|

Sudhir Maharshi1, Sumit Yadav1, Abhishek Bhatia1, Kamlesh Kumar Sharma1, Naresh Kumar Mangalhara2, Rupesh Pokharna1, Sandeep Nijhawan1, Shyam Sunder Sharma1 1Department of Gastroenterology, 2Department of Radiology, SMS Medical College and Hospitals, Jaipur, India.

Corresponding Author:

Prof. Sudhir Maharshi Email: sudhir.maharshi@gmail.com

Abstract

Background and Objectives: Visceral larva migrans (VLM) is a systemic presentation of migrated nematodal larvae through human viscera. It is usually under diagnosed and not kept as a differential diagnosis of hepatic space-occupying lesions (SOL). Only a few case reports and short case series are available in the literature. Majority of these cases are still managed as amoebic or pyogenic hepatic abscesses. Here, we report six cases diagnosed as VLM. Methods: We analyzed six patients who presented to us with non-resolving fever and pain in the abdomen and had atypical SOL on ultrasound abdomen. Appropriate blood investigations and relevant serologies were sent. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/triple-phase computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen was done to characterize the lesions. The liver SOL underwent ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) for histopathological examination. Results: All the six patients had peripheral eosinophilia. MRI abdomen revealed multiple conglomerated T1 hypointense and T2 hyperintense cystic lesions with diffusion restriction, suggestive of abscesses. FNAC and histopathological examination revealed eosinophilic abscesses along with Charcot Leyden crystals. Toxocara canis serology was positive in all six patients, establishing hepatic VLM. All six patients had an excellent response to medical therapy. Conclusion: Hepatic VLM should be contemplated as one of the differential diagnoses of multiple liver nodules or abscesses. MRI abdomen, cytology/histology, serology and clinical-radiological correlation help in diagnosis.

|

Introduction

Visceral larva migrans (VLM) is a systemic presentation of migrated nematodal larvae through human viscera. The liver is most commonly affected because of portal venous blood supply.1 It is usually underdiagnosed and rarely kept in the differential diagnosis of hepatic space-occupying lesions (SOLs). This entity should also be considered in the differentials of patients with sustained eosinophilia showing typical imaging findings. Imaging findings are subtle and must be differentiated from other close entities. Diagnosis requires a strong clinical suspicion, serology, radiology such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)/computed tomography (CT) abdomen, and clinical-radiological correlation. There are only a few case reports and short case series available in the literature on VLM.1-7 In clinical practice, the majority of cases are still managed as amoebic or pyogenic hepatic abscesses. Here, we are reporting six cases of VLM, who presented to us with non-resolving pain in the abdomen, fever, and persistent liver SOL with eosinophilia.

Materials & Methods

This study was carried out in the Gastroenterology department in a tertiary care center between July 2022 and June 2023. The records of six patients of VLM were reviewed. These patients presented to us with complaints of fever, pain in the abdomen, malaise, and other constitutional symptoms. They had atypical SOL in the liver on ultrasonography (USG) and/or CT abdomen and were being treated as liver abscesses with antibiotics and nitroimidazole drugs in the past with non-resolution of symptoms. Study patient’s detailed history, clinical examination findings and laboratory tests comprising a hemogram, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, kidney function test, liver function test, electrolytes, and a plain abdomen radiograph were reviewed. Other specific blood investigations, including alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), immunoglobulin levels, and serologies (amoebic, hydatid, and Toxocara canis) were also noted. Triple-phase CT abdomen was done to characterize the lesions, and if needed, a triple-phase MRI abdomen with diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) was done for further details to achieve a definite diagnosis. The USG-guided fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of liver SOL was done for histopathological examination. After diagnosis, all six patients were given albendazole 400 mg twice daily for four weeks, along with antihistaminic drugs and other supportive treatment, which were continued for three months. These patients were followed up for three months clinically to confirm the resolution of symptoms and lesions. Informed consent in writing was taken from the subjects and their relatives to use the data and publish it for scientific purposes in an anonymized manner.

