Chithra P,1 Chandrikha C,1 Arun Srinivasan Kannan,1 Srinath Sundararajan,1 Vijaya Srinivasan,2 Jayanthi V1

Department of Gastroenterology,1

Stanley Medical College Hospital,

Chennai

Department of Community Medicine,2

Vinayaka Missions Medical College, Salem,

India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. V Jayanthi

Email: drjayanthi35@yahoo.co.in

Abstract

Background: Several definitions and classifications have been designed to characterize functional dyspepsia (FD), the recent one being the ROME III criteria. There have been many studies in the western population which aimed at identifying the risk factors involved in functional dyspepsia. There are fewer studies from south Asian countries.

Aim: To determine the clinical and life style variables influencing functional dyspepsia and its sub-types in patients attending a tertiary care referral centre in the Indian subcontinent.

Methods: Consecutive patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms including, epigastric pain/burning, early satiety, postprandial fullness, heartburn and/or chest discomfort, alone or in combination, on more than 3 occasions a week, within the preceding 6 months and with a normal endoscopy were included in the study. Demographic details and the symptom profile including frequency of symptoms were recorded in a pre-structured, validated, modified proforma as per the ROME III criteria and analyzed to test the study hypothesis.

Results: Of the 170 patients, the median age of presentation was 49 yrs and the male to female ratio was 0.62 (65:105). The mean BMI was 23.8 kg/m2. Women had a higher BMI than men. More than half of the study subjects were from the low socio-economic groups.77.6% had ulcer type symptoms and showed a decreasing trend with age. It was more common in patients with higher per capita income. Reflux type comprised of 60.6% with predominance in women. 7% had early satiety and 13.5% had postprandial fullness. Nausea and belch as an isolated (associated) phenomenon comprised of 18.8% and 17.1% respectively. None of the lifestyle variables or demographic characteristics showed a significant influence on symptom occurrence.

Conclusions: There was a considerable overlap of various sub-types of dyspepsia. There were no differences in life style characteristics or significant risk factors in the various subtypes of dyspepsia.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|490 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Dyspepsia refers to a constellation of upper gastrointestinal symptoms that occur commonly in adults. It is one of the most common reasons for referral to any gastrointestinal unit. In the West up to 50% of subjects are on medication for symptomatic dyspepsia and 30% take leave of absence from work.[1]

Worldwide, the prevalence of uninvestigated dyspepsia varies between 7-45%, depending on the definition used and geographical location. The prevalence of functional dyspepsia (FD) has been noted to vary between 11-29.2%.[2] Population based estimates of functional dyspepsia in India are sparse. A study from Mumbai, India had shown that almost a third of the population suffered from dyspepsia (30.4%) with 12% experiencing significant symptoms.[3] While dyspepsia is known to result from organic causes, majority of patients suffer from non-ulcer or functional dyspepsia. Dyspepsia can thus be a manifestation of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) or peptic ulcer disease or functional dyspepsia (FD).

Based on findings at upper endoscopy, it has been estimated that the prevalence of FD is as high as 60%.[4,5] Several studies from the west have attempted to identify the determinants of FD.[4-6] For instance, environmental factors such as smoking, alcohol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are believed to be important in the pathogenesis of functional dyspepsia. Similar information is not available from the Indian subcontinent. There is a need to identify these risk factors. This would help to identify dyspepsia patients with high risk factors, so that detailed work-up and preventive measures can be instituted for them.

This study was undertaken at the gastroenterology unit of a tertiary care referral centre to categorise the sub-types of functional dyspepsia, identify any differences in life style variables or risk factors amongst hospital attendees with dyspepsia and their sub-types.

Methods

Consecutive patients attending our Department of Gastroenterology over a 3 month period, with symptoms of dyspepsia i.e. those with epigastric pain, post-prandial fullness/ bloating/ early satiety, belch phenomenon, nausea or vomiting, or presenting with heartburn or regurgitation and chest discomfort for more than 3 occasions a week, within the preceding 6 months were enrolled in this study. The ROME III modules (functional dyspepsia module; nausea, vomiting and belching disorders module, functional esophageal disorders module)[7] (Table 1) were modified as a questionnaire to further sub-type these patients under ulcer type, dysmotility type, reflux type and combination type based on the dominant symptom and its duration. For example if a patient had heartburn for 15 months and food relieving burning pain in the epigastrium for 6 months, the patient was classified as suffering from reflux type dyspepsia. If both the above symptoms appeared simultaneously, this was categorized as combination type dyspepsia. Nausea and belch phenomenon were coded either as individual symptoms or in combination with other types of dyspepsia. All patient details were compiled in a pre-structured and pre-tested questionnaire.

Our study variables included age, gender, marital status, religion, socio-economic details: occupation, literacy status, per capita income, and type of house (hut, temporary / permanent construction), household amenities; and details of smoking, alcoholism and three day diet recall.

