Manisha Jana, Shivanand Gamanagatti

Department of Radiodiagnosis,

All India Institute of Medical Sciences,

New Delhi, India

Corresponding Author:

Dr. Shivanand Gamanagatti

Email: shiv223@rediffmail.com

Abstract

Transjugular liver biopsy (TJLB) is an important and relatively safer alternative to the traditional method of percutaneous liver biopsy, especially in patients with gross ascites or deranged bleeding parameters. In this article, we will highlight the instrumentation required for performing the procedure, the technical aspects of the procedure, the common complications encountered, and the troubleshooting methods to overcome the problems encountered during the procedure.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|528 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Liver biopsy is an essential constituent in the management of parenchymal liver disease and the percutaneous approach comprises the usual procedure of obtaining samples. Percutaneous liver biopsy is a commonly performed safe procedure, usually done in an outpatient setting. However, in certain clinical scenarios as with deranged coagulation and significant ascites, this simple procedure can pose significant risk to the patient. Transjugular liver biopsy (TJLB) is an alternative sampling procedure in which liver tissue samples are obtained through a transvenous route via the jugular vein, the vena cava and the hepatic veins.[1] As this procedure does not involve any breach of the hepatic capsule, the risk of hemoperitoneum is substantially reduced. In this article, we will describe the common indications, contraindications, the technique, success rate and procedure-related complications of transjugular liver biopsy.

Indications

The common and absolute indications for performing a transjugular liver biopsy include: i) deranged coagulation parameters (increased PT or PTT or reduced platelet count);[2-4] ii) massive ascites;[2-4] and iii) vascular hepatic tumors or peliosis hepatis. Other relative indications include technical difficulties owing to morbid obesity or a shrunken liver and a difficulty in obtaining samples using the percutaneous approach.

Contraindications

The contraindications to this procedure include:[5] i) gross dilation of the intrahepatic biliary radicles due to biliary obstruction, which may pose a risk of hemobilia after biopsy; ii) a hydatid cyst which can be accidentally punctured during a transvenous biopsy and give rise to anaphylactic reaction; iii) right internal jugular vein thrombosis poses a greater technical challenge to the operator, in terms of gaining useful access to the hepatic vein via the left jugular vein approach6 and can be a cause of procedural failure.

Instrumentation

Essential instruments and paraphernalia required for carrying out a transjugular liver biopsy includes: i) a TJLB needle with a stiff cannula (Figure 1); ii) a long sheath (7 Fr) (Figure 1); iii) a 0.035" terumo guidewire; iv) an Amplatz superstiff metallic guidewire; v) a 5 Fr multipurpose catheter; and vi) an 18 G intravenous cannula.

Procedure

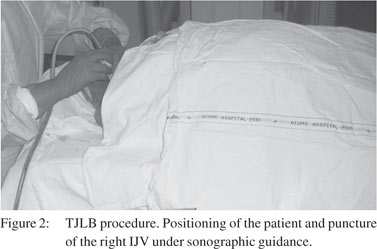

The procedure is usually performed under local anesthesia because it requires patient cooperation (breath holding). After obtaining proper informed consent, the patient should be placed in supine position. The right internal jugular vein (IJV) is best suited for procedural access, however, in the presence of right IJV thrombosis, the left IJV can be accessed though the latter requires greater operator experience. The neck should be rotated to the left for a right sided IJV puncture. The procedure should be commenced with proper aseptic precautions and surgical draping. The right IJV is punctured using an 18G cannula (single puncture) under real-time ultrasound guidance (Figure 2). The position of the needle tip should be checked by aspirating venous blood. While entering the IJV, all precautions should be taken to avoid air embolism. Hence the needle should be attached to a syringe filled with normal saline while aspirating. Inadvertent puncture of the carotid artery should be avoided. After confirming the needle position, a hydrophilic guidewire is introduced into the vein and using the Seldinger technique, a 6 Fr arterial sheath is inserted.

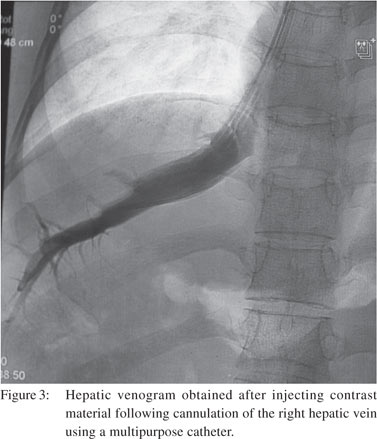

Under fluoroscopic guidance, a guidewire and a 5 Fr multipurpose catheter is passed into the superior vena cava (SVC), and navigated through the right atrium, the inferior vena cava (IVC) and finally into the right hepatic vein (RHV). One should be cautious about cardiac arrhythmias while crossing the right atrium. If the RHV cannot be cannulated, the middle hepatic vein (MHV) can also be cannulated. Once the hepatic vein is cannulated, a small amount of contrast is injected and a venogram is obtained (Figure 3). Obtaining a hepatic venogram is essential for ensuring proper placement of the catheter and the TJLB needle in subsequent steps. Once the position of the catheter is confirmed, a stiff guidewire is passed through it and a long (49 cm) 7 Fr sheath is inserted along with a stiff TJLB cannula over the stiff guidewire. If there is difficulty in cannulating the hepatic veins, gentle rotation of the catheter tip or attempts at deep inspiration might prove useful.

