Crohn’s disease is a chronic inflammatory condition of the gastrointestinal tract of an unknown etiology, characterized by alternating exacerbations and remissions of intestinal inflammation. A reduced food intake, nutrient malabsorption, enhanced intestinal losses and an altered metabolism often result in an impaired nutritional status as reported in upto 65-75% of these patients.

[1,

2] An altered body composition with deficits in lean and fat mass in these patients, is associated with morbidity, increased susceptibility to infections, gut barrier dysfunction, loss of muscle strength and an overall poor quality of life.

[3] Since appropriate enteral nutrition has a promising role in the treatment of patients with CD, an exact quantification of the extent of nutritional depletion through measurement of body compartments, allows physicians to formulate objective guidelines for the type and amount of nutrition support appropriate for these patients. These calculations are based on the information available on patient’s body protein and fat resources.

[4] So far the characterization of body composition in terms of fat mass (FM) and fat free mass (FFM) has been poorly understood in CD, as studies have yielded equivocal results. Furthermore, there are no reports which have examined this issue among Indian patients. Bioimpedance analysis (BIA) is a simple, quick, portable and inexpensive method for measuring body composition. Hence the present study was planned to assess the body composition of CD patients using BIA and compare the measurements with those in healthy controls.

Methods

Patients

All consecutive patients of Crohn’s disease attending the outpatient and IBD clinic of department of Gastroenterology and human nutrition at AIIMS, were enrolled in the study as per well defined inclusion criteria.

Controls

Hundred age and sex matched healthy individuals comprising of family members of patients with a diagnosis other than IBD, served as controls. None of these controls had any gastrointestinal or systemic disease.

Diagnosis of Crohn’s disease

The diagnosis of CD was based on standard diagnostic criteria which included clinical evaluation in combination with endoscopic, histological and radiological features.

Activity of CD

The severity of CD was assessed by the Crohn’s disease activity index (CDAI).

[5] Patients with a CDAI score <150 were considered to be in clinical remission.

Location of CD

The site of the disease was classified by the modified Montreal classification.

[6]

Exclusion criteria

Patients with any other systemic disease unrelated to CD, that potentially affected the body composition such as endocrine disorders, liver and renal disease were excluded. Pregnant women and patients <18 and >65 were also excluded.

Assessment of body composition

Bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA) is based on the relation between the volume of a conductor and its electrical resistance. Impedance is the opposition of a conductor to the flow of an alternating electrical current which can be measured by passing a small alternating current of <1mA (below the perception of the subject) through the body and measuring the resulting potential difference. Recently leg-to-leg bio-impedance measurement has been developed where a low electrical current is passed between the anterior and posterior electrodes of the system, on which the subject stands bare foot. The bioimpedance relative to the subject’s stature is used to estimate the total body water (TBW), where the TBW is a fixed part of FFM. The FM is computed as the difference between body weight and FFM.

[7]

Bio-impedance was measured using a Tanita TBF-215 legto- leg portable impedance analyzer (Tanita, Japan). This system comprises of two main units. The first unit consists of a platform scale on which stainless steel foot pad electrodes are mounted. While the subject stands on these electrodes an alternating current of 500 µA at 50 kHz is passed through these electrodes and the potential difference is recorded. The second unit is a table top indicator with a digital keyboard through which height and gender is entered into the microcomputer, the body weight and impedance are measured from which the FM, percentage fat and FFM are calculated. Height was measured using the built-in height rod in the instrument. Patients were made to stand on the scale bare foot with minimum clothing, with their hands by their sides. For all patients, 0.5 kg was deducted to account for their clothes. All measurements were made empty stomach after 12 hours of overnight fast, without anyintake of liquids. Three repeat measurements were recorded and the mean value was taken as final.

Assessment of dietary intake

Diet intake was assessed using the 24 hours diet recall method, using standardized set of household measurements of bowls, spoons and glasses of different sizes to assess the amount / portion of food consumed. The intake of macronutrients was calculated by a software called “computerized nutrient evaluation programme” (CNIEP) programmed as per Indian food composition tables published by the Indian Council of Medical Research.

