Ambika P Dash1, Tapas Mishra1, Manoranjan Mohapatra2, MD. Ibrarullah1

Dept of Surgical Gastroenterology

Hitech Medical College and Hospital;1

Department of Radiology, Kalinga Hospital,2

Bhubaneswar – 751010, Orissa, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Md. Ibrarullah

Email: m_ibrarullah@yahoo.co.in

drambika.dash@gmail.com

48uep6bbphidvals|522 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Spontaneous common bile duct (CBD) perforation in adults is a rare clinical event. Acute onset and delay in diagnosis can lead to considerable morbidity. We report here two successfully managed cases of spontaneous CBD perforation. Both presented as acute abdomen with localized bilioma. The diagnosis and management of these patients have been discussed.

Case 1

A 28-year-old-female, diagnosed case of choledocholithiasis, presented with progressively increasing jaundice and acute pain upper abdomen. At laparotomy carried out elsewhere, the surgeon noticed a mass in the subhepatic region extending along the right paracolic gutter to the lumbar area. The gall bladder and common bile duct (CBD) were inaccessible. Hence the surgeon decided to close the abdomen and refer the patient to our centre. On examination, a tender mass was palpable in the right abdomen extending from the right hypochondrium to right lumbar region. Computed tomography(CT) of abdomen showed a fluid collection extending from the bile duct region to the right paracolic gutter (Figure 1). Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) revealed a CBD stone and a large fluid collection communicating with the CBD at its junction with the cystic duct (Figure 2). A diagnosis of spontaneous CBD perforation and bilioma was made. An ultrasound (US) guided percutaneous catheter was placed that drained approx 500 ml of bile initially and 200-300ml bile on subsequent days. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiogram (ERC) was carried out to confirm and manage the leak but failed because the impacted stone did not allow the dye to delineate the proximal duct. Laparotomy performed 6 weeks later revealed dense subhepatic adhesions, a contracted gallbladder and a dilated CBD with an impacted stone approximately one cm in diameter. A healed perforation could be demonstrated at the junction of cystic duct and CBD. Cholecystectomy, choledocholithotomy and T-tube drainage was performed after which the patient made an uneventful recovery. She is well after two years of regular follow-up.

Case 2

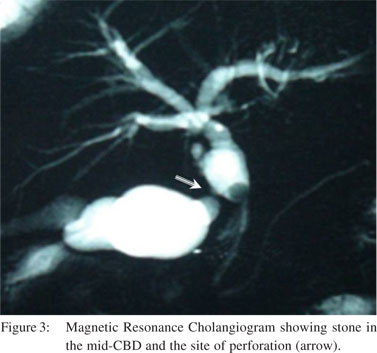

A 64-year-old-male presented with acute pain abdomen. He had developed jaundice for the last 10 days. On examination the abdomen was tender and rigid on the right side. An ill defined mass was palpable in the right hypochondrium. Ultrasound (USG) abdomen revealed a contracted gall bladder containing stones, a dilated CBD with a large stone distally and fluid collection in the right subhepatic and lumbar areas. A pig-tail catheter inserted under USG guidance drained around 500 ml of bile. MRCP performed three days later suggested bile leak from the CBD at the site of the stone (Figure 3). This finding was subsequently confirmed by ERC. A 10Fr, 10cm size plastic stent was placed in the CBD beyond the stone and the site of the leak. The bile leak stopped in 10 days. Two months later the patient was subjected to cholecystectomy, CBD exploration, stone extraction and T-tube drainage. The patient made an uneventful recovery. The T-tube was removed on the 21st day. After a regular follow-up of 18 months the patient is healthy and asymptomatic.

Case 2

A 64-year-old-male presented with acute pain abdomen. He had developed jaundice for the last 10 days. On examination the abdomen was tender and rigid on the right side. An ill defined mass was palpable in the right hypochondrium. Ultrasound (USG) abdomen revealed a contracted gall bladder containing stones, a dilated CBD with a large stone distally and fluid collection in the right subhepatic and lumbar areas. A pig-tail catheter inserted under USG guidance drained around 500 ml of bile. MRCP performed three days later suggested bile leak from the CBD at the site of the stone (Figure 3). This finding was subsequently confirmed by ERC. A 10Fr, 10cm size plastic stent was placed in the CBD beyond the stone and the site of the leak. The bile leak stopped in 10 days. Two months later the patient was subjected to cholecystectomy, CBD exploration, stone extraction and T-tube drainage. The patient made an uneventful recovery. The T-tube was removed on the 21st day. After a regular follow-up of 18 months the patient is healthy and asymptomatic.

Discussion

Spontaneous perforation of the bile duct is a rare clinical event. In infants rupture of choledochalcysts and anomalous union of pancreaticobiliary ductal system (AUPBD)are the commonest etiologies.[1]In adults only 90 cases have been reported so far.[2-4] Though termed spontaneous, most of the cases are associated with choledocholithiasis.[5] Other causes which may occasionally give rise to such events include choledochal cyst,[6] site of previous CBD exploration,[7] choledochoenterostomies,[3] pregnancy,[5] and acalculous cholecystitis.[8] The commonest site of bile duct perforation is at the junction of cystic and common hepatic duct, as was noted in the first case presented here. Developmentally this is a vulnerable site and hence predisposed to perforation consequent to obstruction due to any cause.[9]The large impacted stone distally was the cause of rise in intraductal pressure in the first patient. Pressure necrosis due to the impacted stone was the likely cause of perforation in the second patient.

