Mayank Jayant, Robin Kaushik

Department of Surgery,

Government Medical College and Hospital

Sector 32, Chandigarh, India.

Corresponding Author:

Dr Robin Kaushik

Email:robinkaushik@yahoo.com

Abstract

Background: Partial cholecystectomy is usually performed with the aim of preventing bile duct injury and/or vascular injuries in situations where there is difficulty in performing cholecystectomy. Occasionally, such patients can become symptomatic due to recurrence or persistence of disease in the gallbladder remnant and may require further treatment. Patients and methods: A case series of various presentations and follow up of seven patients who had undergone open partial cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstone disease in the past.

Results: Of 7 patients,6 were symptomatic , and each of them was found to have a remnant of the gallbladder (with calculi in the remnant in 4 patients). Three patients who presented with recurrent biliary symptoms were re-operated and the gallbladder remnant was removed, with resolution of the symptoms. Two patients refused further operation—one patient with acute pancreatitis who underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for removal of common bile duct stones, and another who presented with acute cholecystitis. The other 2 patients (one with transient jaundice and the other who is asymptomatic) remain on follow-up.

Conclusions: Although partial cholecystectomy is an accepted, safe option in difficult cases, these patients must be counselled regarding the recurrence of symptoms, and must be kept on follow-up. If symptoms develop, completion of cholecystectomy to remove the remnant provides symptomatic relief.

|

48uep6bbphidvals|591 48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext Cholecystectomy, either laparoscopically or by the conventional ‘open’ method, is considered to be the “gold standard” operation for gallstones, which provides relief of symptoms in a large majority of cases. However, at times, patients continue to experience upper gastrointestinal symptoms even after cholecystectomy, the so-called “postcholecystectomy syndrome”, which, at times, can be distressing and difficult to treat. Although a wide range of biliary as well as extra-biliary disorders can cause the “postcholecystectomy syndrome”, biliary strictures, retained stones in the common bile duct, or stones in a long cystic duct or in a remnant of the gallbladder are important treatable causes that must not be ignored in patients having persistent symptoms after cholecystectomy.[1]

A gallbladder remnant is sometimes left behind at the time of the initial operation, usually where partial cholecystectomy has been performed in difficult Calot’s triangle, where the anatomy may be distorted by recurrent episodes of inflammation, adhesions or bleeding. In such a situation, persisting with dissection in the Calot’s triangle can lead to major complications such as common bile duct and/or vascular injury, which can turn the procedure into a nightmare, both for the surgeon as well as the patient. In such cases, it is advisable to leave a cuff of the gallbladder near the Hartmann’s pouch, removing the rest of the gallbladder, in the manner described by Lerner[2] or Bornman and Terblanche[3] after removing all stones from the remaining cuff of the gallbladder. In recent times, further types of subtotal cholecystectomy have been described wherein the gallbladder was opened at the infundibulum, as close to the junction of the gallbladder and cystic duct as is safely possible, and the gallbladder flaps sutured after destroying the mucosa.[4,5] In these cases, there is always a stump of the gallbladder left behind that can cause problems, especially if care has not been taken to destroy the mucosa and remove any calculi prior to its closure. It should also be kept in mind, especially in patients who have undergone laparoscopic cholecystectomy that a long cystic duct is normally left behind, since safety lies in staying away from the common bile duct and applying clips close to the gallbladder– cystic duct junction. This is an inherent part of the operation that assumes importance if the patient becomes symptomatic later.

We present a short series of patients who presented to us with a variable presentation of gallbladder remnants.

