48uep6bbphidvals|442

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Hemobilia is a complex clinical problem and occurs when there

is an abnormal communication between the vascular and biliary

system. Although it was first described in 1654 by Francis

Glisson, it was not until 1948[1] that Sandblom gave a detailed

description of hemobilia. Profuse haemorrhage into the biliary

tract i.e. major hemobilia is rare but can lead to morbidity and

mortality. Although there is significant data available from the

west, there is little published information on this condition

from India. With the increasing number of invasive hepatobiliary

interventions being performed, the incidence of hemobilia is

likely to rise. The aim of this study was to analyze the spectrum,

clinical presentation and management of major hemobilia in a

tertiary referral centre from western India.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of 22 patients with major hemobilia

was undertaken over a 5-year period. There were 16 males and

6 females with a mean age of 39 years (range: 13-74 years).

Major hemobilia was defined as bleeding in the biliary tree

causing overt gastrointestinal bleeding in the form of

haematemesis/melena associated with a fall in haemoglobin of>3 gm/dl. Cholangitis was diagnosed when there was associated

fever and leukocytosis. All patients were resuscitated with

intravenous fluids and covered with broad spectrum antibiotics.

Upper gastrointestinal (UGI) endoscopy was performed in case

of doubt about the source of bleed.

Results

The main presenting symptoms were melena in 20 patients and

hemetemesis (with melena) in 8 patients. Seventeen patients

needed blood transfusions (mean: 3 units, range: 1-5 units).

The mean drop in hemoglobin was 5 gm/dl (range: 3–7 gm/dl).

Eight patients presented with associated cholangitis and 3 of

these developed septic shock.Thirteen patients (59%)

developed hemobilia secondary to iatrogenic causes

(percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage 8, post

laparoscopic cholecystectomy 3, endoscopic retrograde

cholangiopancreatography 1, and liver biopsy 1). There was

history of trauma in 6 patients and 3 patients bled from liver

tumors. The hemobilia was seen immediately in the endoscopic

papillotomy patient, but developed after a mean of 6 days in

the post percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD)

group and 11 days in the trauma group. Four out of the six

patients with trauma had undergone laparotomy elsewhere,

with 3 requiring suturing of liver lacerations.

Eight patients had an UGI endoscopy and fresh blood was

seen in the second part of duodenum in five. Ultrasound

examination with Doppler was performed in 10 patients, which

revealed filling defects in the biliary tree suggestive of clots (3

patients), pseudoaneurysm (6 patients) and was normal in one

patient. Doppler was performed in some cases elsewhere before

referral.

Abdominal angiography (celiac & SMA) was performed in

20 out of the 22 patients. Angiography was not done in two

patients (one patient had venous bled from portal biliopathy

after stone extraction and the other underwent surgery directly

for liver tumor, since the bleeding had stopped). Angiography

revealed pseudoaneurysm of the right hepatic artery or its

branches in 14 patients, left hepatic artery in 2, an arterio-biliary

fistula in 1, tumor blush in 1 and the source could not be located

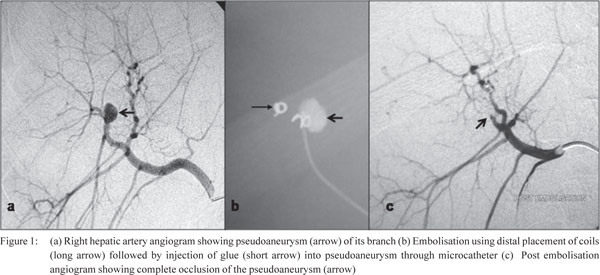

in 2 patients. Figure 1 (a, b, c) shows traumatic pseudoaneurysm

of a branch of right hepatic artery along with its embolisation.

Seventeen patients were treated with radiological intervention

in the form of embolisation (coils and/or glue-16, and

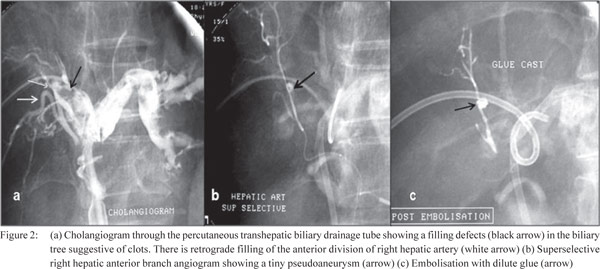

chemoembolisation with doxorubicin –1). Figure 2 (a, b, c)

shows a PTBD induced psuedoaneurysm with

angioembolisation. Sixteen patients responded immediately to

embolisation. One patient required two sessions, as he had an

accessory right hepatic artery arising from the superior

mesenteric artery which was the cause of bleed and was missed

on the initial angiogram. Three patients required surgery (liver

resection for hepatocellular carcinoma – 2, laparotomy for

bleeding from a portal biliopathy – 1) and two were managed

conservatively. The cholangitis did not need separate drainage

but settled with control of the hemobilia.

