|

Sowndarya Madugula1, Prabu D1, Sindhu R1, Dinesh Dhamodhar1, Rajmohan M1, Bharathwaj V V1, Sathiyapriya S1, Premkumar Devdoss2, Yuvaraj Jayaraman3 1Public health dentistry, SRM Dental college, Chennai. 2Department of Medical Oncology, Govt. Arignar Anna Memorial Cancer hospital, Kanchipuram. 3Scientist G at National Institute of Epidemiology, Ayapakkam, Chennai.

Corresponding Author:

Prof. Prabu D Email: researchphdsrm@gmail.com

Abstract

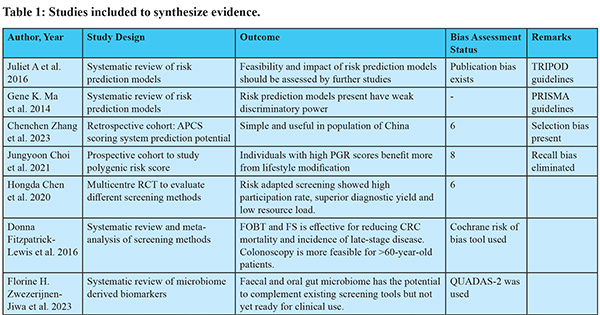

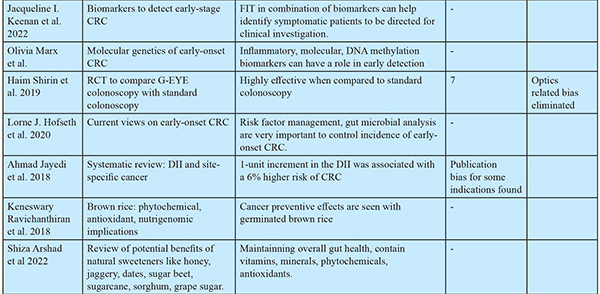

Background: Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed and second most deadly cancer in 2020. Although the incidence of disease has decreased among older adults, recently there has been an alarming emergence of early-onset colorectal cancer among people <50 years of age. 9.4% of cancer-related deaths globally occured due to colorectal cancer in 2022. The critical shift in health-care focus from treatment to disease prevention necessitates the development of a well-thought-out integrative prevention strategy that is both practical and evidence-based. The study's goal is to provide a holistic, wellness-oriented disease prevention strategy to reduce the incidence of both early-onset and late-onset colorectal cancer. Materials and Methods: A systematic search from databases (PubMed, Wiley, Elsevier, and Google Scholar) for articles published in the past 7 years in peer-reviewed journals was conducted, aiming at articles regarding risk factors and modification, screening and early detection with biomarkers, diet and lifestyle, traditional and modern chemo-preventive compounds, immunoprevention, and oral dysbiosis. All of the authors independently assessed the quality of the studies. Results: 32 studies, including 13 systematic reviews, 3 cohorts, 3 randomized control trials, 1 case-control, 3 in vitro, 2 in vivo, and 7 reviews. Evidence synthesis is presented as an integrated preventive strategy for colorectal cancer, focusing on different aspects of prevention. Conclusion: A holistic approach to CRC prevention should include improved screening, early detection, dietary and lifestyle changes, good communication to perceive risk, need-based nutrition supplementation, and stress management.

|

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is an uncontrollable growth occurring in the colon and rectum1 that starts in the innermost mucosal layer, grows outward (polyp), and spreads through lymphatics. The polyps, which are sessile, serrated, traditional serrated polyps, polyps with a diameter greater than 1 cm and more than 3 in number, and polyps with a dysplastic nature have the highest risk for CRC. Adenocarcinoma, the most common type of CRC, arises from glandular epithelial cells. Other less common types are carcinoid tumors from hormone-making cells, gastro-intestinal stromal tumors from intestinal cells of Cajal, lymphomas from the immune cells of the digestive tract, and sarcomas that start in blood vessels and connective tissues of the walls of the colon and rectum2. Among CRCs, colon cancer is predominant (59.5% of new cases and 61.9% of deaths)3. Incident cases (45.94%) and deaths (49%) are more remarkable in areas with higher income levels4. Despite various methods of CRC prevention openly available in scientific literature and the availability of recommendations given by international organizations, the emerging incidence of early-onset CRC cases is posing a public health challenge, as the global incidence of CRC cases is predicted to reach 3.2 million in 20405. This disparity results from various barriers to CRC prevention, among which the most important is a lack of awareness among the general population and a lack of perception towards the importance of prevention among health care providers. To address this gap, the present review focuses on creating awareness by providing a holistic insight into the prevention of CRC.

