48uep6bbphidvals|431

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) is a rare condition

seen in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. It causes significant morbidity, complicates stomal care and prolongs

the duration of treatment. The management of this condition is difficult and requires a multidisciplinary approach involving

the gastroenterologist, dermatologist, surgeon, and stomal

therapist. We report 2 patients of PPG with severe ulcerative

colitis. Through these cases we attempt to illustrate the varying response these patients may have to high dose steroid therapy

which may necessitate an earlier recourse to completion proctectomy or colectomy.

Case 1

A twenty-one year old man, a known case of chronic steroiddependant

ulcerative colitis, underwent subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy and a Hartmann’s rectal pouch procedure.

Following surgery, the steroids were gradually tapered over a

period of 1 month. Four months following complete withdrawal

of steroids, the patient developed a painful peristomal ulcer (6

cm by 5 cm) (Figure 1a). There were no constitutional

symptoms, hematochezia, or extra-intestinal manifestations.

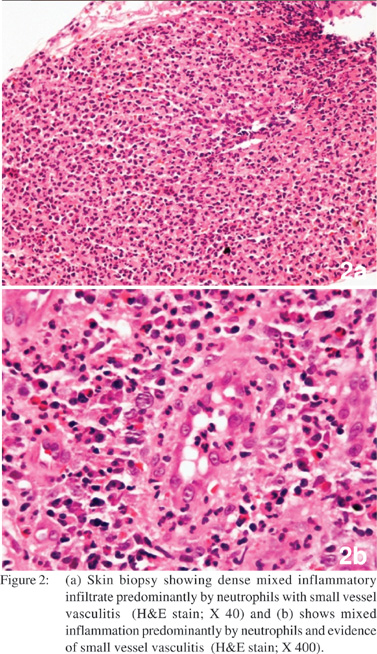

The skin biopsy done showed surface ulceration with dense

mixed inflammatory infiltrate (predominantly neutrophils), and evidence of small vessel vasculitis, with no microorganisms

seen on special stains which was consistent with the clinical

diagnosis of pyoderma gangrenosum (Figures 2a & 2b). The

patient was re-started on oral steroids (prednisolone 40 mg per

day). Within 1 week of starting steroids, the lesions showed

signs of healing (Figure 1b). After 1 month of steroid treatment,

the ulcer had completely healed. This patient subsequently

underwent completion proctectomy with an ileal J-pouch anal

anastomosis (double stapled technique) and a covering loop

ileostomy. The patient is now awaiting ileostomy closure and

is on regular follow up at 2 weekly intervals. Barring an episode

of adhesive intestinal obstruction which was managed

conservatively, the patient is doing well, the steroids have been

tapered, and all operative wounds have healed well with no recurrence of the ulcer.

Case 2

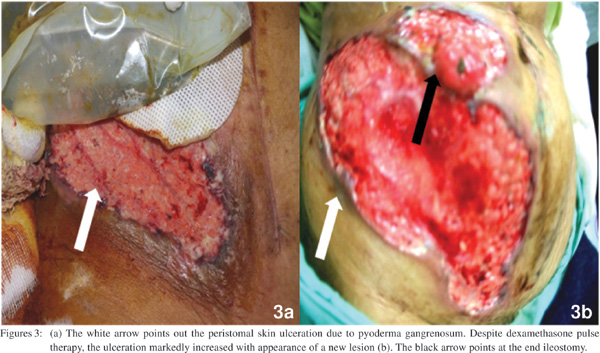

Three months following subtotal colectomy for a severe acute exacerbation of ulcerative colitis (refractory to intensive steroid regimen), a 35-year old lady presented with a painful ulcer (8

cm by 4 cm) around the ileostomy (Figure 3a). She had high grade fever, decreased appetite and complained of increased

rectal bleeding. Proctoscopic examination revealed an inflamed rectal mucosa with ulcerations and pseudopolyps. She had

anemia and a raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR). A skin biopsy showed features consistent with a diagnosis of

pyoderma gangrenosum. A few days later she developed

another similar lesion on her shin. She was started on

prednisolone (40 mg per day) and received 3 pulses of

dexamethasone (100 mg per day for 5 days every 4 weeks).

Following initial improvement, the peristomal lesion

subsequently worsened with enlargement in size (13 cm by 17

cm) and appearance of a new lesion (Figure 3b). There was

difficulty in applying ileostomy appliance, and the ileostomy

effluent was managed by frequent changes of pads. She also

had persistent rectal bleeding despite being on systemic steroids and topical mesalamine treatment. In view of a relapse

of the pyoderma gangrenosum, and a negligible response to

high dose steroids, she underwent a completion proctectomy

with an ileal J-pouch anal anastomosis (double stapled

technique) and a covering loop ileostomy. Within a month of

the operative procedure, the skin lesions (both peristomal and

shin) healed completely (Figures 4a & 4b). She subsequently

underwent closure of the ileostomy. At the last follow-up, 3

years following her ileostomy closure, the patient was doing

well with good pouch function and no recurrence of the skin

lesions.