There were two early deaths (mortality: 9%). One patient

with portal cavernoma died of massive venous bleed, which

could not be controlled at laparotomy and the other due to

liver failure 1 week after hemoembolisation. The other two

patients with liver tumors died during the follow up due to

extensive disease. Out of the eight patients who had undergone

PTBD for hilar cholangiocarcinoma (4 preoperative biliary

drainage, 4 palliative drainage and stenting), 4 were lost to

follow up and 4 underwent definitive surgery once the bilirubin

was < 3 mg/dl. Two patients in the post cholecystectomy group

underwent definitive biliary repair after 3 months. Table 1

summarizes the etiology, angiography findings, management

and outcome of our patients.

Discussion

In the first large review of hemobilia consisting of 545 patients

published by Sandblom in 1972,[2] trauma was noted as the most

common causative factor. In developed countries the increasing

use of interventional procedures has now resulted in iatrogenic

injury in being the most common cause.[3]

The incidence of iatrogenic hemobilia following liver biopsy,

percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography and PTBD is 1%[4]

and 2-10%[5,6] respectively. The commonest iatrogenic cause of

hemobilia in our series was secondary to PTBD procedures,

which was seen after mean of 6 days. A combination of pressure

from a stiff catheter and local sepsis causes erosion of the

blood vessel wall, leading to formation of a pseudoaneurysm in close proximity to the bile duct, causing hemobilia on rupture.

The incidence of blunt liver injury causing hemobilia is

about 2.5 - 3%.[7] Out of the 6 patients with liver trauma in our

series, 3 had undergone hepatorrhaphy elsewhere. The frequent

reason is bleeding within the liver substance with intact capsule

or superficial suturing of the injury, with resultant hematoma

rupturing into the biliary tree.[8] The hematoma may also get

infected leading to a mycotic pseudoaneurysm, which may

later erode into the biliary tree. Therefore, while exploring a

liver laceration, precise identification and suturing of vessels

and ducts is important. The trend towards conservative

management of liver injury may be expected to result in an

increase in the incidence of hemobilia.[9] Therefore we believe

that there should be a low threshold for follow up imaging in

this group of patients.

Tumors account for about 6% of all causes of major hemobilia

and malignant tumors outnumber the benign ones.[10,11]

Hepatocellular carcinoma secondary to cirrhosis is the

commonest tumor causing hemobilia.[12] The three tumor

patients in our series represent an interesting group and all of

them had small lesions.

The classic triad of upper abdominal pain, GI bleed and

jaundice,[13] was seen only in a minority of our patients. We

believe that for any patient undergoing hepatobiliary

intervention and subsequently presenting with persistent

abdominal pain with pallor, there should be a low thereshold in

suspecting hemobilia. Side viewing endoscopy can identify

bleeding from the papilla in only 30% of patients.[14] We could

demonstrate fresh blood in the second part of duodenum on

UGI scopy in 62% (5/8 patients). Pseudoaneurysms are noted

as well circumscribed anechoic lesions on ultrasound and

doppler shows a turbulent flow within,[15] as was seen in 60% (6/

10 patients) of our patients. CECT can demonstrate smaller

hematomas, anatomical variations, pseudoaneurysms and

cavitating lesions.[16]

Once hemobilia is strongly suspected, the most useful study

is angiography, which may reveal the precise source of bleed.[17]

It can also be combined with definitive therapy by radiological

intervention. Celiac axis angiography should always be

accompanied with superior mesenteric arteriography because

anomalous/accessory right hepatic artery may originate from

the SMA in almost 20 % of the patients, and was observed in one of our patients. Selective right and left hepatic angiogram

may be performed especially in cases of hemobilia secondary

to PTBD, as nonselective angiograms may miss small

pseudoaneurysms. The angiogram may sometimes appear

normal in the absence of any active bleeding or when there is

no demonstrable lesion. Hence we feel that if bleeding

continues or recurs it may be worth repeating an angiogram.

Angioembolisation has now become the first line of

treatment and involves selective occlusion with permanent

embolic agents like microcoils and cyanoacrylate glue.[18] Coils

induce thrombosis, hence with gross coagulopathy, the vessel

may remain patent. Glue can be used to treat smaller

pseudoaneurysm where coil placement may be difficult. Also it

conforms to the shape of pseudoaneurysm and forms a cast

instantly, even in the presence of coagulopathy, and is much

cheaper as compared to coils. Combination of coil and glue

also can be used.[19] Ideally embolisation distal and proximal to

the pseudoaneurysm is necessary to prevent collateral filling

of the pseudoaneurysm. Alternatively, complete occlusion of

the pseudoaneurysm with coils or glue may be done followed

by proximal occlusion with coils.

Previous reviews and retrospective series have shown the

success rate of transarterial embolisation (TAE) to be in the

range of 80 – 100%.4 We had a success rate of 90%. Failure may

be due to technical reasons or extensive collaterals. Antibiotic

prophylaxis is recommended.[20] Selective embolisation as close

to the pseudoaneurysm or fistula possible is desirable to reduce

the likelihood of both recurrence and hepatic necrosis.