Methodology

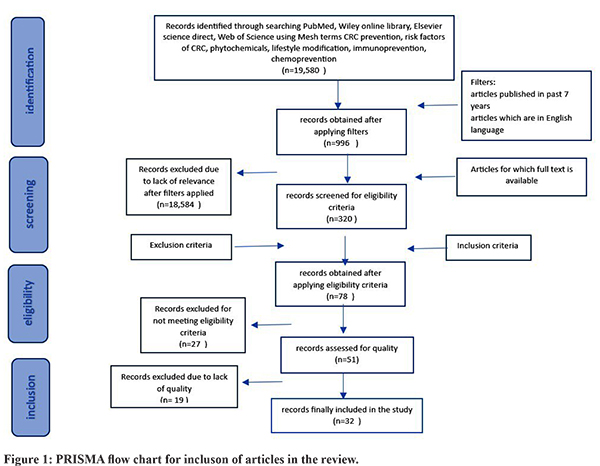

Search Strategy: We systematically searched PubMed, Web of Science, Elsevier, Wiley Online Library, and Google Scholar databases for articles using keywords and included studies following PRISMA guidelines (Figure 1).

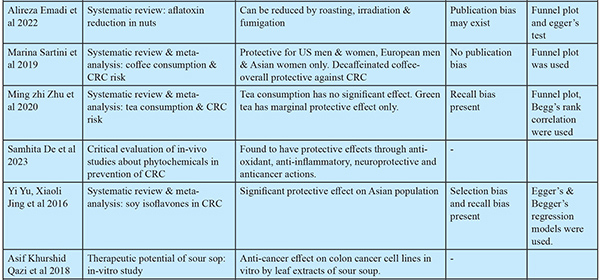

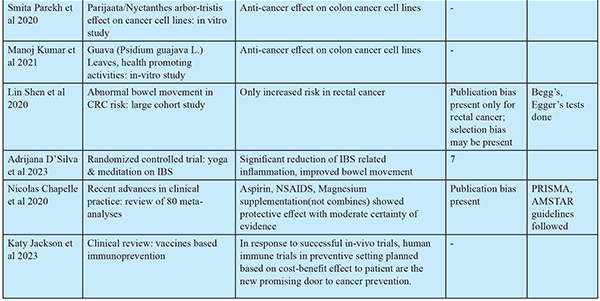

Study Selection: Inclusion and exclusion criteria: Articles published in peer-reviewed journals in the past 7 years were included. Criteria for inclusion included (i) articles that contained preventive methods for colorectal cancer; (ii) studies that were published in the past 7 years to include recent evidence; and (iii) articles that were available in full text. Criteria for exclusion included (i) studies conducted on cancers other than CRC. (ii) studies conducted on patients already diagnosed with cancer. (iii) studies available in languages other than English. Quality assessment: The quality of the studies was methodologically examined for adequate sample size, selection bias, and standardization of reporting guidelines. Bias was assessed for observational studies done using the New Castle Ottawa scale and for RCTs using the Jadard scoring system. Scores for relevant studies indicated low risk of bias (scores 6 to 8). The studies selected were reviewed by rest of the investigators for eligibility and quality assessment. The extraction of data pertaining to authors, study design, and outcomes was done and synthesized in the form of narrative synthesis, which was later clustered and presented in tabular forms. (Table 1). The extraction of findings from the studies was focused on (i) screening, (ii) early detection, (iii) dietary modification, (iv) lifestyle modification, (v) risk factor management, (v)chemoprevention, and (vi) immunoprevention.