Bile duct perforation presents as either a localized collection or as generalized biliary peritonitis.[10] Ultrasound is the first modality of investigation. Presence of biliary obstruction and a bilious aspirate from the fluid collection may point to a diagnosis of spontaneous perforation.[11-13] Other modalities used to diagnose this condition are biliary scintigraphy and intraoperative cholangiography.[10,11] Magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) has not been utilized as an investigation modality in any of the cases reported so far. Both our cases could be accurately diagnosed on MRC. ERC failed in the first patient due to the impacted stone. In suitable cases ERC not only helps confirm the diagnosis but also assists in management of the condition. The bile leak in the second patient could be diagnosed using ERC and placement of stent across the obstruction helped in tiding over the critical stage.

Single stage surgery in the form of drainage of bile collection and CBD exploration has been reported.[10]This strategy holds good for unsuspected perforations. In diagnosed cases, staged management helps in converting emergency into an elective situation. In both our patients, USG guided percutaneous catheter drainage of the bile collection and endoscopic drainage of the bile duct in the second patient helped in improving patients’ condition. This was followed by definitive elective surgery on a later date with a good final outcome.

References

Discussion

Spontaneous perforation of the bile duct is a rare clinical event. In infants rupture of choledochalcysts and anomalous union of pancreaticobiliary ductal system (AUPBD)are the commonest etiologies.[1]In adults only 90 cases have been reported so far.[2-4] Though termed spontaneous, most of the cases are associated with choledocholithiasis.[5] Other causes which may occasionally give rise to such events include choledochal cyst,[6] site of previous CBD exploration,[7] choledochoenterostomies,[3] pregnancy,[5] and acalculous cholecystitis.[8] The commonest site of bile duct perforation is at the junction of cystic and common hepatic duct, as was noted in the first case presented here. Developmentally this is a vulnerable site and hence predisposed to perforation consequent to obstruction due to any cause.[9]The large impacted stone distally was the cause of rise in intraductal pressure in the first patient. Pressure necrosis due to the impacted stone was the likely cause of perforation in the second patient.

Bile duct perforation presents as either a localized collection or as generalized biliary peritonitis.[10] Ultrasound is the first modality of investigation. Presence of biliary obstruction and a bilious aspirate from the fluid collection may point to a diagnosis of spontaneous perforation.[11-13] Other modalities used to diagnose this condition are biliary scintigraphy and intraoperative cholangiography.[10,11] Magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) has not been utilized as an investigation modality in any of the cases reported so far. Both our cases could be accurately diagnosed on MRC. ERC failed in the first patient due to the impacted stone. In suitable cases ERC not only helps confirm the diagnosis but also assists in management of the condition. The bile leak in the second patient could be diagnosed using ERC and placement of stent across the obstruction helped in tiding over the critical stage.

Single stage surgery in the form of drainage of bile collection and CBD exploration has been reported.[10]This strategy holds good for unsuspected perforations. In diagnosed cases, staged management helps in converting emergency into an elective situation. In both our patients, USG guided percutaneous catheter drainage of the bile collection and endoscopic drainage of the bile duct in the second patient helped in improving patients’ condition. This was followed by definitive elective surgery on a later date with a good final outcome.

References

- Chardot C, Iskandarani F, De Dreuzy O, Duquesne B, Pariente D, Bernard O, et al. Spontaneous perforation of biliary tract in infancy: a series of 11 cases. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1996;6:341–6.

- Lochan R, Joypaul BV.Bile peritonitis due to intra hepatic bile duct rupture. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6728–9.

- Kang SB, Han SB, Min SK, Lee HK. Nontraumatic perforation of bile duct in adults. Arch Surg. 2004;139:1083–7.

- Lee HK, Han HS, Lee JH, Min SK. Nontraumatic perforation of bile duct treated with laparoscopic surgery. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2005;15:329–32.

- Piotrowski II, Van Steigmann G, Liechty RD. Spontaneous bile duct rupture in pregnancy. HPB Surg. 1990;2:205–9.

- Jacson BT, Saunders P. Perforated choledochal cyst. Br J Surg.1971;58:38–42.

- Spira IA. Spontaneous rupture of the CBD. Ann Surg. 1976;183:433–5.

- Coe NP, Page DW. Spontaneous perforation of the common hepatic duct in association with acalculouscholecystitis. South Med J. 1981;74:893–6.

- Telang PS, Palep JH, Joshi RM. Spontaneous perforation of common bile duct in an adult. Bombay Hospital Journal. 2009;51:514–5.

- Patterson G. Spontaneous perforation of common bile duct in infants. Acta Chir Scand. 1955;60:192–201.

- Marwah S, Sen J, Goyal A, Marwah N, Sharma JP. Spontaneous perforation of common bile duct in an adult. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:58–9.

- Haller JO, Condon VR, Berdon WE, Oh KS, Price AP, Bowen A, et al.Spontaneous perforation of common bile duct in children. Radiology. 1989;172:621–4.

- Sai Prasad TR, Chui CH, Low Y, Chong CL, Jacobsen AS. Bile duct perforation in children: is it truly spontaneous? Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35:905–8.

|