Discussion

Peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum (PPG) is a disabling

condition in patients with a stoma. The lesion begins as small

erythematous papules that rapidly spread concentrically, coalesce and subsequently develop central ulceration and

necrosis. The mature lesions have well-defined, undermined,

violaceous border and are very painful.[1]

The exact incidence of PPG is not known. We diagnosed

PPG in 2 of the 250 patients who underwent surgery for

inflammatory bowel disease in our unit. It is possible that the incidence of PPG is higher than reported because PPG is often under-diagnosed or misdiagnosed as stitch abscess, contact

dermatitis, irritation from leaking feces or urine, extension of underlying Crohn’s disease or a wound infection. A high index

of suspicion and familiarity with the appearance of the lesion is needed to make a diagnosis.

The cause of PPG is still debated. The name pyoderma

gangrenosum reflects the historical view of the disease as an

infectious process, but the characteristic lesions are sterile.

Most patients relate the development of the skin lesions to

trauma in the peristomal area. It has been suggested that in

patients with IBD, the development of PPG may reflect the

severity of intestinal disease.[2] The PPG lesions in our first

patient appeared after the withdrawal of steroids. The second

patient had undergone subtotal colectomy for an acute

exacerbation that was refractory to intensive medical

management with steroids. The subsequent appearance and

worsening of pyoderma gangrenosum in this patient, correlated

with worsening of the disease in rectal stump (increased

bleeding per rectum, inflamed rectal mucosa with ulcerations,

anemia and raised ESR).

The time to onset for PPG is variable and may range from a

few months to up to many years. The rapidity of progression is considered to be the hallmark of the disease.[3] Our patients

developed the lesions 3-4 months following creation of the ileostomy and showed rapid progression. The lesions made

stoma care very difficult and labor intensive. In the second

patient, the peristomal lesion was so large that the stomal

appliance could not be applied and the local care of the wound

and stoma was done by frequent change of dressing pads.

The best therapy for PPG is not known. Topical treatment

with steroids, antibiotics or other wound care agents have

been described.[4] However, these modalities may not be suitable

for larger lesions and have no impact on the underlying

intestinal disease.

The other options are to treat the underlying active

inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. A few reports

describe the use of systemic therapy with high dose steroids,

antibiotics, dapsone, cyclosporine, and infliximab.[5,6,7] Steroid

pulse therapy has also been reported to be effective in some

cases.[8] We managed our first patient with systemic steroids

and he showed a good clinical response. The second patient

was initially managed with prednisolone (40 mg/day) and 3

pulses of dexamethasone pulse therapy (100 mg/day for 5 days

every 4 weeks). However, her skin lesions were refractory to

this treatment. Infliximab was not considered because of its high cost.

The surgical treatment options for PPG include stoma

revision and relocation but these may have failure rates as

high as 40%-100%.[9] Removal of the actively diseased intestinal

segment may be a treatment option in these patients and may

result in healing of the skin lesion.[10] The PPG in our second

patient were refractory to steroids but showed prompt healing

following surgical removal of the diseased rectum.

References

- Callen JP: Pyoderma gangrenosum. Lancet. 1998;351:581–5.

- Hughes AP, Jackson JM, Callen JP: Clinical features and treatment

of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA. 2000;284:1546–8.

- Holt PJ: The current status of pyoderma gangrenosum. Clin Exp

Dermatol. 1979;4:509–16.

- Nybaek H, Olsen AG, Karlsmark T, Jemec GB: Topical therapy for peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. J Cutan Med Surg.

2004;8:220–3.

- Funayama Y, Kumagai E, Takahashi K, Fukushima K, Sasaki I:

Early diagnosis and early corticosteroid administration improves

healing of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum in inflammatory

bowel disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:311–4.

- Poritz LS, Lebo MA, Bobb AD, Ardell CM, Koltun WA: Management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. J Am Coll

Surg. 2008;206:311–5.

- Sapienza MS, Cohen S, Dimarino AJ: Treatment of pyoderma

gangrenosum with infliximab in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci.

2004;49:1454–7.

- Galun E, Flugelman MY, Rachmilewitz D: Pyoderma gangrenosum complicating ulcerative colitis: successful treatment with

methylprednisolone pulse therapy and dapsone. Am J

Gastroenterol. 1986;81:988–9.

- Kiran RP, O’Brien-Ermlich B, Achkar JP, Fazio VW, Delaney

CP: Management of peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum. Dis Colon

Rectum. 2005;48:1397–403.

- Talansky AL, Meyers S, Greenstein AJ, Janowitz HD: Does intestinal resection heal the pyoderma gangrenosum of inflammatory bowel disease? J Clin Gastroenterol.

1983; 5:207–10.