All patients underwent an upper GI endoscopy and an ultrasound. Only patients with a normal endoscopy and ultrasound during the study period, and >15 years of age, belonging to either gender were included in the study. Patients with alarming symptoms such as anorexia, weight loss, gastrointestinal bleed, progressive dysphagia and mass abdomen were excluded from the study. Individuals with diabetes, hypothyroidism, chronic NSAID users, post-gastric surgery, gall stone disease and pregnancy were also excluded from the study.

For analysis, the mean duration of symptoms, life style variables including smoking, alcoholism and diet details were compared between the three sub-types of dyspepsia. The study was approved by our institutional ethics committee.

Our study variables included age, gender, marital status, religion, socio-economic details: occupation, literacy status, per capita income, and type of house (hut, temporary / permanent construction), household amenities; and details of smoking, alcoholism and three day diet recall.

All patients underwent an upper GI endoscopy and an ultrasound. Only patients with a normal endoscopy and ultrasound during the study period, and >15 years of age, belonging to either gender were included in the study. Patients with alarming symptoms such as anorexia, weight loss, gastrointestinal bleed, progressive dysphagia and mass abdomen were excluded from the study. Individuals with diabetes, hypothyroidism, chronic NSAID users, post-gastric surgery, gall stone disease and pregnancy were also excluded from the study.

For analysis, the mean duration of symptoms, life style variables including smoking, alcoholism and diet details were compared between the three sub-types of dyspepsia. The study was approved by our institutional ethics committee.

Statistical analysis

Test of proportions and Chi-square test were used for categorical variables while the Student t-test, and ANOVA were used for continuous numerical variables. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. SPSS (version 16) statistical package was used for data analysis.

Results

Population characteristics

A total of 170 out of 720 patients screened for this study fulfilled our criteria. There were 65 (38.2%) men. The overall median age was 49 years. Nearly three fourths (73%) were below the age of 60 years. The mean Body Mass Index (BMI) for the entire group of patients was 23.8±3.5 kg/m2. The BMI was significantly higher among women at 24.5 compared to that of men at 22.7 (ttest p <0.05). Based on religious preferences, Hindus constituted 80.7% and Christians 10.5% of the study population, while the rest were Muslims. This distribution is similar to that in the general population of Tamil Nadu, India.

Two thirds of the subjects (68%) were married, 11% were not married and 19% were widowed, majority of whom were women. More than a third of the population (37.7%) were housewives and a third (33.5%) were labourers or semi-skilled workers like fitters, mechanics, electricians or carpenters. A third of the population was illiterate, and 60% had either primary/secondary school education. Illiteracy was slightly higher amongst women (41%). The study subjects were from a low socioeconomic group. Nearly half (45%) lived in temporary houses and a third (31%) in huts. Other indices of socioeconomic data such as per capita income and amenities within the household did not reflect their actual economic status as housing did. Hence in this study, housing was taken as a proxy for socioeconomic status.

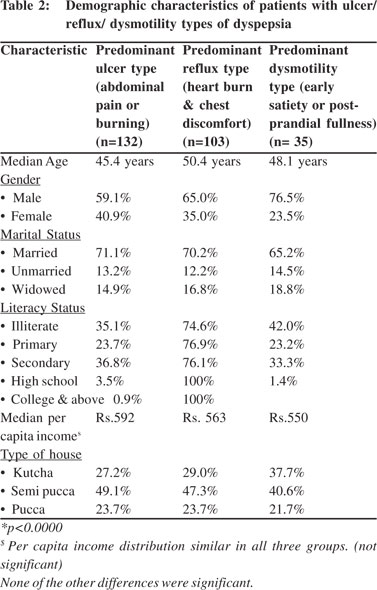

Table 2 summarises the demographic characteristics of 170 patients in the three subgroups viz. the ulcer type, reflux type and the dysmotility type. Majority of the patients [107 (60.3%)] had combination of symptoms. The dominant symptom with the longest duration was used to classify the patients into major sub-types.

Background characteristics of individual cases

Median age group of the three types of FD cases was similar at around 45 to 50 years. Similar proportion of males and females had ulcer type or reflux disease while dysmotility was significantly higher (p<0.01) among females (43.8% compared to 35.4%). There was no difference in any other socioeconomic characteristic such as marital status, literacy, median per capita income or type of income with respect to the three types of dyspepsia. The BMI of the patients was also similar among the three groups. The overall mean duration of symptoms was 1.95 ± 1.7 years.