[8]

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS v11.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Data were expressed as number (percentage) and mean+SD (range). The difference in proportion for the categorical data was compared using chi equare test. Comparison between three or more groups was done using ANOVA and two group comparisons were made using Student’s t-test. Bivariate relationships were assessed by Pearson’s correlation. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient and disease characteristics

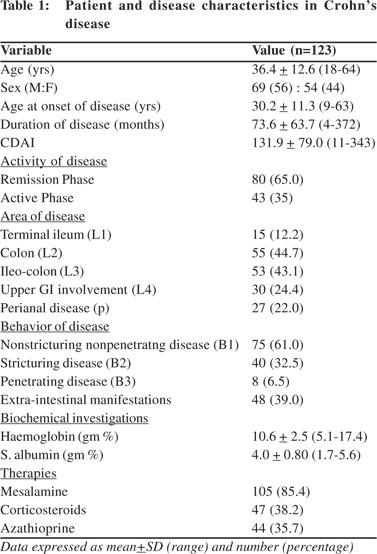

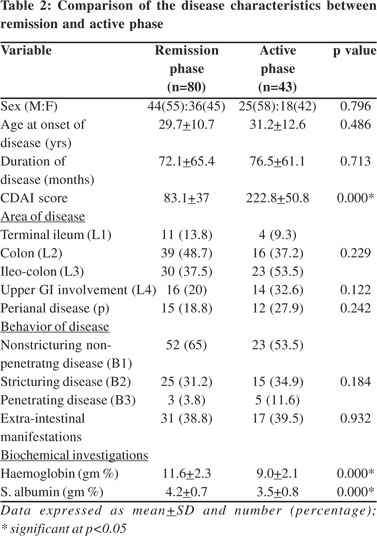

A total of 123 patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) and 100 age and sex matched healthy controls were enrolled in the study. There was no significant difference in the age of the patients and controls (patients vs. controls = 36.4+12.6 vs. 34.3+10.4 years; p=0.164). Gender distribution among patients and controls was also comparable (patients vs. healthy controls, M:F= 69(56%): 54(44%) vs. 60 (60%): 40 (40%); p=0.587. The patient and disease characteristics are shown in Table 1. There was no significant difference in disease characteristics like age at onset, duration of disease, area and behavior of disease between patients in remission and in active phase (Table 2).

However a significant difference was seen in the CDAI score, hemoglobin and albumin levels between both the groups. There was no significant difference in the age and gender distribution between patients in remission phase, active phase and healthy controls (remission vs. active vs. healthy controls; M:F = 44 (55%):36 (45%) vs. 25 (58%):18 (42%) vs. 60 (60%):40 (40%); p=0.796 and age+SD = 35.8+12 vs. 37.6+13.6 vs. 34.3+10.4; p= 0.275.

Body composition

Body composition

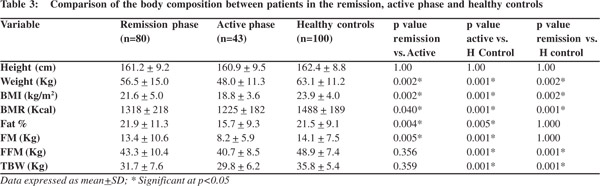

Table 3 depicts the components of body composition in remission and active phase as compared to controls. We found that weight, BMI and BMR of the patients in both remission and active phase were lower compared to that of healthy controls. The FM of the patients in active phase was lower than that of patients in remission phase as well as from that of healthy controls. However there was no significant difference in the FM of the patients in remission phase and healthy controls. On the contrary fat free mass (FFM) of patients in both active and remission phase was lower as compared to healthy controls, but there was no significant difference in the FFM of active and remission phase.

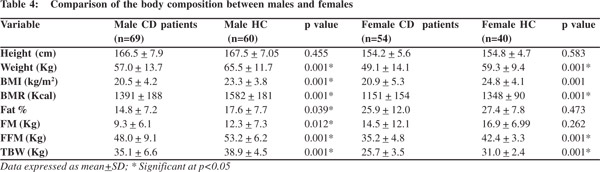

Gender specific analysis showed that both FM and FFM of the male patients were lower than healthy controls however in females only FFM was lower than healthy controls. There was no significant difference between the FM of female patients and female controls (Table 4).

Both FM and FFM showed a significantly inverse relationship with disease activity as assessed by CDAI (CDAI vs. FM, r=-0.342; p<0.000, CDAI vs. FFM, r=-0.251; p=0.005).

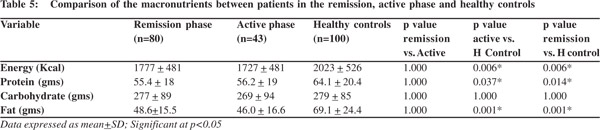

Intake of macronutrients

The intake of energy, protein and fat by patients in both remission and active phase was lower than that of healthy controls (Table 5). However no significant difference was seen in carbohydrate intake between the three groups. The intake of energy, protein, carbohydrates, and fats were comparable between remission and active phases of the disease.

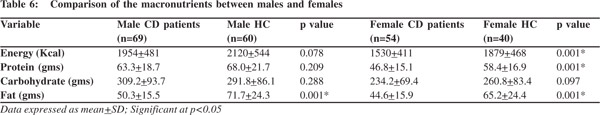

A gender specific analysis revealed that except for fat the intake of energy, protein and carbohydrate was comparable between male patients and healthy controls (Table 6). Male patients had a lower fat intake than healthy controls. In contra distinction the dietary intake of female patients was significantly lower in energy, protein and fat as compared to their healthy counterparts.