Materials and Methods

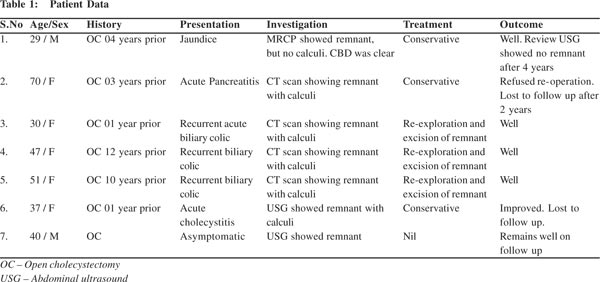

The records of 7 patients who presented to us with gallbladder remnant after having undergone cholecystectomy were reviewed and analysed with respect to the time period between initial cholecystectomy and presentation, symptomatology, clinical features, findings on investigation and further management. The details of these patients are given in Table 1.

Results

Seven patients (5 women and 2 men) were seen by us with gallbladder remnants, with an average age of 43.4 years (age range 29–70 years). Their clinical presentations were similar to that of gallstone disease, with the majority being middle-aged women. All the 7 patients had undergone elective partial cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstone disease—6 had undergone open cholecystectomy elsewhere, whereas 1 had been operated in our hospital, about 4 years ago.

Results

Seven patients (5 women and 2 men) were seen by us with gallbladder remnants, with an average age of 43.4 years (age range 29–70 years). Their clinical presentations were similar to that of gallstone disease, with the majority being middle-aged women. All the 7 patients had undergone elective partial cholecystectomy for symptomatic gallstone disease—6 had undergone open cholecystectomy elsewhere, whereas 1 had been operated in our hospital, about 4 years ago.

The common presentation was with recurrent attacks of upper abdominal pain (in 3 patients), with acute cholecystitis and pancreatitis (in 1 patient each). One patient presented with transient jaundice after about 2 years of partial cholecystectomy. Ultrasound done at that time (Figure 1) revealed a gallbladder remnant with sludge. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) done a few days later showed a gallbladder remnant without any stones or sludge, and the common bile duct was also clear. Since his jaundice (as well as liver functions) normalized without any intervention, nothing further was done, and he was kept on follow-up. A recent ultrasound done in December 2012 showed no residual gallbladder, and the possibility of fibrosis of the remnant was entertained after a repeat sonogram that was done to confirm the findings, which also showed the same results.

The common presentation was with recurrent attacks of upper abdominal pain (in 3 patients), with acute cholecystitis and pancreatitis (in 1 patient each). One patient presented with transient jaundice after about 2 years of partial cholecystectomy. Ultrasound done at that time (Figure 1) revealed a gallbladder remnant with sludge. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) done a few days later showed a gallbladder remnant without any stones or sludge, and the common bile duct was also clear. Since his jaundice (as well as liver functions) normalized without any intervention, nothing further was done, and he was kept on follow-up. A recent ultrasound done in December 2012 showed no residual gallbladder, and the possibility of fibrosis of the remnant was entertained after a repeat sonogram that was done to confirm the findings, which also showed the same results.

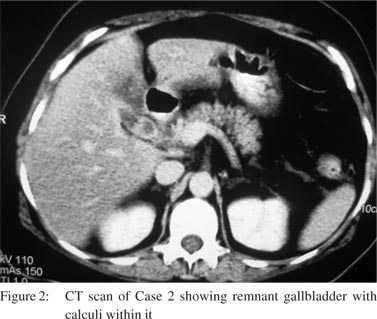

One patient was referred to us with abdominal sonogram done elsewhere that showed remnant of the gallbladder. However, since he was asymptomatic, he has been kept on a regular follow-up, and no intervention has been planned at present. One patient presented with pancreatitis (Figure 2) underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for clearance of the common bile duct. The patient refused the option of re-operation to remove the gallbladder remnant and was lost to follow-up after one year. Another patient who was admitted with acute cholecystitis did not come for follow-up after her symptoms resolved. Three patients were operated with the intention of performing “re-cholecystectomy” to remove the gallbladder remnant.

