48uep6bbphidvals|447

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Case 1

A 30 year old woman presented with pain and lump in left lower

abdomen of two years duration. She had undergone caesarean

section two years back. Examination revealed pallor and an

intra-abdominal, nontender, firm, irregular lump measuring 10 ×

8 cms with restricted mobility in the left lower abdomen.

Laboratory investigations revealed microcytic hypochromic

anemia. Ultrasonography (USG) of the abdomen was

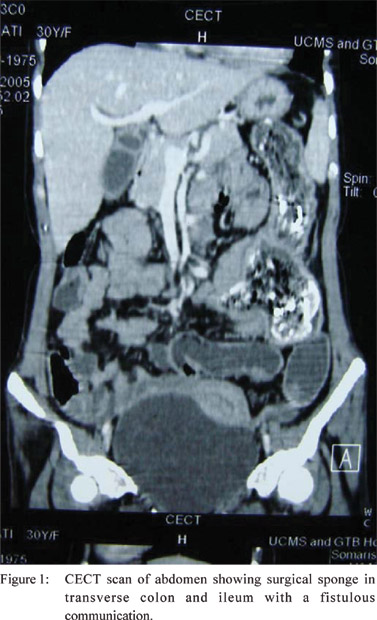

unremarkable. Contrast enhanced CT (CECT) scan of the

abdomen showed a segment of transverse colon adherent to

ileum with surrounding inflammation. An intraluminal, irregular,

calcified mass in the adherent segments of the bowel was seen

incorporating a tortuous, linear, radiopaque density suggestive

of retained surgical sponge (Figure 1).

On laparotomy, a segment of distal ileum was found adherent

to transverse colon. The serosal surfaces of bowel were normal.

There was no ascites, lymphadenopathy, peritoneal deposits

or hepatic metastasis. Involved segments of ileum and

transverse colon were resected and gut continuity was restored

by ileo-ileal and colo-colic anastomosis. On opening the

resected specimen a surgical sponge lying in the lumen of the

ileum and extending into the transverse colon through a

fistulous communication was found. The patient made a good

post-operative recovery and was discharged on 8th postoperative

day.

Case 2

A 16-year-old boy presented with colicky abdominal pain and

bilious vomiting for 4 days. He had undergone laparotomy for

duodenal ulcer perforation 3 months back. General physical

examination was unremarkable except for dehydration.

Abdomen was not distended, scar of the previous surgery

was healthy and visible peristalsis was present. A 4 × 6 cm

firm, tender lump, moving with respiration and with a dull

percussion note was found in the left upper abdomen. Bowel

sounds were exaggerated. Laboratory investigations and Xray

of the abdomen were unremarkable. USG of abdomen

showed dilated bowel loops with hyper echoic mass in the left

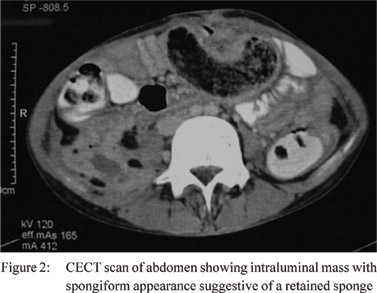

lumbar region. CECT scan of the abdomen showed a mass

with spongiform appearance suggestive of a retained sponge

(Figure 2). Laparotomy revealed distended jejunal loops

proximal to a palpable mass inside the bowel lumen about 1½

foot distal to duodenojejunal flexure. The serosal surfaces of the bowel were normal and distal bowel loops were collapsed.

Enterotomy revealed a retained surgical sponge which was

retrieved and enterotomy incision closed primarily. The patient

made an uneventful recovery.

Discussion

Retained foreign bodies (FB) constitute a mishap in modern

surgery. Most common among these is an accidentally

overlooked surgical sponge.[5] Retained surgical sponge is also

known as gossypiboma [Gossypium (Latin): cotton; oma

(Kiswahili): place of concealment][2], textiloma[1] and cottonoid.

Exact incidence of gossypiboma is unknown as the condition

is considered to be widely underestimated and under reported,

possibly due to fear of medicolegal implications.[1,2,6,7,8] Reported

incidence varies from 1 in 100-3000 for all surgical interventions,

and 1 in 1000-1500 for intra-abdominal operations.[1,2,6]

Gossypiboma has been reported following gynecological,

abdominal, cardiothoracic, orthopedic, and neurosurgical

procedures.[[1,6,9]

The clinical presentation of patients with gossypiboma is

varied which causes considerable diagnostic dilemma.[1] Its

presence should be suspected in any patient where the postoperative

recovery was not smooth or re-admission was

required for persistent symptoms.[6] Gossypiboma may cause

bowel obstruction, perforation, granulomatous peritonitis,

septic syndrome, fistulization to the neighboring organs, or

may mimic a chronic inflammatory process like tuberculosis[10]

and even malignancy.[1,2,11] At times it may be lethal,[3,6] however

it may remain asymptomatic for years.[1,6] Rarely gossypiboma

may migrate to the neighboring organs due to persistent

pressure and subsequent erosion through their wall.[2,3,4] Intestine is the commonest organ where migration occurs, as seen with

both of our patients. This is attributed to the large surface area

and relatively thin wall of the intestine which provides least

resistance to their transmural migration. Other organs where

such migration, although uncommon, has been reported include

urinary bladder, stomach and thorax (through diaphragm).[1]

Radiological features of gossypibomas are variable.