Discussion

In the present study we found that patients with Crohns disease are malnourished, have reduced weight and BMI in comparison to healthy individuals.When compared to matched controls, patients in active disease phase were found deficient in both fat mass (FM) and fat free mass (FFM), while those in remission phase were found to be deficient only in FFM with a preserved FM, the latter being comparable to that in healthy controls. Although many studies have reported alterations in both these components in CD patients, but their results remain equivocal.

Our findings are in line with that of Tjellesen et al

[9] who employed DEXA techniques in a small group of 30 CD patients in remission.They reported a significantly low FFM in patients as compared to healthy controls, however the absolute values of FM did not differ significantly between patients and healthy controls. Similarly Jahnsenet al

[10] also found that CD patients in remission phase had a significantly lower lean body mass (LBM) than healthy controls, but the FM was comparable between the groups. The findings of Geerling et al

[11]differed from above reports.They found no difference in the percent body fat of newly diagnosed CD patients in remission when compared with healthy controls. On the contrary these patients had a higher FFM compared to healthy controls. Such an observation could be because of a very small study cohort of only 20 patients and a relatively recent onset of disease in enrolled subjects. Using simple anthropometry, Rocha et al

[12]studied 50 patients with CD and found that muscle mass depletion was a common feature during both active and remission phases of CD. Fat mass depletion occurred sharply in the active phase and partially recovered during the remission phase, indicating a poor recovery of the muscle mass.Since they did not include a control population, a comparison with matched healthy individuals was not possible.

Notwithstanding the above reports, some studies have reported a preserved FFM, but a reduced FM in patients with CD. Capristo et al

[13]in 1998 conducted a study including both UC and CD patients in remission and found that patients with CD had lower FM compared to healthy controls, but no difference was seen in their FFM. It has been suggested that the decreased body weight frequently observed in IBD patients represents a predominant loss in body fat, sparing the FFM.

[14] More recently in 2006, Filippi et al15reported no difference between the nutritional status (weight and BMI) of 54 CD patients and 25 healthy controls, however they did find that the patients had a significantly lower body FM with a trend towards a higher FFM.These studies have supported the hypothesis of increased utilization of lipid as a fuel substrate resulting in a reduced FM and a preserved FFM.

[2,

16]

The characterization of body composition in patients with CD in terms of FM and FFM has always been a contentious issue, with conflicting reports suggesting a decreased FM, preserved FFM and vice versa.The pattern of lean mass deficit without fat mass deficit as seen in our CD patients in remission is termed as cachexia

[17] and may be attributed to a variety of factors.The muscle active cytokines may stimulate protein degradation and inhibit myogenic differentiation and induce myoblast apoptosis, thereby leading to poor lean mass.

[18]The corticosteroids administered to these patients may also have a negative effect on the muscle accrual as steroids are well known to enhance adiposity.

[19] An inadequate and often self restricted diet and reduced physical activity may also contribute to a reduced lean mass in these patients. Our patients had a significantly lower intake of macronutrients compared to controls.Though no difference was seen in the diet intake of patients in remission and active phase, it may be inadequate in view of their increased requirements. Hence the difference manifested in their body composition may partially be attributed to an inadequate dietary intake. Nonetheless, physiological stress and other above mentioned disease related factors per se may also have a substantial role in FFM reduction in these patients.

The main purpose of body composition estimation is to determine existing differences and set nutritional and therapeutic goals for patients accordingly. As evident from this study,even CD patients in remission phase need nutritional counseling and additional supplements to regain their lost FFM, and to counter balance the physiological stress and disease and therapy related adverse factors. In the present study a gender specific analysis revealed an interesting finding. Male patients with CD were deficient in both FM and FFM but females were deficient only in the FFM component with a preserved FM. Similar to our findings, Geerling et al

[20,

21] also reported a reduced FM only in male patients with CD. Guerreiro et al

[22] in 2007 studied the body composition in patients with CD with mild to moderate disease activity and found a significantly lower FM as well as FFM in males compared to controls, however in women only FFM was lower than controls. In contrast, Jahnsen et al

[10] found decreased FFM in both male and female patients, while FM was comparable in both genders with that of healthy controls.

Burnham et al

[18] in 2005 reported a somewhat similar finding in a large mixed group of children and young adults with CD (n=104), where a reduction in FFM was seen; however there was no deficit in the FM in both males and females.