Results

(Figure 1)

Identifying The Risk6,7

Some currently available risk prediction models include APCS (Asia Pacific Colorectal Cancer Screening score) questionnaires8 and PRA (Polygenic Risk Assessment) genetic tests9. Risk prediction can increase screening uptake, encourage knowledge and lifestyle changes due to an increase in risk perception, and reduce the burden of screening. However, there are challenges such as population variability preventing the development of "one for all model," communication of risk output individually to large populations, and differences in location, socio-economic, cultural, and resource availability of the population. Addressing these challenges is crucial for effective cancer prevention and management.

Early Detection by Biomarkers [Table 2-4] Non-invasive biomarkers provide convenient screening, aid in increasing screening uptake, and reduce the probability of over screening by invasive methods like colonoscopy.

Biomarkers for CRC:14,15

Oral Dysbiosis In CRC:16,17,18

Different studies identified various bacteria associated with CRC, including Fusobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Prevotella, Veillonella, and Treponema denticola, present in individuals with poor oral health. They may play a crucial role in the development, progression, and potential diagnosis of CRC. In PPI (Proton Pump Inhibitor) users, patients with achlorhydria, IBD (Inflammatory Bowel Disease), and the gastric acidic barrier get weakened, leading to the survival of harmful oral-ingested bacteria. They colonize the intestinal tract and may contribute to tumorigenesis by (i) activating inflammatory and NF-?B cascade pathways and (ii) creating an immunosuppressive microenvironment. Fusobacteium nucleatum is most significantly associated with CRC. Actinomyces odontolyticus increased only at an early stage of CRC, while Parvimonas micra, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Solobacterium moorei, Gemella morbillorum, and Fusobacterium nucleatum increased at both early and late stages [Table 4]. Some of the new diagnostic techniques for identifying oral dysbiosis include PCR, RT-PCR (Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerized Chain Reaction), metagenomics, gel-based electrophoresis, etc.

Early-Onset CRC:19,20

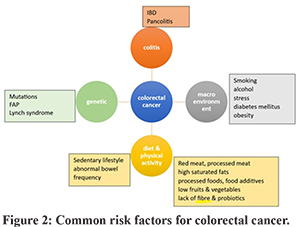

Early-onset CRC differs from late-onset CRC in age of incidence (<50 years old), location of common occurrence (left distal colon and rectum in 55-80% of people), and frequency of oncogenic mutations. It is poorly differentiated histologically, with a distinct DNA methylation profile. Its polygenic risk score is higher and has worse survival. Risk factors for early-onset CRC:19 (Figure 2) Family history and hereditary occurrence are 30% common with familial adenomatosis polyposis (FAP), Lynch syndrome (5%), and other mutations (12-16%). Diabetes can increase the risk of cancer in the colon (38%) and rectum (20%). Chronic inflammatory conditions like IBD (pancolitis) in the 4th decade (30%), and celiac disease are common risk factors. Diet, alcohol, smoking, lack of physical activity, obesity in childhood, and calorie restriction in children are other risk factors. Dietary aspects like high intake of processed and red meat (22%), cooking methods like deep frying which releases glycation end products that are pro-carcinogenic, and usage of food additives like nitrates in processed meat, over-use of synthetic dyes, monosodium glutamate, titanium dioxide (E171) (a food whitening agent) (>1% of food weight), and high fructose corn syrup increase the risk of EOCRC. Maternal stress during pregnancy and childhood perceived stress are also important risk factors. Gut dysbiosis due to increased numbers of Fusobacterium nucleatum, Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, and Salmonella enterica causes intestinal dysbiosis, inflammation, evasion of the tumoral immune response, and activation of pro-tumoral signalling. Repeated short-term or long-term exposure to antibiotics also alters the gut microbiota, which increases the risk of EOCRC.

Management of Modifiable Risk Factors:20,21,22

Diet Modification Recommendations to Prevent CRC:6,7,9,28,29,30,31: Table 6 highlights the dietary recommendations for prevention of CRC.