Results

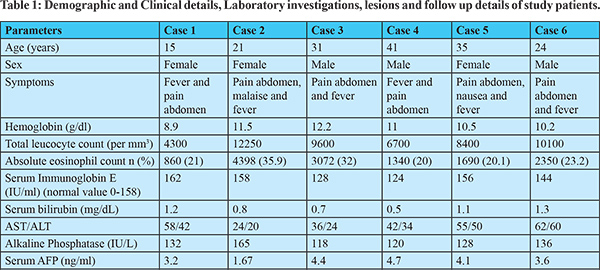

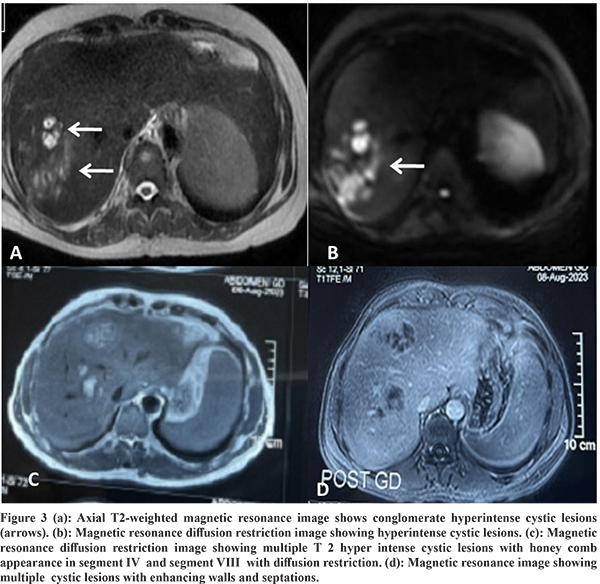

Demographics and clinical presentation: Six patients median age 27.5 years (range15-41) were included in the study with male to female ratio of 1:1. Presenting symptoms in most of the patients were fever, pain in the right hypochondrium and associated malaise in one patient for 2-6 weeks. Most of the patients had received fluoroquinolones and nitroimidazole antibiotics for four weeks without improvement in symptoms. On examination, these patients had pallor and hepatomegaly without palpable spleen or lymph node. The baseline demographic and clinical presentation of all the six patients are given in Table 1. Two patients had history of pets (dogs) in house while three patients were non-vegetarian by diet.

Laboratory Features: The median hemoglobin of the study patients was 10.7 g/dl (range 8.9-12.2), absolute eosinophil count was 2020 cell/mcL (range 860-4398) and serum immunoglobin E level was 150 IU/ml (range 124-162). Hydatid and amoebic serology were negative in all the patients, while Toxocara serology by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) came out to be positive in all. Peripheral smear showed eosinophilia in all the patients. All the patients also underwent USG-guided FNAC of hepatic lesions, which showed degenerated, mixed inflammatory cells primarily consisting of eosinophils along with necrosis and a considerable number of Charcot Leyden crystals, with no parasites observed in the smears as shown in (Figure 1d). The detail of laboratory features of all the six patients are given in Table 1.

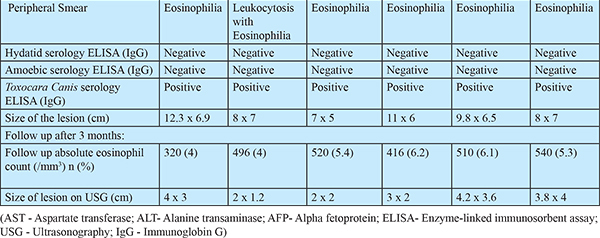

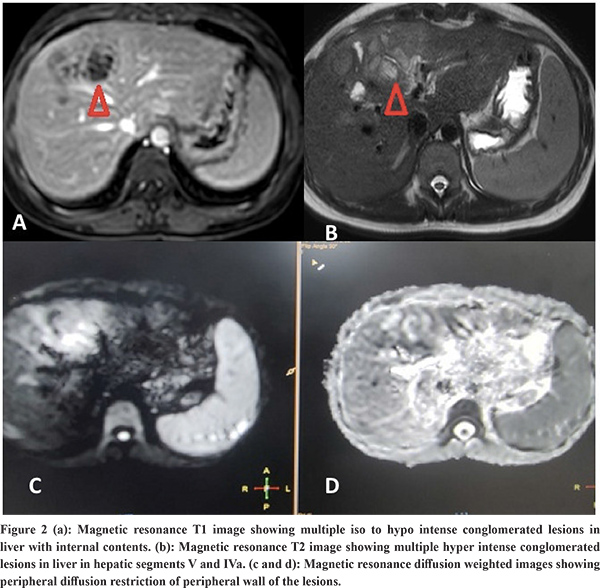

Imaging Features: Abdominal ultrasound showed a multi-cystic hypoechoic lesion in both hepatic lobes with internal echoes and vascularity in all the patients. Triple-phase abdominal CT showed several round, thick-walled lesions and internal septations (Figure 1a). For further characterization of lesions, a triple-phase MRI of the abdomen was done, which showed multiple conglomerated multiloculated cystic lesions showing T1 hypointense and T2 hyperintense signal intensity with internal septations and honey combing with restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted (DW) images (Figure 1b, 1c, 2 and 3). The lesions showed progressive enhancement of the peripheral wall and internal septations, favoring atypical hepatic abscess or VLM. Because of imaging findings and peripheral eosinophilia, a provisional diagnosis of hepatic VLM was considered. The detail of imaging features are given in Table 1 and the given size of lesions is the size of largest lesion in the individual patients.