Although abdominal sonogram was the preferred initial investigation, computed tomography (CT) was performed for the assessment of pancreatitis in 1 patient, and in all the 3 patients who were planned for surgery, to give a better visual idea of the size and position of the gallbladder remnant, presence or absence of stones within the remnant, status of the common bile duct and pancreas, and any other undetected pathology that could have been responsible for the patient’s symptoms. None of these three patients had associated common bile duct calculi or any other pathology on CT scan. All the 3 patients are following up in our OPD, with resolution of symptoms and return to normal work. The biopsy report of each revealed chronic cholecystitis.

Discussion

Partial cholecystectomy (or its variations, leading to incomplete cholecystectomy) that is often performed in cases where difficulty is encountered during surgery is an important cause of persistence of symptoms after surgery, especially if not performed correctly, when (inadvertently or on purpose) simple approximation of a thin rim of tissue at the Hartmann’s pouch after removing all the stones and cauterizing the mucosa can “save the day” at the time of initial cholecystectomy. However, it can present later either as (i) a long cystic duct stump, where the stump is longer than 1 cm, or (ii) as a gallbladder remnant, which is defined as “a wider part of the free end of the remnant cystic duct, giving the impression of a diminutive gallbladder.”1 In practice, however, it is difficult to distinguish between these two conditions even on histological examination,6 though they have been implicated as a cause of post-cholecystectomy symptoms in approximately 1%–25% of patients undergoing surgery for post-cholecystectomy symptoms.[7–9] However, we could not come across any study that clearly defines the risk of recurrent symptoms in patients undergoing partial cholecystectomy, or what percentage of such patients would require re-operation.

It is not clear from the existing literature as to what is the natural history of these gallbladder remnants over a period of time, but there seems to be a trend towards surgical intervention in symptomatic patients. It could be concluded that the presence of a long cystic duct stump or a gallbladder remnant (with or without calculi) on investigation, in patients with persistent post-cholecystectomy symptoms definitely demands surgical intervention, especially when a stone is present.[1,9–12]

We could not come across any reports about the outcomes of conservative management of patients with postcholecystectomy remnant and persistent symptoms. However, the disappearance of the remnant in one of our patients who presented with jaundice, possibly because of passage of sludge from the remnant into the common bile duct does raise the remote possibility that may be, recurrent inflammation can cause gallbladder remnant fibrosis, with subsequent “completion auto-cholecystectomy” and resolution of symptoms. However, our anecdotal experience must become more “evidence-based”, maybe through some clinical trials, before being routinely prescribed to patients who present with symptoms suggestive of a gallbladder remnant.

The presentation of a gallbladder remnant can be variable not only in terms of clinical features, but also in relation to the time interval after cholecystectomy.[1,10–14] These patients can remain asymptomatic,[1,13,14] or they can present with acute symptoms (biliary colic, acute cholecystitis or acute pancreatitis) or chronic symptoms (persistent right upper quadrant discomfort or pain, food intolerance, nausea or jaundice).[1,8–14] Although there are no pathognomic symptoms, the persistence of symptoms after cholecystectomy should alert the clinician to the possibility of a gallbladder remnant, especially when coupled with radiation of pain to the shoulder, food intolerance, nausea or jaundice.[1,15] Similarly, the timing of presentation is also very variable, with patients presenting at any time between less than 1 year and upto 25 years after cholecystectomy.[16]