Ulcer type dyspepsia

Of the 132 (77.6%) patients with ulcer type dyspepsia, 37 (28.0%) had only ulcer type symptoms; 58 (43.9%) and 4 (3.0%) patients had in addition reflux type and dysmotility symptoms respectively. The remaining 17 patients (12.9%) had combination of all three types of dyspepsia. In addition, 23 (17.4%) and 21 (15.9%) patients also had nausea and belch phenomenon. Thus ulcer type dyspepsia often presented with combination of other types of dyspepsia (95 patients). The mean (±SD) duration of symptoms was 2.08 ± 1.8 years.

Reflux type dyspepsia

Reflux type dyspepsia was present in 103 (60.6%) patients. 12.9% had associated chest pain. Apart from ulcer type combination (43.9%), 17 patients had coexisting (16.5%) dysmotility symptoms. In addition, almost a quarter had nausea and belch phenomenon (each 22.4%). The incidence of reflux symptoms as presenting complaints showed a steady increase up to the age of 60 years and then levelled out from there on (38%) .Women were symptomatic more often than men (34.2% vs. 27.6%). The mean duration of symptoms was 1.95 ± 1.7 years.

Dysmotility type dyspepsia

Dysmotility type of dyspepsia manifested as early satiety and post-prandial fullness in 12 (7.0%) and 23 (13.5%) patients respectively. There was no significant gender or age difference within the symptom groups. The mean duration of symptoms was 1.66 ± 1.3 years. Dyspeptic combinations with ulcer and reflux type of disease were distributed as mentioned above.

Miscellaneous

Of the 32 patients (18.8%) with nausea, 5 patients had symptom overlap with all three types of dyspepsia and only 3 had nausea alone. This symptom did not vary between different gender and age groups.

Belch phenomenon was seen in 29 patients (17.1%), and its combination with the three types of dyspepsia was not uncommon. Like nausea, this symptom did not show any variation across different gender and age groups. 13 (7.6%) patients reported experiencing a combination of nausea and belch phenomenon. The mean duration of nausea was 2.11 ± .2 years and for belch it was 1.35 ± 1.15 years.

Mean duration of dyspepsia

The coefficient of variation for the duration of symptoms in the different categories was very large indicating that their distribution was highly skewed. Thus the symptom free period being less than a year indicated the severity of disease in this population.

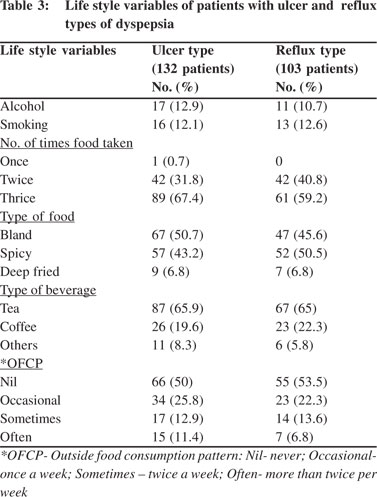

Lifestyle variables between the sub-types

In ulcer type dyspepsia, religion did not influence the occurrence of pain. This sub-type was significantly more common amongst those with higher per capita income and in those residing in permanent houses (80% vs. 60.4%). The number of patients in the dysmotility and miscellaneous group were too few for comparing lifestyle variables between these sub-groups. Table 3 summarizes the differences in lifestyle variables between ulcer and reflux types of dyspepsia. Rice was the staple food in almost all the patients and hence was not considered as an important variable for association with symptoms of functional dyspepsia. The interval between meals and type of oil did not influence the type of dyspepsia. None of the lifestyle variables demonstrated any significant influence on ulcer or reflux type of dyspepsia except for an increasing trend in ulcer type dyspepsia in patients who more frequently consumed food from commercial vendors (p <0.01).

Discussion

The predictors of non-ulcer dyspepsia are poorly defined. In the present study, a large degree of overlap was noted among different types of dyspepsia, heartburn and regurgitation. Similar observations have been made by others.[8-10] Ulcer with reflux type dyspepsia emerged as the most common combination in our study. In a recent presentation by Vakil et al[11], the authors reported a significant overlap between postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) and epigastric pain syndrome (EPS), in primary care patients with FD. In their study of 153 patients with FD, 111 (73%) had PDS and 100 (65%) had EPS and 75 (49%) had both class of symptoms. In contradistinction to above observations, the number of patients with dysmotility dyspepsia (PDS) in our series was significantly lower (20%) and was more often found in combination with either reflux or ulcer type dyspepsia (EPS). The most common overlapping syndrome in our study was the combination between ulcer type (EPS) and reflux type dyspepsia.

While ulcer type dyspepsia showed a decreasing trend with age among our patients, the reverse was seen with reflux type disease. The influence of lifestyle variables on dyspepsia is variable. We did not find any of the lifestyle variables like smoking, alcohol consumption or dietary patterns to influence the type of dyspepsia. These findings are similar to reports by Talley et al[12] and others who found no correlation between smoking, alcohol, NSAIDs and functional dyspepsia. In a community based study, Talley et al[6] found that dyspepsia was significantly more common in younger subjects and females. Adjusting their findings for age and gender, they found that smoking (OR=1.5), but not alcohol (OR=0.9), was associated with dyspepsia (p <0.05). Similar results were obtained when ulcer-like, dysmotility-like, and reflux-like dyspepsia was considered separately. The authors[6] concluded that smoking and alcohol may not be important risk factors for dyspepsia in the community.