Natural Compounds:43,44

Natural compounds that are found to have protective effects through anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, neuroprotective and anticancer actions include: 1. Curcumin (polyphenol) (turmeric) 2. Resveratrol (stilbenes) (red grapes) 3. EGCG (epigallocatechin) (green tea) 4. Fisetin (hydroxy flavone) (strawberries, apples, onions, and cucumbers) 5. Genistein (isoflavone) in combination with chemotherapeutic agents (ginseng root) 6. Apple polysaccharides (apples) 7. Mushroom glucans (edible mushrooms) 8. Paris saponin 7 (ginseng plant) 9. Soy saponins (soy beans) 10. Soy isoflavones were shown to have significant protective effect in Asian population.45 11. Leaf decoctions: A.muricata / Graviola / Soursop: The leaf extracts of Graviola contains phytochemicals Annomuricin A, B, C, E & Muricapentocin which is found to have anticancer effects on colon cancer cell-lines in vitro.46 Parijaata/Nyctanthes arbor-tristis for antioxidant & antibacterial properties47, guava/Psidium guajava L for antioxidant, antimicrobial actions48 showed anti-cancer effects on cancer cell lines. 12. Terminalia chebula Retz/Hartaki/Kadukkai/Manahei is mild laxative, anti-inflammatory, remedy for hemorrhoids. Hydroalcoholic extracts from this was found to have significant cytotoxicity against HCT-116 colon cancer cells indicating promising anti-cancer activity.49

Bowel Movement

Abnormal frequency of bowel movements is not associated with colon cancer, but it suggests an increased risk for rectal cancer.50

Physical Activity51

At least 30 minutes of physical activity is necessary to maintain health of gastrointestinal tract.

Chemoprevention55

A low certainty of evidence supports a significant effect against CRC incidence with long-term intake of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) in low dose. Moderate certainty of evidence supports that aspirin in low doses has protective action as a chemo preventive agent. Magnesium had a significant protective effect when at least 225 mg/day was consumed, supported by low certainty of evidence. Very low certainty of evidence exists to prove the protective effect of vitamin D alone or in combination with calcium. The evidence for Folic Acid, Vitamins E, C, Multivitamins, Beta Carotene, and Selenium as protective agents is very weak. An analysis of micronutrient levels is essential before prescribing the micronutrient supplement.

Immunoprevention56

Immunoprevention is the concept of preventing cancer development using agents that enhance the immune system to survey and destroy tumor cells. The development of tumors is fostered by evading immune cells and creating an immune-suppressive environment for the immune response. Vaccines may help overcome this immunosuppressive environment conducive to cancer growth. The development of such vaccines will be based on tumor-associated antigens and tumor-specific antigens. Multivalent vaccines, complemented with immune adjuvants, help eliminate a larger number of tumor cells. So far, human trials of CRC vaccines have failed due to the administration of vaccines during advanced stages of carcinogenesis because of patients’ inability to mount an effective immune response. But in vivo clinical trials in mouse models well before tumor incidence (presence of genetic risk, polyps) reduced the cancer risk by 100%. Also, the vaccinated mice with genetic susceptibility gave birth to offspring who were free of polyps (antibody transferred through breast feeding). Human trials in a preventive setting need to be conducted to accurately assess the efficacy of CRC vaccines. Recently, the first randomized controlled trial tested the MUC1 vaccine against CRC in a prevention setting, and results are awaited.