Ultrasound examination of the abdomen is usually the first line of investigation for patients who present with abdominal symptoms, but may not be able to pick up the remnant unless it is of a large size, or has calculi within it.[10] In such a situation, where there is a history of previous cholecystectomy along with persistence or re-appearance of symptoms, but negative findings on ultrasound, it may be prudent to use other modalities such as MRCP and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) which would show the findings of a cystic lesion in the extrahepatic biliary tree, biliary sludge, common bile duct calculi and the status of the pancreas.[1,10,11,16] ERCP is recommended only in situations where some intervention is contemplated.[1,10,16] The treatment of patients with gallbladder remnants who are symptomatic is excision of the remnant — the so-called “re-cholecystectomy”, or “completion cholecystectomy”.[1,10,11,14–17] This can be performed either laparoscopically,[1,10,11,14,17] or by open technique, and it is a good idea to have some kind of imaging prior to surgery (financial constraints coupled with the ready availability of CT scan in our hospital made the CT scan our preferred investigation). Despite our extensive experience in laparoscopic surgery, we preferred the open approach, anticipating dense adhesions and distorted anatomy in the region .The three cases that underwent ‘recholecystectomy’ ad dense intra-abdominal adhesions as well as adhesions in the Calot’s triangle, obscuring the anatomy. To conclude, although all patients with gallbladder remnants or long cystic duct stump do not develop symptoms, patients who undergo partial cholecystectomy, especially when the gallbladder flaps have been sutured together, must be counselled about the development of symptoms and followed up regularly.

References

- Pernice LM, Andreoli F. Laparoscopic treatment of stone recurrence in a gallbladder remnant: report of an additional case and literature review. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:2084–91.

- Lerner AI. Partial cholecystectomy. Can Med Assoc J. 1950;63:54–6.

- Bornman PC, Terblanche J. Subtotal cholecystectomy: for the difficult gallbladder in portal hypertension and cholecystitis. Surgery. 1985;98:1–6.

- Palanivelu C, Rajan PS, Jani K, Shetty AR, Sendhilkumar K, Senthilnathan P, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in cirrhotic patients: the role of subtotal cholecystectomy and its variants. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203:145–51.

- Ibrarullah MD, Kacker LK, Sikora SS, Saxena R, Kapoor VK, Kaushik SP. Partial cholecystectomy—safe and effective. HPB Surg. 1993;7:61–5.

- Mergener K, Clavien PA, Branch MS, Baillie J. A stone in a grossly dilated cystic duct stump: a rare cause of postcholecystectomy pain. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94:229–31.

- Moody FG. Postcholecystectomy syndromes. Surg Annu. 1987;19:205–20.

- Bodvall B, Overgaard B. Cystic duct remnant after cholecystectomy: incidence studied by cholegraphy in 500 cases, and significance in 103 reoperations. Ann Surg. 1966;163:382–90.

- Zhou PH, Liu FL, Yao LQ, Qin XY. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of post-cholecystectomy syndrome. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2003;2:117–20.

- Hussain M, Nagral S. Biliary pancreatitis secondary to stones from a gall bladder remnant. Tropical Gastroenterology. 2010;31:230–3.

- Selvaggi F, Di Bartolomeo N, De Iuliis I, Del Ciotto N, Innocenti P. Laparoscopic treated so-called reformed gallbladder in patient with postcholecystectomy chronic pain. G Chir. 2011;32:335–7.

- Rogy MA, Függer R, Herbst F, Schulz F. Reoperation after cholecystectomy. The role of the cystic duct stump. HPB Surg. 1991;4:129–35.

- Chowbey PK, Sharma A, Khullar R, Mann V, Baijal M, Vashistha A. Laparoscopic subtotal cholecystectomy: a review of 56 procedures. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2000;10:31–4.

- Tantia O, Jain M, Khanna S, Sen B. Post cholecystectomy syndrome: role of cystic duct stump and re-intervention by laparoscopic surgery. J Minim Access Surg. 2008;4:71–5.

- Whitson BA, Wolpert SI. Cholelithiasis and cholecystitis in a retained gallbladder remnant after cholecystectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205:814–15.

- Calhoun SK, Piechowiak RL. Recurrent cholecystitis and cholelithiasis in a gallbladder remnant 14 years after a converted cholecystectomy. RCR. 2010;5 DOI: 10.2484/rcr.v5i1.332.

- Chowbey PK, Bandyopadhyay SK, Sharma A, Khullar R, Soni V, Baijal M. Laparoscopic reintervention for residual gallstone disease. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2003;13:31–5.

|