Under fluoroscopic guidance, a guidewire and a 5 Fr multipurpose catheter is passed into the superior vena cava (SVC), and navigated through the right atrium, the inferior vena cava (IVC) and finally into the right hepatic vein (RHV). One should be cautious about cardiac arrhythmias while crossing the right atrium. If the RHV cannot be cannulated, the middle hepatic vein (MHV) can also be cannulated. Once the hepatic vein is cannulated, a small amount of contrast is injected and a venogram is obtained (Figure 3). Obtaining a hepatic venogram is essential for ensuring proper placement of the catheter and the TJLB needle in subsequent steps. Once the position of the catheter is confirmed, a stiff guidewire is passed through it and a long (49 cm) 7 Fr sheath is inserted along with a stiff TJLB cannula over the stiff guidewire. If there is difficulty in cannulating the hepatic veins, gentle rotation of the catheter tip or attempts at deep inspiration might prove useful.

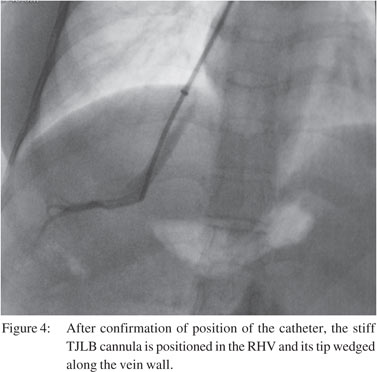

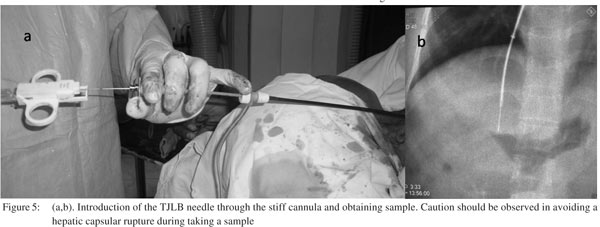

The metallic cannula of the TJLB needle should be wedged along the wall of hepatic vein against the hepatic parenchyma (Figure 4). The ideal position to take samples is along the midpart of a hepatic vein. While performing a biopsy through the RHV, the needle should be anteriorly directed, while it should be positioned laterally when performing the biopsy via the MHV. The rationale behind these precautions is to avoid breaching the hepatic capsule.[7] Once the assembly is wedged, the TJLB needle is prepared for sampling (by pulling the plunger back outside the body) and inserted (Figure 5) inside the metallic cannula so that the tip just projects beyond the cannula.[8] The patient is asked to hold his/her breath and the biopsy needle is fired. Once the sample is taken, the needle is withdrawn into the cannula and taken out for retrieval of the sample core. After completion of the procedure, a venogram should be performed (Figure 6) to rule out any active contrast leak into the peritoneal cavity. The long sheath and TJLB assembly is taken out and the local site compressed for proper haemostasis.

Troubleshooting

IJV puncture

It is recommended that ultrasound guidance is used and the IJV is punctured in the transverse plane rather than in the longitudinal plane to avoid carotid puncture. Use saline filled syringe attached to the needle to prevent air embolism. For problems in negotiating into the IVC, it is recommended that a multipurpose catheter is used with a straight tip terumo guide wire (rather than J tip) combination.

Problem in negotiating the right hepatic vein

While attempting entry into a particularly difficult RHV, it is recommended that different types of guide wires, with a J tip or a straight tip with multipurpose catheter combinations be employed. Use of different shaped catheters like the cobra catheter may also be attempted. The operator should attempt to pass the wire in different phases of respiration (e.g. deep inspiration). Further it helps to change the angle of the catheter posterolaterally while navigating from the right atrium to the IVC. If all attempts at cannulating the RHV fail, then its recommended that an MHV cannulation be attempted.

Problems in negotiating the stiffening cannula

In situations where the operator finds negotiating the stiffening cannula a challenge, it is recommended to try and negotiate the cannula over the extra support of the metallic guide wire. Attempts to pass the stiffener during deep inspiration also assist in negotiating passage. Slightly rotate and direct the cannula posterolaterally to the right side at the hepatic venous confluence, since the RHV at times may not be in a true coronal plane. It also helps to change the curve of the cannula outside the body of patient, to match the curvature of the RHV at the IVC-RHV junction.

Avoiding capsular breach

It is advisable to take the biopsy with patient holding his/her breath in inspiration. It is also important to avoid taking a biopsy from the peripheral one-third of the hepatic vein to avoid breach of the liver capsule. Direct the cannula anteriorly, since the liver tissue is more anteriorly. If the capsule is breached, always perform a check venogram which confirms the injury by contrast leakage into the peritoneal cavity. In case a breach is noted, embolise the breached tract using gel foam. If not sealed with gel foam, embolising the tract using glue is equally helpful.