Treatment and follow-up: Based on available investigations, hepatic VLM was diagnosed. The subjects were given oral albendazole 400mg twice a day for four weeks. On a follow-up visit at the end of 3 months, all the patients had a decrease in the percentage of eosinophil counts and a reduction in the size of hepatic lesions on USG along with an improvement in clinical symptoms as shown in Table 1.

Discussion

The VLM is a syndrome distinguished by chronic eosinophilia, eosinophil-rich hepatic granulomatous lesions, and some degree of lung involvement. It should be considered as one of the differential diagnoses of liver abscesses, as shown in a recently published small case series.8 The etiological agent is larvae of genus Toxocara, subspecies Toxocara canis or catis.2 It occurs due to the migration of second-stage larvae through the human viscera. Cats and dogs are the most typical primary hosts for the disease-causing nematodes for Toxocara catis and Toxocara canis, respectively.1 The estimated seroprevalence of human toxocariasis is 19% worldwide and 19.6% in India.9 Toxocara canis infection in humans occurs by ingesting eggs from the soil or consuming undercooked animal liver with encapsulated larvae. The ingested eggs and larvae develop into migratory larvae, and released into the small intestine. From here, they pass through the intestinal wall into the portal venous system and spread throughout the body to infest various organs like the liver, lungs, brain, heart, eyes, etc. The liver is the most typical organ to be involved because it has a rich blood supply. The characteristic clinical triad of toxocariasis is unexplained eosinophilia, hepatic or pulmonary lesions on imaging, and animal meat intake history.3 The VLM has several other non-specific symptoms, including generalized malaise, lethargy, and cough.4 Heavy infestation can result in pain in the abdomen, fever, hepatomegaly, and significant eosinophilia, along with involvement in other organs like the lungs, heart (myocarditis), central nervous system (causing dysfunction, seizures, and coma), and eyes (endophthalmitis). However, mild infestations are usually asymptomatic, with normal or mildly elevated eosinophil counts and Toxocara titers.5 The pathogenesis of liver penetration is likely because of an allergic reaction to the larva. Eosinophil counts in the blood are considerably increased in the subjects with liver lesions. However, eosinophilia does not relate to the number of liver lesions on imaging.6 Any patient with unexplained fever and eosinophilia with liver SOL should be suspected of suffering from VLM. The VLM is diagnosed based on abdominal imaging features and immunological tests. Other markers of infection comprise hypergammaglobulinemia and an increased isohemagglutinin titer. Hence, a cluster of clinical symptoms mentioned above, raised eosinophils in the blood, and a positive serology firmly suggests VLM.10-11 Chang et al. explained VLM's ultrasound and CT features based on an analysis of 70 hepatic VLM cases. On USG, the lesions appeared as several hypoechoic conglomerating lesions with varying internal echoes. The lesions of VLM are challenging to differentiate from evolving or residual hepatic abscesses. On contrast CT, these 1.0-1.5 cm, several angular or trapezoid lesions appeared as non-subcapsular hypodense lesions. These lesions are best visualized in the portal phase with little or no peripheral enhancement or surrounding edema.6 In our study all six patients also showed similar findings, as mentioned earlier. Kim et al. demonstrated characteristic T1 weighted hypo-iso intensity and T2 weighted hyperintensity of the lesions.12 The MRI features include the well-defined hyperintense rim of the abscesses and restriction of these lesions on apparent diffusion coefficient maps corresponding to the diffusion images.13 Our study patients also revealed similar MRI findings as described in the results. The differentiation of VLM from other liver SOLs like HCC, metastasis, and focal eosinophilic infiltrate is usually challenging. It is differentiated from metastatic lesions by observing for fuzzy margins and elliptical-shaped, uniformly sized lesions of 1-2 cm. The eosinophilic abscesses are commonly seen in the portal venous phase, which may further alter in size and position, specifically to larva migration in the liver, as opposed to metastatic lesions, which are fixed in location and primarily enhance on the arterial phase.6,14,15 Few VLM lesions can be differentiated from HCC by enhancement in the hepatic arterial phase but lack of washout in equilibrium and delayed phases. Echinococcosis is another differential diagnosis that rarely leads to eosinophilia, but these lesions are primarily present as masses and may reveal daughter cysts and/or membranes.14 Focal eosinophilic liver disease is a less commonly observed disease that is usually linked with parasites, allergies, malignant conditions, hypersensitive drug reactions, and hypereosinophilic syndrome.16 Focal eosinophilic infiltrates are differentiated with MRI on DWI. Some neoplasms like lymphoma, leukemia, and carcinoma such as HCC, gastric carcinoma, and colonic carcinoma can also be associated with focal eosinophilic infiltrates and peripheral eosinophilia.17 Molecular diagnostics are helpful in these cases to characterize liver lesions. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequencing techniques can be helpful here to support the ELISA-based immune diagnosis and for focused verification of radiological findings because they are highly sensitive, specific, and rapid.18 The preferred drug for VLM is albendazole.