Discussion

The present review, including 32 studies, provides insights on holistic preventive strategies for colorectal cancer. Risk identification among the general population involves developing prediction models relevant to a specific population, followed by risk stratification into high, medium, and low-risk populations6,7 based on which specific screening strategy10 would be employed, as in the low-risk population, FIT, non-invasive biomarkers, in the high-risk population, invasive biomarkers, FOBT, FS11, and then colonoscopy10 for diagnostic conformation. Among early detection biomarkers, stool-based ones14 are non-invasive and effective. In cases of early-onset CRC, fecal calprotectin, the Cologuard test, the EpiproColon test, and miRNA biomarkers were found to be effective. The recommendation of a healthy diet replacing unhealthy diet components is given elaborately in the present review. Including complex carbohydrates23 like red, black, and brown rice, positive millets24, plant-based unpolished whole proteins, and sprouted grains can increase fiber intake and provide good glycemic control. For meat intake, avoiding red (beef, pork, lamb, liver, meatballs) and processed (bacon, hot dog, sausage, etc.) meats35, including white meats like chicken, turkey, duck, rabbit, and fish prepared by boiling, steaming, pressure-cooking, and stir-frying methods36 once a week, while deep-frying, barbecued, smoked, and pickled meats should be avoided. For cooking, hydrogenated vegetable oils can be replaced by natural, unfiltered sesame oil and olive oils. Low-fat dairy products like A2 pasteurized milk27, yogurt, natural dairy cheese, and buttermilk30 are found to be protective. Intake of fresh fruits like apples, papaya, citrus fruits, pomegranates, amla, berries, watermelon, and kiwi39 should be regular and frequent. Increased intake of non-starchy, native, and water-rich vegetables, including cruciferous vegetables40, has been found to be protective. Regular intake of vegetable juices38 is recommended for people with healthy GIT. Other dietary factors found to be protective include good-quality seeds like pumpkin, sunflower, hemp, chia, sesame, and flax seeds (avoid in cases of allergy), natural probiotic foods like yogurt, fermented rice, and sauerkraut, a cup per day of decaffeinated coffee41, and rolled or steel-cut oats with fresh fruits26. The review recommends avoiding intake of alcohol, tobacco, soft drinks, canned food, processed and packaged food items, food additives and preservatives, fast foods, nuts like peanuts, which are highly prone to aflatoxin37 presence, and wheat and wheat products in cases of gluten sensitivity. At least 30 minutes of physical activity at least three times per week51, yoga poses like Parighasana, Ardha matsyendrasana, Salamba setu bandhasana, Ananda balasana (help with IBS), Uttanasana, Utthita Parsvakonasana, Ushtrasana, Dhanurasana, Eka Pada Rajakapotasana, Apanasana, Savasana (help with digestion and colon health), and methods of prasnayam53 like nadisuddhi and kapalbhati have also been found to be helpful for GI health. For chemoprevention55, moderate evidence supports low-dose aspirin, and low evidence supports magnesium 225 mg/day as chemopreventive agents for patients with high-risk serrated or adenomatous polyps. New evidence also suggests precise supplementation to address the deficiency of micronutrients. The protective role of natural compounds43, like curcumin, resveratrol, genistein, soursop, etc., is yet to be established in large-scale trials before being recommended as preventive agents. The most recent research on developing immuno-preventive agents56 is going on in a promising manner. Recently, a randomized controlled trial on the MUC1 vaccine against CRC in a prevention setting was conducted, and the results are yet to be unfolded. Similar evidence was presented in an umbrella review by Sajesh K. Veettil57, where an association was found between lower CRC risk and higher intakes of dietary fiber, dietary calcium, and yogurt and lower intakes of alcohol and red meat. In another umbrella review by Jakub ´Switalski et al., FIT was found to be effective and economical to be used in large-scale population screening of CRC58. Quercetin available in onions, elagic acid in green tea, and apples were found to be effective in preventing the recurrence of polyps59. The strength of the study lies in exploring prevention strategies in a holistic manner relevant to present-day scenarios applicable to the general population and providing education regarding this at a level understandable to the general population from all streams. The limitation of the study is the smaller number of studies included in multiple aspects of prevention. Elaborate studies, considering a greater number of studies in each aspect of prevention, are needed to be conducted to develop policy recommendations for CRC prevention. Future research may focus on developing risk prediction models relevant to respective populations, developing diet and lifestyle modification methods with measurable outcomes, and testing the performance of cost-effective bio-markers for risk identification in resource limited settings. In conclusion, the study suggested an integrated holistic approach for risk identification and stratification, improving screening uptake with non-invasive biomarkers, to motivate people to take steps towards prevention. Effective interventions for diet and lifestyle modification, supplementation on a deficiency basis, proper use of phytochemicals for risk factor modification, along with correction of oral dysbiosis60, and chemoprevention in high-risk populations, constitute a holistic approach for risk reduction and early intervention to prevent the progression to colorectal carcinoma.

References - Division of Cancer Prevention and Control, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/colorectal/index.htm 2020 [accessed on 20th Dec 2022]

- Colorectal cancer, American cancer society, https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/colon-rectal-cancer.html 2020 [accessed on 20th Dec 2022]

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel R.L, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. Ca Cancer J Clin 2021;71:209-249.

- Colorectal cancer, World Bank group, https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/10.1596/978-1-4648-0349-9_ch6 ; 2015 [accessed on 20th Dec 2022]

- Yue Xi, Pengfei Xu. Global colorectal cancer burden in 2020 and projections to 2040. Translational Oncology 2021; 14:101174.