Adequacy of sample

Three passes of samples are adequate. With a cirrhotic liver, fragmented samples are common. To acquire good sample size, it is imperative to wedge the cannula properly against the wall of the hepatic vein.

Complications

TJLB is a relatively safe procedure. Reported complication rate in different series varies from 0.5 to 1% and as high as 15%.[5] Minor complications include local pain, hematoma, paresthesia and transient cardiac arrhythmias during catheter manipulation Other puncture-related complications include pneumothorax and inadvertent carotid puncture, which can be avoided by judicious use of ultrasound guidance.

Major complications include hemoperitoneum due to rupture of the liver capsule either owing to technical reasons or a very small shrunken liver. Risk of significant intraperitoneal bleed is low to the tune of 0.2 to 0.5%.[9] Cholangitis and perforation of the hepatic capsule are other unusual complications. Fatal arrhythmias are rare. Mortality associated with this procedure is low (0.2-0.3%).[10] In case of significant hemoperitoneum, a post-procedure hepatic venogram can identify the source of bleed and the tract can be embolized. If the bleeding is from a branch of the hepatic artery, selective hepatic angiogram and embolization is warranted. If the source of bleeding cannot be identified, empirical embolization of the RHV branches can be performed.

Radiation dose

The procedure time is dependent on the expertise of the radiologist. The average fluoroscopy time has been reported to be less than 10 minutes and the dose varies from 0.5 - 1 mSv.[11]

Technical success rate

Technical success rate of TJLB is high, with failure rates from different studies approximating 3.2%.[12] The success rate depends on the experience of the radiologist. Most common cause of failure is inability to cannulate the RHV. Failure to cannulate the IJV is another common cause of procedural failure; and the chances increase if ultrasound guidance is not used for the jugular puncture. At times the procedure may have to be abandoned because of major intra-procedure complications like cardiac arrhythmias and severe hypotension.

Efficacy

Some studies have noted that inferior quality of samples are Transjugular liver biopsy 171

obtained by TJLB via an aspiration needle as compared to those obtained by a percutaneous biopsy.[13] However, a biopsy sample obtained using a tru-cut biopsy needle is often adequate to make a diagnosis (contains at least 6 to 8 portal tracts) of chronic liver disease,[14] with a diagnostic rate varying from 61 to 100% in some studies.[15]

Conclusion

Transjugular liver biopsy is an effective and safe technique and offers an important investigation tool for the management of parenchymal liver disease. When performed in experienced hands using a tru-cut biopsy gun, there is less risk of major complications with adequate sample acquisition.

References

- Weiner M, Hanafee WN. A review of transjugular cholangiography. Radiol Clin North Am. 1970;8:53–68.

- Bravo AA, Sheth SG, Chopra S. Liver biopsy. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:495–500.

- Lebrec D. Various approaches to obtaining liver tissue—choosing the biopsy technique. J Hepatol. 1996;25:20–4.

- McGill DB, Rakela J, Zinsmeister AR, Ott BJ. A 21-year experience with major hemorrhage after percutaneous liver biopsy. Gastroenterology. 1990;99:1396–400.

- Garcia-Compean D, Cortes C. Transjugular liver biopsy. An update. Ann Hepatol. 2004;3:100–3.

- Yavuz K, Geyik S, Barton RE, Petersen B, Lakin P, Keller FS, et al. Transjugular liver biopsy via the left internal jugular vein. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2007;18:237–41.

- Gamble P, Colapinto RF, Stronell RD, Colman JC, Blendis L. Transjugular liver biopsy: a review of 461 biopsies. Radiology. 1985;157:589–93.

- Keshava SN, Mammen T, Surendrababu N, Moses V. Transjugular liver biopsy: What to do and what not to do. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2008;18:245–8.

- McAffe JH, Keeffe EB, Lee RG, Rosch J. Transjugular liver biopsy. Hepatology. 1992;15:726–32.

- Bass NM, Yao FY. Transjugular procedures. Gastrointes Endosc Clin North Am. 2001;11:131–61.

- Mammen T, Keshava SN, Eapen CE, Raghuram L, Moses V, Gopi K, et al. Transjugular liver biopsy: a retrospective analysis of 601 cases. J Vasc interv Radiol. 2008;19:351–8.

- Kalambokis G, manousou P, Vibhakorn S, Marelli L, Cholongitas E, senzolo M, et al. Transjugular liver biopsy—indications, adequacy, quality of specimens, and complications—a systematic review. J Hepatol. 2007;47:284–94.

- Sada PN, Ramakrishna B, Thomas CP, Govil S, Koshi T, Chandy G. Transjugular liver biopsy: a comparison of aspiration and trucut techniques. Liver. 1997;17:257–9.

- Bravo AA, Seth SG, Chopra S. Liver biopsy. N Eng J Med. 2001;344:495–500.

- Miraglia R, Luca A, Gruttadauria S, Minervini MI, Vizzini G, Arcadipane A, et al. Contribution of transjugular liver biopsy in patients with the clinical presentation of acute liver failure. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2006;29:1008–10.

|