Conclusions

In conclusion, hepatic VLM should also be a differential in patients with sustained eosinophilia, showing the typical imaging findings. The imaging findings are usually subtle and must be differentiated from other close entities. Diagnosis requires a strong clinical suspicion, serology, radiology such as MRI/CT abdomen, and clinical-radiological correlation along with cytology.

References - Beaver PC,Syndrer CH, Carrera GM, Dent JH, Lafferty JW. Chronic eosinophilia due to visceral larva migrans: report of three cases. Pediatrics. 1952;9:7–9.

- Beaver PC. Parasitological reviews: larva migrans.Exp Parasitol. 1956;5:587–621.

- Lim JH, Lee KS. Eosinophilic infiltration in Korea: idiopathic? Korean J Radiol. 2006;7:4–6.

- Van Kanpen F, Buijs J, Kortbeek LM, Ljungstron I. Larva migrans syndrome: toxocara,ascaris,or both?Lancet. 1992;340:550–1.

- KaplanKJ,GoodmanZD,IshakKG.Eosinophilicgranulomaoftheliver:acharacteristic lesion with relationship to visceral larva migrans. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001; 25:1316-21.

- Chang S, Lim JH, Choi D, Park CK, Known NH, Cho SY, et al. Hepatic visceral larva migrans of toxocaracanis: CTandsonographicfindings.AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:W622–9.

- Desai SN, Pargewar SS, Agrawal N, Bihari C, Rajesh S. Hepatic visceral larva migrans with atypical manifestations : a report of three cases. Trop Gastroenterol. 2018; 39: 211-14.

- Kothalkar S, Mathur A, Elhence A, Verma R, Ghosal UC. Hepatic visceral larva migrans : a case series. Trop Paracetol. 2023; 13: 126-8.

- Rostami A, Riahi SM, Holland CV, Taghipour A, Khalili-fomeshi M, Fakhri Y, et al. Seroprevalence estimate for toxocariasis in people worldwide: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019; 13(12):e0007809.

- Despommier D. Toxocariasis: clinical aspects, epidemiology, medical ecology, and molecular aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003; 16:265-72.

- BhatiaV, Sarin SK. Hepatic visceral larva migrans:evolution of the lesion,diagnosis, and role of high dose albendazole therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:624-7.

- Kim YK, Kim CS, Moon WS, Cho BH, Lee SY, Lee JM. MRI findings of focal eosinophilic liver diseases.AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1541-8

- Laroia ST, Rastogi A, Bihari C, Sarin SK. Hepatic visceral larva migrans, a resilient entity on imaging: Experience froma tertiary liver center. Trop Parasitol. 2016; 6:56-68.

- Srinivas MR, Deepashri B, Lakshmeesha MT. Imaging Spectrum of Hydatid Disease: Usual and Unusual Locations. Pol J Radiol. 2016;81:190-205.

- Ahn SJ, Choi JY, Kim KA, Kim MJ, Baek SE, Kim JH, etal. Focal eosinophilic infiltration of the liver: gadoxeticacid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging and diffusion-weighted imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2011;35:81-5.

- Kim GB Kwon JH, Kang DS. Hypereosinophilic syndrome: imaging findings in patients with hepatic involvement. AJR Am J Roentgenol.1993;161:577-80.

- Wasserman SI, Goetzl EJ, Ellman L, Austen KF. Tumor-associated eosinophilotactic factor.NEngl JMed. 1974;21:420-4.

- Li MW, Lin RQ, Chen HH, Saini RA, Song HQ, Zhu XQ. PCR tools for the verification of the specific identity of ascaridoid nematodes from dogs and cats. Mol Cell Probes.2007;21:349-54.

|