- Usher-Smith J.A, Walter F.M,Emery J.D, Win A.K,Griffin S.J. Risk Prediction Models for Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancer Prev Res 2016; 9:13-26

- Ma G.K and Ladabaum U. Personalizing Colorectal Cancer Screening: A Systematic Review of Models to Predict Risk of Colorectal Neoplasia; Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014; 12:1624-1634.

- Zhang C, Zhang L, Zhang W, Guan B, Li S. An adjusted Asia-Pacific colorectal screening score system to predict advanced colorectal neoplasia in asymptomatic Chinese patients; BMC Gastroenterol. 2023; 23:223.

- Choi J, Jia G, Wen W, Shu X, Zheng W. Healthy lifestyles, genetic modifiers, and colorectal cancer risk:a prospective cohort study in the UK Biobank. Am J Clin Nutr 2021;113:810–820.

- Chen H, Lu M, Liu C, Zou S, Du L, Liao X, et al. Comparative Evaluation of Participation and Diagnostic Yield of Colonoscopy vs Fecal Immunochemical Test vs Risk-Adapted Screening in Colorectal Cancer Screening: Interim Analysis of a Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial (TARGET-C). Am J Gastroenterol 2020;115:1264–1274.

- Fitzpatrick-Lewis D,Ali M.U, Warren R,Kenny M,Sherifali D, Raina P. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2016; 15:298-313.

- Zwezerijnen-Jiwa F.H, Sivov H, Paizs P, Zafeiropoulou K, Kinross J. A systematic review of microbiome-derived biomarkers for early colorectal cancer detection. Neoplasia 2023; 36:1-10.

- Shirin H, Shpak B, Epshtein J, Karstensen J.D, Hoffman A, Ridder R, et al. G-EYE colonoscopy is superior to standard colonoscopy for increasing adenoma detection rate: an international randomized controlled trial (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2019;89:545-553.

- Keenan J.I, Frizelle F.A, et al. Biomarkers to Detect Early-Stage Colorectal Cancer. Biomedicines 2022;10:255.

- Marx O, Mankarious M, Yochum G. Molecular genetics of early-onset colorectal cancer. World J Biol Chem 2023; 14:13-27.

- Reitano E, de’Angelis N, Gavriilidis P, Gaiani F, Memeo R, Inchingolo R, et al. Oral Bacterial Microbiota in Digestive Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2021; 9: 2585.

- Negrut R.L, Cote A, Maghiar A.M. Exploring the Potential of Oral Microbiome Biomarkers for Colorectal Cancer Diagnosis and Prognosis: A Systematic Review. Microorganisms 2023; 11: 1586.

- Al-Terehi M, Shershab S, Al-Rrubaei H.A, Al-Saadi A.H. Some Oral Pathogenic Bacteria, Isolation and Diagnosis. J Pure Appl Microbiol 2018; 12: 1495-1498.

- Hofseth L.J,Hebert J.R, Chanda A, Chen H, Love B.L, Pena M.M, et al. Early-onset colorectal cancer: initial clues and current views. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 17:352–364.

- Jayedi A, Emadi A. Dietary Inflammatory Index and Site-Specific Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis. Adv Nutr 2018;9:388–40.

- Hossain Md.S, Karuniawati H, Jairoun A.A, Urbi Z,Oo D.J, John A, et al. Colorectal Cancer: A Review of Carcinogenesis, Global Epidemiology, Current Challenges, Risk Factors, Preventive and Treatment Strategies. Cancers 2022; 14:1732.

- Sivsri Roshan G.M, Sindhu R, Dinesh D, Prabu D, Rajmohan M, Bharathwaj V V. Cognizance about potential cancer risks due to cone-beam computed tomography systems among dental professionals. Int J Health Sci 2022; 6:6574-6583.

- Ravichanthiran K, Ma Z.M, Zhang H,Cao Y, Wang C.W, Muhammad S, et al. Phytochemical Profile of Brown Rice and Its Nutrigenomic Implications. Antioxidants 2018; 7:71.

- Chen Y, Zhang R, Xu J, Ren Q. Alteration of intestinal microflora by the intake of millet porridge improves gastrointestinal motility. Front Nutr 2022; 9:965687.

