign” on CECT (Figure 16B).

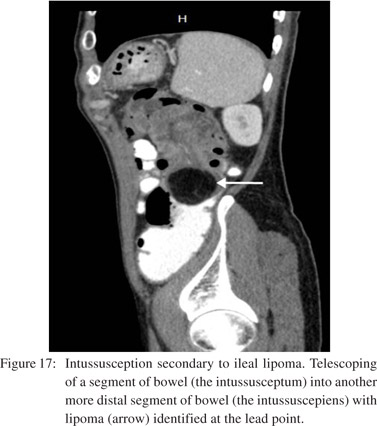

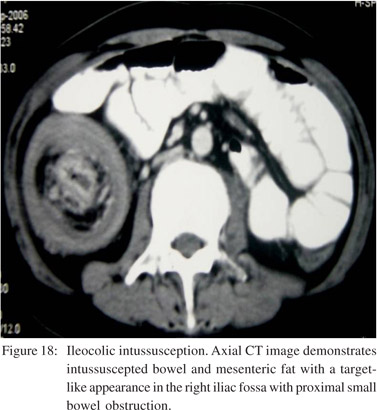

Intussusception

Small bowel intussusception may result from various extrinsic, intrinsic, or intraluminal processes.[31] 80% of cases in adults are associated with underlying causes such as neoplasm (Figure 17), adhesion, inverted Meckel’s diverticulum, foreign body, prior history of abdominal surgery and bowel dysmotility disorders.[20,21,24,32] There is invagination of a proximal small bowel loop and part of its mesentery (intussusceptum) into the lumen of the distal small bowel or colon (intussuscepiens).[21] In early stages a dilated bowel loop containing an eccentric crescent of fat is seen on CT. In advanced disease a sausage shaped mass with alternating areas of low and high attenuation and features of SBO are seen (Figure 18). Delayed diagnosis results in a reniform mass with findings of ischemia and necrosis.[10]

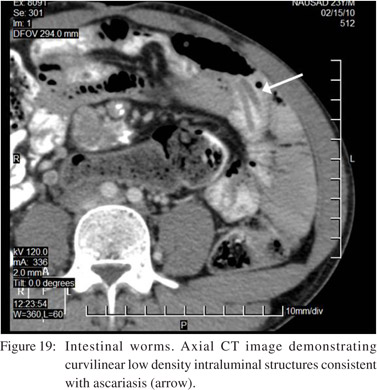

Intraluminal causes

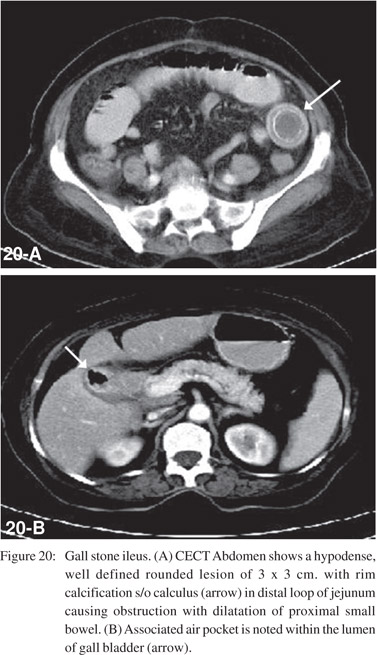

These include gallstones, foreign bodies, bezoars, worms (Figure 19) or meconium. Gallstone ileus usually occurs in elderly women. CT demonstrates the triad of ectopic gallstone, gas in the shrunken gallbladder or biliary tree, and mechanical bowel obstruction (Figure 20).[33]

Bowel obstruction caused by a foreign body usually occurs in children or mentally disturbed or disabled patients.[21] Bezoars are impacted luminal masses containing indigestible food and are usually seen in post gastrectomy patients. At CT, a bezoar is seen as an intraluminal mass with an ovoid shape and a mottled gas pattern.[34]

Conclusion

Small bowel obstruction is evaluated clinically on the basis of history, examination and laboratory results with conventional radiograph being the radiological investigation of first choice. CT is highly sensitive and specific in determining the presence of bowel obstruction. MDCT with its multiplanar reformatted images can accurately diagnose the level, severity and cause of obstruction. Complications like CLO and strangulation, which have important implications on patient management can also, be identified. CT should be considered in the evaluation

of SBO, especially where the plain film findings are equivocal and complications are suspected.

References

1. Frager D, Medwid S, Baer J, Mollinelli B, Freidman M. CT of small bowel obstruction. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162:37–41.

2. Suri S, Gupta S, Sudhakar PJ, Venkataramu NK, Sood B, Wig JD. Comparative evaluation of plain films, ultrasound and CT in the diagnosis of intestinal obstruction. Acta Radiol. 1999;40:422–8.

3. Caoili EM, Paulson EK. CT of small-bowel obstruction: another perspective using multiplanar reformations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:993–8.

4. Furukawa A, Yamasaki M, Furuichi K, Yokoyama K, Nagata T, Takahashi M, et al. Helical CT in the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. Radiographics. 2001;21:341–55.