Emergency surgery to control major hemobilia is difficult

and should be avoided, as the results are poor. It may be better

to transfer the patient to a center with angiography facilities

rather than operate. Operative intervention may be required if

radiological expertise is not available, there is failure of TAE, or

manifestation of hepatic sepsis.[21] It involves ligation of the

bleeding vessel and hepatic resections. If bleeding is not

controlled by ligation or there is severe trauma an urgent liver

resection may have to be performed. Our mortality of 9% was

slightly higher than that the 5% reported in literature.[3]

There is paucity of literature regarding the etiology,

management and outcome of hemobilia from India. The

published case reports from India mainly describe hemobilia

following trauma or cholecystectomy.[22,23] In the only published

series by Srivastava et al,[24] the predominant etiology of

hemobilia was liver injury following road traffic accidents.

It highlighted the role of TAE in the management of hemobilia.[24] Our series highlights the changing spectrum of hemobilia from

liver injuries to hepatobiliary interventions in our country,

mirroring the spectrum of the developed world. This could be

due to a referral bias. It also emphasizes the role of angiography

in its diagnosis and management. A high index of suspicion

and timely intervention is important. In India the increasing

incidence of biliary stone disease, as well as increasing

nterventions on the hepatobiliary system are likely to result in

clinicians encountering this problem more frequently.

References

- Sandblom P. Hemorrhage into the biliary tract following trauma; traumatic hemobilia. Surgery. 1948;24:571–86.

- Sandblom P. Hemobilia. Surg Clin Nor Am. 1973;53:1191–201.

- Green MH, Duell RM, Johnson CD, Jamieson NV. Hemobilia. Br J Surg. 2001;88:773–86.

- Yoshida J, Donahue PE, Nyhus LM. Hemobilia: a review of recent experience with a world wide problem. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:448–53.

- Dousset B, Sauvanet A, Bardou M, LegMan P, Vilgrain V, Belghiti J. Selective surgical indications for iatrogenic hemobilia. Surgery. 1997;121:37–41.

- Jeng KS, Ohta I, Yang FS. Reappraisal of the systematic management of complicated hepatolithiasis with bilateral intrahepatic biliary strictures. Arch Surg. 1996;131:141–7.

- Parks RW, Chrysos E, Diamond T. Management of liver trauma. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1121–35.

- Merrell SW, Schneider PD. Hemobilia—evolution of current diagnosis and treatment. West J Med. 1991;155:621–5.

- Carrillo EH, Platz A, Miller FB, Richandran JD, Polk HC Jr.

Non-operative management of blunt hepatic trauma. Br J Surg. 1998;85:461–8.

- Blumgart LH, Fong Y. Surgery of the liver and biliary tracts. W.B. Saunders Company Ltd; 2000.p.1319–39.

- John A, Ramachandran TM, Ashraf S, Nair MS, Devi RS. Carcinoma gall bladder presenting as hemobilia. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1999;l18:88–9.

- Sabiston DC. Textbook of surgery. 6th ed. W.B. Saunders Company Ltd; 2001.p.1056–9.

- Quincke H. Ein fall von aneurysm der leberarterie. Klin Wochenschr. 1871;8:349–51.

- Curet P, Baumer R, Roche A, Grellet J, Mercadier M. Hepatic

hemobilia of traumatic or iatrogenic origin: recent advances in diagnosis and therapy, review of the literature from 1976 to 1981. World J Surg. 1984;8:2–8.

- Sax SL, Athey PA, Lamki N, Cadavid GA. Sonographic finding in traumatic hemobilia: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Clin Ultrasound. 1988;16:29–34.

- Yokota J, Sugimoto T. Clinical significance of peirportal tracking on computed tomographic scan in patients with blunt liver trauma. Am J Surg. 1994;168:247–50.

- Shapiro MJ. The role of the radiologist in the management of gastrointestinal bleeding. Gasroenterol Clin North Am. 1994;23:123–81.

- Wallace S, Giaturco C Anderson JH, GoldsteiN HM, Davis

LJ, Bree RL. Therapeutic vascular occlusion utilizing steel coil technique: clinical applications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1976;127:381–7.

- Yamakado K, Nakatsuka A, Tanaka N, Takano K, Matsumura K, Takeda K. Transcatheter arterial embolisation of ruptured

pseudoaneursym with coil and n-butly cyanoacrylate. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2000;11:66–72.

- Cho KJ, Reuter SR, Schmidt R. Effect of experimental hepatic artery embolisation on hepatic function. Am J Roentgenol. 1976;127:563–7.

- Moodley J, Singh B, Lalloo S, Pershad S, Robbs JV. Non-operative management of hemobilia. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1073–6.

- Bajpai M, Bhatnagar V, Mitra DK, Upadhyaya P. Surgical

management of traumatic hemobilia in children by direct ligation

of the bleeding vessel. J Pediatr Surg. 1989;24:436–7.

- Moses V, Keshava SN, Wann VC, Joseph P, Sitaram V. Cystic

artery pseudoaneurysm after laparoscopic cholecystectomy presenting as haemobilia: a case report. Trop Gastroenterol. 2008;29:107–9.

- Srivastava DN, Sharma S, Pal S, Thulkar S, Seith A, Bandhu S, et

al. Transcatheter arterial embolisation in the management of hemobilia. Abdom Imaging. 2006:31:439–48.