- kalra N, Mukerjee A, Sinha S, Muralidhar V, Serin Y, Tiwari A, et al. Current updates on the association between celiac disease and cancer, and the effects of the gluten-free diet for modifying the risk (Review). Int J Funct Nutr 2022; 3:2.

- Oatmeal with fresh fruit, cancer prevention, American Institute for Cancer Research, https://www.aicr.org/cancer-prevention/recipes/oatmeal-with-fresh-fruit/ 2023 [accessed on 1/July 2023]

- Arshad S, Rehman T, Saif S, Rajoka Md.S.R, Ranjha Md.M.A, Hassoun A, et al. Replacement of refined sugar by natural sweeteners: focus on potential health benefits. Heliyon 2022; 8: e10711.

- Barrubés L, Babio N, Becerra-Tomás N, Rosique-Esteban N, Salas-Salvadó J. Association Between Dairy Product Consumption and Colorectal Cancer Risk in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Epidemiologic Studies. Adv Nutr 2019;10:S190–S21.

- Mori S,Fujiwara-Tani R, Kishi S, Sasaki T, Ohmori H, Goto K, et al. Enhancement of Anti-Tumoral Immunity by ß-Casomorphin-7 Inhibits Cancer Development and Metastasis of Colorectal Cancer. Int. J.Mol. Sci. 2021; 22: 8232.

- Liang Z, Song X, Hu J, Wu R, Pengda, Dong Z et al. Fermented Dairy Food Intake and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2022; 12:812679.

- Madhavan A, Sankar P, Ravindranath K.J, Soundhararajan R, Srinivasan H. Screening the Efficacy of Compounds from Ghee to Control Cancer: An In silico Approach. Biointerface Res Appl Chem 2021; 11:14115 – 14126.

- Tasneef Z, Dinesh K, Bhavna S, NadeemS, Kiran B, Shabab A. Dietary risk factors for colorectal cancer: A hospital-based case–control study. Cancer Research, Statistics, and Treatment 2021;4:479-485.

- Markellos C, Ourailidou M, Gavriatopoulou M, Halvatsiotis P, Sergentanis T.N, Psaltopoulou T. Olive oil intake and cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2021; 17:e0261649.

- Afroz M, Zihad S.M,Jamal Uddin Sh, Rouf R,Rahman Md.S, Islam Md.T, et al. A systematic review on antioxidant and antiinflammatory activity of Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.) oil and further confirmation of antiinflammatory activity by chemical profiling and molecular docking. Phytotherapy Research 2019; 33: 1–24.

- IARC monographs on the identification of carcinogenic hazards to humans, WHO. https://monographs.iarc.who.int/list-of-classifications.

- Batlle J, Gracia-Lavedan E, Romaguera D, Castaño-Vinyals G, Kogevinas M, Romaguera D et al. Meat intake, cooking methods and doneness and risk of colorectal tumours in the Spanish multicase-control study (MCC-Spain). Eur J Nutr 2018; 57:643–653.

- Emadi A, Jayedi A, Mirmohammadkhani M, Abdolshahi A. Aflatoxin reduction in nuts by roasting, irradiation and fumigation: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 2022; 62:5056-5066.

- Henning S.M, Yang J,Shao P, Lee R, Huang J, Ly A, et al. Health benefit of vegetable/fruit juice-based diet: Role of microbiome. Sci Rep 2017; 7:2167.

- Wu Z.W, Chen J.L, Li H, Su K, Han Y. Different types of fruit intake and colorectal cancer risk: A meta-analysis of observational studies. World J Gastroenterol 2023; 29:2679-2700.

- Agagündüz D,Sahin T.O, Yilmaz B,Ekenci K.D,Özer S.D,Capasso R. Cruciferous Vegetables and Their Bioactive Metabolites: from Prevention to Novel Therapies of Colorectal Cancer. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2022 Apr 11:2022:1534083.

- Sartini M, Bragazzi N.L, Spagnolo A.M, Schinca E, Ottria G, Dupont C, et al. Coffee Consumption and Risk of Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Prospective Studies. Nutrients 2019; 11:694.