5. Silva AC, Pimenta M, Guimaraes LS. Small bowel obstruction: What to look for. Radiographics. 2009;29:423–39.

6. Frager DH, Baer JW. Role of CT in evaluating patients with small-bowel obstruction. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1995;16:127–40.

7. Maglinte DDT, Balthazar EJ, Kelvin FM, Megibow AJ. The role of radiology in the diagnosis of small bowel obstruction. Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168:1171–80.

8. Magnelite DDT, Sandrasegaran K, Lappas JC, Chiorean M. CT Enteroclysis. Radiology. 2007;245:661–71.

9. Fukuya T, Hawes DR, Lu CC, Chang PJ, Barloon TJ. CT diagnosis of small-bowel obstruction: efficacy in 60 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;158:765–9.

10. Sandrasegaran K, Maglinte DDT, Howard TJ, Kelvin FM, Lappas JC. The multifaceted role of radiology in small bowel obstruction. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2003;29:319–35.

11. Burkill GJC, Bell JRG, Healy JC. The utility of computed tomography in acute small bowel obstruction. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:350–9.

12. Jacobs SL, Rozenblit A, Ricci Z, Roberts J, Milikow D, Chernyak V, et al. Small bowel faeces sign in patients without small bowel obstruction. Clin Radiol. 2007;62:353–7.

13. Mayo-Smith WW, Wittenberg J, Bennett GL, Gervais DA, Gazelle GS, Mueller PR. The CT small bowel faeces sign: description and clinical significance. Clin Radiol. 1995;50:765–7.

14. Shrake PD, Rex DK, Lappas JC, Maglinte DD. Radiographic evaluation of suspected small bowel obstruction. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:175–8.

15. Singh J, Kumar R, Kalyanpur A. “Small bowel feces sign”: a CT sign in small bowel obstruction. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2006;16:71–4.

16. Maglinte DD, Gage SN, Harmon BH, Kelvin FM, Hage JP, Chua GT, et al. Obstruction of the small intestine: accuracy and role of CT in diagnosis. Radiology. 1993;188:61–4.

17. Balthazar EJ, Bauman JS, Megibow AJ. CT diagnosis of closed loop obstruction. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1985;9:953–5.

18. Balthazar EJ, Birnbaum BA, Megibow AJ, Gordon RB, Whelan CA, Hulnick DH. Closed-loop and strangulating intestinal obstruction: CT signs. Radiology. 1992;185:769–75.

19. Sarr MG, Bulkley GB, Zuidema GD. Preoperative recognition of intestinal strangulation obstruction: prospective evaluation of diagnostic capability. Am J Surg. 1983;145:176–82.

20. Bizer L, Liebling R, Delany H, Gliedman ML. Small bowel obstruction: the role of nonoperative treatment in simple intestinal obstruction and predictive criteria for strangulation obstruction. Surgery. 1981;89:407–13.

21. Herlinger H, Rubesin SE, Morris JB. Small bowel obstruction. In: Gore RM, Levine MS, editors. Textbook of gastrointestinal radiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2000.p.815–37.

22. Ghahremani GG. Abdominal and pelvic hernias. In: Gore RM, Levine MS, editors. Textbook of gastrointestinal radiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2000.p.1993–2009.

23. Boudiaf M, Soyer P, Terem C, Pelage JP, Maissiat E, Rymer R. CT evaluation of small bowel obstruction. Radiographics. 2001;21:613–24.

24. Herlinger H, Maglinte DDT. Small bowel obstruction. In: Herlinger H, Maglinte DDT, editors. Clinical radiology of the small bowel. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1989.p.479–509.

25. Torreggiani WC, Harris AC, Lyburn ID, Al Nakshabandi NA, wirewich CV, Brenner C, et al. Computed tomography of small bowel obstruction: Pictorial essay. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2003;54:93–9.

26. Hulnick DH, Megibow AJ, Naidich DP, Hilton S, Cho KC, althazar EJ. Abdominal tuberculosis: CT evaluation. Radiology. 1985;157:199–204.

27. Rajul Rastogi. Abdominal Cocoon secondary to Tuberculosis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:139–41.

28. Wig JD, Gupta SK. Computed tomography in abdominal cocoon. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:259–60.

29. Horton KM, Fishman EK. The current status of multidetector row CT and three-dimensional imaging of the small bowel. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:199–212.

30. Frager DH, Baer JW, Rothpearl A, Bossart PA. Distinction between postoperative ileus and mechanical small-bowel obstruction: value of CT compared with clinical and other radiographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1995;164:891–4.

31. Abiri S, Baer J, Abiri M. Computed tomography and sonography in small bowel intussusception: a case report. Am J Gastroenterol. 1986;81:1076–7.

32. Agha FP. Review: intussusception in adults. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:527–31.

33. Rigler LG, Bormen CN, Noble JF. Gallstone obstruction: pathogenesis and roentgen manifestations. JAMA. 1941;77:1753–9.

34. Quiroga S, Alvares-Castells A, Sebastia MC, Pallisa E, Barluenga E. Small bowel obstruction secondary to bezoar: CT diagnosis. Abdom Imaging. 1997;22:315–7.