When we looked at their diets we found that male diets were deficient only in fat compared to matched controls, but females had a lower intake of energy, protein, as well as fat. In spite of a grossly deficient diet, females did not have FM depletion. As there was an equal distribution of male and female patients in remission and active phases, this difference in gender cannot be attributed to disease activity per se. higher tendency towards fat accumulation in women, especially during post partum period and a common tendency for truncal fat deposition with poor lean mass in Asian women could explain a preserved FM in our female patients.To further put these differences in perspective, it is worth noting that there is a higher prevalence of abdominal obesity among Asians, including Indians, even when their BMI may be less than

[25.

23]

Our study comprising of relatively large cohorts of CD patients and healthy controls, showed that both FFM and FM are depleted in active disease phase,while only FM is preserved in the remission phase. This characterization of body composition not only suggests a predominant effect of disease and therapeutic factors but also an inadequate dietary intake among our patients. Hence, we suggest continuous nutritional supplementation and aggressive dietary counseling of these patients even in remission phase of their disease, in order to sustain a near normal body composition.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) for providing research grant to carry out this work.

References

- Fleming CR. Nutrition in patients with Crohn’s disease: anotherpiece of the puzzle. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr.1995;19:93–4.

- Capristo E. Body composition and metabolic features in Crohn’s disease: an update. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 1998;2:111–3.

- Burnham JM, Shults J, Semeao E, Foster BJ, Zemel BS, Stallings VA, et al. Body-composition alterations consistent with cachexia in children and young adults with Crohn disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:413–20.

- Royall D, Greenberg GR, Allard JP, Baker JP, Harrison JE, Jeejeebhoy KN. Critical assessment of body-composition measurements in malnourished subjects with Crohn’s disease: the role of bioelectric impedance analysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1994;59:325–30.

- Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F Jr. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:439–44.

- Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T,Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR,et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19:5–36.

- Eisenkolbl J, Kartasurya M, Widhalm K. Underestimation of percentage fat mass measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis compared to dual energy X-ray absorptiometry method in obese children. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2001;55:423–29.

- Gopalan C, Rama Sastri BV, Balasubramanian SC. Food composition tables.Nutritive value of Indian foods. 2nd ed. NIN, ICMR, Hyderabad .1989.p.47–58.

- Tjellesen L, Nielsen PK, Staun M. Body composition by dualenergy X-ray absorptiometry in patients with Crohn’s disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998;33:956–60.

- Jahnsen J, Falch JA, Mowinckel P, Aadland E. Body composition in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1556–62.

- Geerling BJ, Lichtenbelt WD, Stockbrügger RW, Brummer RJ. Gender specific alterations of body composition in patients with inflammatory bowel disease compared with controls. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1999;53:479–85.

- Rocha R, Santana GO, Almeida N, Lyra AC. Analysis of fat and muscle mass in patients with inflammatory bowel disease during remission and active phase. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:676-9.

- Capristo E, Mingrone G, Addolorato G, Greco AV, Gasbarrini G. Metabolic features of inflammatory bowel disease in a remission phase of the disease activity. J Intern Med. 1998;243:339–47.

- Royall D, Greenberg GR, Allard JP, Baker JP, Jeejeebhoy KN. Total enteral nutrition support improves body composition of patients with active Crohn’s disease. JPEN J Parent Enter Nutr. 1995;19:95–9.

- Filippi J, Al-Jaouni R, Wiroth JB, Hébuterne X, Schneider SM. Nutritional deficiencies in patients with Crohn’s disease in remission. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:185–91.

- Mingrone G, Greco AV, Benedetti G, Capristo E, Semeraro R, Zoli G,et al.Increased resting lipid oxidation in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:72–6.

- Rall LC, Roubenoff R. Rheumatoid cachexia: metabolic abnormalities, mechanisms and interventions.Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004;43:1219–23.

- Burnham JM, Shults J, Semeao E, Foster BJ, Zemel BS, Stallings VA, et al. Body-composition alterations consistent with cachexia in children and young adults with Crohn disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:413–20.

- Canalis E, Pereira RC, Delany AM. Effect of glucocorticoids on the skeleton. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2002;15:1341–45.

- Geerling BJ, Badart-Smook A, Stockbrügger RW, Brummer RJ. Comprehensive nutritional status in recently diagnosed patients with inflammatory bowel disease compared with population controls. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54:514–21.

- Geerling BJ, Badart-Smook A, Stockbrügger RW, Brummer RJ. Comprehensive nutritional status in patients with long-standing Crohn disease currently in remission. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998;67:919–26.

- Sousa Guerreiro C, Cravo M, Costa AR, Miranda A, Tavares L, Moura-Santos P, et al. A comprehensive approach to evaluate nutritional status in Crohn’s patients in the era of biologic therapy: a case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2551–6.

- Misra A, Vikram NK. Clinical and pathophysiological consequences of abdominal adipositiy and abdominal adipose tissue depots. Nutrition. 2003;19:457–66.