Detection by plain X-ray is difficult,[11] especially when surgical

sponges have not been provided with the radiopaque marker

or when the marker has been fragmented or disintegrated, the

presence of which may aid in diagnosis.[2,6,7] USG may be helpful

and may show an echogenic, complex hypoechoic area, or

cystic mass with acoustic shadow or may be normal[1,12] . CECT

scan is the investigation of choice.[13,14] It may show complex

mass with variable density; calcification; spongiform gas and

radiopaque marker 1(if present), as was seen in patient [1]. In

patient [2], since the sponge lacked a radiopaque marker it was

not visible on radiological investigations. MRI is also

infrequently used for diagnosis.[7] Once diagnosed,

gossypibomas require removal, as morbidity and complications

associated with it are high.[1,2] This usually necessitates

laparotomy. However, alternative methods like laparoscopy,

percutaneous extraction (with or without the help of

interventional radiology)9 and endoscopic procedures have

been reported.[12] Spontaneous extrusion is an extremely rare

favorable outcome.[1,7]

Risk factors leading to gossypiboma include a higher mean

body-mass index, emergency surgery, difficult operative

procedure, surgeon’s fatigue, several sponges sticking

together, poor tracking, change in nursing and surgical teams,

an unplanned change in the operation and unaccountable

human error.[2,12] Although importance of meticulous counting

cannot be over emphasized, cases have been reported in

presence of normal counts.[1,2] Some authors suggest routine

X-ray screening of high-risk patients before they leave the

operating room even if the count is documented to be correct,

although this has not been found to be foolproof.[1,2] thers

have suggested use of sponges held in forceps to prevent

their intra-operative loss.[8] With technological advancement,

the future holds promise for the use of hand held detectors

and scanners that will either supplement or replace manual

counting. Various other innovations like bar coding of

instruments and sponges, radiofrequency identification and

electronic surveillance systems are being developed.[15]

References

- Zantvoord Y, van der Weiden RM, van Hooff MH. Transmural

migration of retained surgical sponges: a systematic review. Obstet

Gynecol Surv. 2008;63:465–71.

- Sarda AK, Pandey D, Neogi S, Dhir U. Postoperative

complications due to a retained surgical sponge. Singapore Med

J. 2007;48:e160–4.

- Falleti J, Somma A, Baldassarre F, Accurso A, D’Ettorre

A, Insabato L. Unexpected autoptic finding in a sudden death:

gossypiboma. Forensic Sci Int. 2010;199:e23–6.

- Kansakar R, Thapa P, Adhikari S. Intraluminal migration of

Gossypiboma without intestinal obstruction for fourteen years.

JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2008;47:136–8.

- Dhillon JS, Park A. Transmural migration of a retained laparotomy

sponge. Am Surg. 2002;68:603–5.

- Alis H, Soylu A, Dolay K, Kalaycý M, Ciltas A. Surgical

intervention may not always be required in gossypiboma with

intraluminal migration. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:6605–7.

- Godara R, Marwah S, Karwasra RK, Goel R, Sen J, Singh R.

Spontaneous transmural migration of surgical sponges. Asian J

Surg. 2006;29:44–5.

- Glockemann K, Fröhlich H, Bernhards J, Büttner D. Peranal

passage of a surgical sponge: fortunate outcome of an

intraoperative oversight. Chirurg. 2005;76:595–8.

- Rappaport W, Haynes K. The retained surgical sponge following

intra-abdominal surgery. A continuing problem. Arch Surg.

1990;125:405–7.

- Sinha SK, Gupta S, Behra A, Khaitan A, Kochhar R, Sharma

BC, et al. Retained surgical sponge: an unusual cause of

malabsorption. Trop Gastroenterol. 1999;20:42–4.

- Haddad R, Judice LF, Chibante A, Ferraz D. Migration of surgical

sponge retained at mediastinoscopy into the trachea. Interact

Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2004;3:637–40.

- Erdil A, Kilciler G, Ates Y, Tuzun A, Gulsen M, Karaeren N, et

al. Transgastric migration of retained intraabdominal surgical

sponge: gossypiboma in the bulbus. Intern Med. 2008;47:613–5.

- Haddad R, Judice LF, Chibante A, Ferraz D. Migration of surgical

sponge retained at mediastinoscopy into the trachea. Interact

Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2004;3:637–40.

- Klariæ Custoviæ R, Krolo I, Marotti M, Babiæ N, Karapanda N. Retained surgical textilomas occur more often during war.

Croat Med J. 2004;45:422–6.

- Gibbs VC. Patient safety practices in operating room: correctsite

surgery and nothing left behind. Surg Clin North Am.

2005;85:1307–19, xiii.

- Kacker R. Retained foreign bodies in the abdominal cavity. In: Roshan Lall Gupta, editors. The medicolegal aspects of Surgery. Ist ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers; 1999. p.176.