Mahadeva et al[2] in a global review on risk factors for dyspepsia, reported that female gender and underlying psychological disturbances increased the risk for FD, while on the other hand environmental / lifestyle habits such as poor socio-economic status, smoking, increased caffeine intake and ingestion of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs appeared to be more relevant in cases of non-investigated dyspepsia.[1] Talley et al[12] studied the influence of smoking, alcohol, aspirin, non-aspirin NSAIDs, and acetaminophen in 73 patients with dyspepsia in comparison with 658 patients without dyspepsia. They found no association of these factors with FD. They noted that patients were significantly less likely to have FD if they were current or past smokers. Their data suggested a trend for patients to less likely to develop functional dyspepsia, if they took NSAIDs regularly. Further, they showed that environmental factors did not appear to be associated with any of the sub-types of dyspepsia.

Bode[13] in a study on 288 subjects with dyspepsia, aged 50- 85 yrs (mean 65 ± 7.2), found that female sex (OR=1.6; 95% CI=0.9-2.9) and current smoking (OR=3.7; 95% CI=0.9-15.4) were associated with a high symptom score. Patients above the age of 70 years were associated with a significantly lower symptom score (OR=0.4; 95% CI=0.2-0.9).[13] They however did not look into differences in risk factors between the various sub-types. In conclusion, similar to other reports from the West, demographic characteristics, social habits like smoking and alcohol failed to show any significant association with functional dyspepsia in our study.[10,14,15] Dietary factors hitherto unexplored by other workers also do not appear to influence the consequences and type of dyspepsia a patient develops.

References

- Haycox A, Einarson T, Eggleston A. The health economic impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the general population: results from the Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study (DIGEST). Scand J Gastoenterol Suppl. 1999;231:38–47.

- Mahadeva S, Goh KL. Epidemiology of functional dyspepsia: a global perspective. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2661–6.

- Shah SS, Bhatia SJ, Mistry FP. Epidemiology of dyspepsia in the general population in Mumbai. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2001;20:103–6.

- Bytzer P, Hansen JM, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB. Empirical H2-blocker therapy or prompt endoscopy in management of dyspepsia. Lancet. 1994;343:811–6.

- Heikkinen M, Pikkarainen P, Takala J, Rasanen H, Julkunen R. Etiology of dyspepsia: four hundred unselected consecutive patients in general practice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1995;30:519–23.

- Talley NJ, Zinmeister AR, Schleck CD, Melton LJ 3rd. Smoking, alcohol and analgesics in dyspepsia and among dyspepsia subgroups : lack of an association in a community. Gut. 1994;35:619–24.

- Thompson WG, Drossman DA, Talley NL, Walker L, Whitehead WE. In ROME III Diagnostic Questionnaires: Appendix C; Rome III Diagnostic Questionnaire for the Adult Functional GI Disorders (including Alarm Questions) and Scoring Algorithm 17–951((http://romecriteria.org/pdfs/DyspepMode.pdf))

- Haque M, Wyeth JW, Stace NH, Talley NJ, Green R. Prevalence, severity and associated features of gastro-oesophageal reflux and dyspepsia: a population based study. N Z Med J. 2000;113;178–81.

- Grainger SL, Klass HJ, Rake MO, Williams JG. Prevalence of dyspepsia: the epidemiology of overlapping symptoms. Postgrad Med J. 1994;70:154–61.

- Shaib Y, El-Serag HB. The prevalence and risk factors of functional dyspepsia in a multiethnic population in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2210–6.

- Vakil NB, Halling K, Wernersson B, Ohisson L. ROME III Functional Dyspepsia (FD) criteria : Poor discrimination between postprandial distress symdrome, DDW, Chicago, 2011(presentation No: 103).

- Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR. Smoking, alcohol, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in outpatients with functional dyspepsia and among dyspepsia subgroups. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994;89:524–28.

- Bode G, Brenner H, Adler G, Rothenbacher D. Dyspeptic symptoms in middle-aged to old adults: the role of Helicobacter pylori infection, and various demographic and lifestyle factors. J Intern Med. 2002;252:41–7.

- Saito YA, Locke G 3rd, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. Diet and functional gastrointestinal disorders: a population-based case–control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2743–8.

- Tougas G, Chen Y, Hwang P, Liu MM, Egglest on A. Prevalence and impact of upper gastrointestinal symptoms in the Canadian population: findings from the DIGEST study. Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:2845–54.

|