- Zhu M, Lu D, Ouyang J, Zhou F, Huang P, Gu B, et al. Tea consumption and colorectal cancer risk: a meta analysis of prospective cohort studies. Eur J Nutr 2020; 59:3603-3615.

- De S, Paul S,Manna A, Majumder C, Pal K, Casarcia N et al. Phenolic Phytochemicals for Prevention and Treatment of Colorectal Cancer: A Critical Evaluation of In Vivo Studies. Cancers 2023; 15:993

- Yu Hua Li, Niu Y.B, Sun Y,Zhang F, Liu C.X, Fan L, et al Role of phytochemicals in colorectal cancer prevention. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21:9262-9272

- Yi Yu, Xiaoli Jing, Hui Li, Zhao, Wang D, et al. Soy isoflavone consumption and colorectal cancer risk: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2016; 6:25939.

- Qazi,Siddiqui J.A, Jahan R, Chaudhary S, Walker L.A, Sayed Z, et al. Emerging therapeutic potential of graviola and its constituents in cancers. Carcinogenesis 2018; 39: 522–533.

- Parekh S,Soni A. arbor-tristis N. Comprehensive review on its pharmacological, antioxidant, and anticancer activities. Journal of Applied Biology & Biotechnology 2020; 8:95-104.

- Kumar M, Tomar M, Amarowicz R, Saurabh V, Nair S, Maheshwari C, et al. Guava (Psidium guajava L.) Leaves: Nutritional Composition, Phytochemical Profile, and Health-Promoting Bioactivities. Foods 2021; 10:752.

- Devi H.S, Chanu D.K, Singh NB, Chaudhary SK, Keithellakpam OS, Singh KB, et al. Chemical Profiling and Therapeutic Evaluation of Standardized Hydroalcoholic Extracts of Terminalia chebula Fruits Collected from Different Locations in Manipur against Colorectal Cancer. Molecules2023;28:2901.

- Shen L,Li C, Li N, Shen L, Li Z. Abnormal bowel movement frequency increases the risk of rectal cancer:evidence from cohort studies with one million people. Bioscience Reports 2020; 40:BSR20200355.

- Physical activity and cancer, NCI. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/obesity/physical-activity-fact-sheet 2020 [accessed on Feb 18, 2022]

- Yoga poses for IBS, Yoga International. https://yogainternational.com/article/view/5-yoga-poses-for-ibs-irritable-bowel-syndrome/ [accessed on Mar 15, 2022]

- D’Silva A, Marshall D.A, Vallance J.K, Nasser Y,Rajagopalan V,Szostakiwskyj J.H et al. Meditation and Yoga for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2023;118:2:329–337.

- “Detoxes” and “Cleanses”: What You Need To Know, National center for complimentary and integrative health. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/detoxes-and-cleanses-what-you-need-to-know 2019 [accessed on Jun 2022].

- Chapelle N, Martel M, Toes- Zoutendijk E, Barkun A.N, Bardou M. Recent advances in clinical practice: colorectal cancer chemoprevention in the average-risk population. Gut 2020; 69: 2244–2255.

- Jackson K, Samaddar S,Markiewicz M.A,Bansal A. Vaccination-Based Immunoprevention of Colorectal Tumors: A Primer for the Clinician. J Clin Gastroenterol 2023; 57:246-252.

- Veettil S.K, Wong T.Y, Loo Y.S, Playdon M.C,Lai N.M, Giovannucci E.L, et al. Role of Diet in Colorectal Cancer Incidence. JAMA Network Open 2021; 4:e2037341.

- Switalski J, Tatara T, Wnuk K, Miazga W, Karouda D, Matera A, et al. 2022. Clinical Effectiveness of Faecal Immunochemical Test in the Early Detection of Colorectal Cancer: An Umbrella Review. Cancers. 14:4391.

- González-Vallinas M, González-Castejón M, Rodríguez-Casado A, Molina A.R.Dietary phytochemicals in cancer prevention and therapy: a complementary approach with promising perspectives. Nutrition Reviews 2023; 71:585–599.

- Suganya P, Sindhu R, Prashanthy M, Rajmohan M, Prabu D, Dinesh D, et al. 2021. Does coconut oil combat Streptococcus mutans: A systematic review. Drug and cell therapies in Hematology. 10:1805–1811.

|