48uep6bbphidvals|140

48uep6bbphidcol4|ID

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Common bile duct stones are a frequent cause of bile duct obstruction. Sometimes the calculus in the common bile duct gets impacted at the ampulla and this leads to complete biliary obstruction that may also lead to acute cholangitis.(1,2) If suppurative cholangitis occurs in this situation, then surgical removal of the stone carries high morbidity and mortality.(3) However, if the stone is impacted at the ampulla, surgical removal of the calculus may also involve carrying out surgical sphincteroplasty.(4)

Endoscopic sphincterotomy is a procedure often used for removing common bile duct stones with a high success rate and low morbidity and mortality. However, when the stone is impacted at the ampulla, it may completely block the papillary orifice and in such a situation, cannulation of the papilla may not be possible. Due to this fact, many investigators recommend precut papillotomy in patients with impacted stones at the ampulla.(2,5,6,7) However, precut sphincterotomy carries significant morbidity and mortality and the literature recommends that it should be performed by experts and endoscopists with reasonable experience.(8,9,10,11,12) In this report we report our experience of managing impacted stones at the ampulla. We tried to perform conventional biliary sphincterotomy in these patients and only if all manoeuvres failed did we resort to a needle-knife papillotomy.

Methods

Between the years 2000 and 2005, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed in 2973 patients. Of these patients 32 patients had an impacted stone at the ampulla. Of these 32 patients, eight patients had features of acute cholangitis. The plan was to attempt ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy in the conventional manner, through the normal papilla, extract the stone(s) and where needed to place a 10 Fr plastic biliary endoprosthesis. Only if this approach failed would a precut needle be used to incise the papilla and deliver the stone(s). The success or failure of the procedure was recorded and the complications noted.

The presenting symptoms of the patients were pain in 24 and fever in eight. Jaundice was noted in all patients. All patients were managed initially with intravenous fluids, electrolytes and antibiotics. If coagulopathy was present, it was corrected with intravenous administration of fresh frozen plasma. Vitamin K injections were administered to all patients.

ERCP was performed in the prone position in young patients who were haemodynamically stable and in the left lateral position in elderly patients with/without comorbidities. Conscious intravenous sedation was administered to all but two patients. These two patients were aged, haemodynamically unstable and had other comorbid conditions, therefore, ERCP had to be performed in these patients without any intravenous sedation. Duodenal aperistalsis was achieved with intravenous injection of hyoscine butyl bromide (Buscopan, German Remedies, Mumbai).

Results

The mean (standard deviation) age of the patients was 39.4 (14.6) years. There were 22 female and 10 male patients. At ERCP, the papilla was bulging and oedematous in all patients. A small biliary fistula was noted above the impacted stone in one of the patients. However, ulceration or necrosis of the papilla was not observed in any of the patients.

In 14 patients there was a single calculus impacted at the ampulla. In others two or more calculi were noted in the biliary tree. The gallbladder was in situ in 24 patients while the other eight had undergone cholecystectomy in the past. Of the 24 patients with gallbladder in situ, gallstones were present in 21 patients. In three patients, although the gallbladder was intact, no calculus was present in the gallbladder.

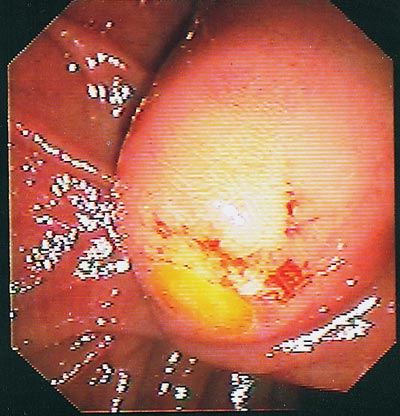

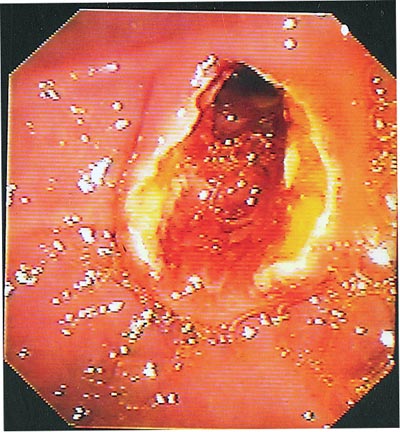

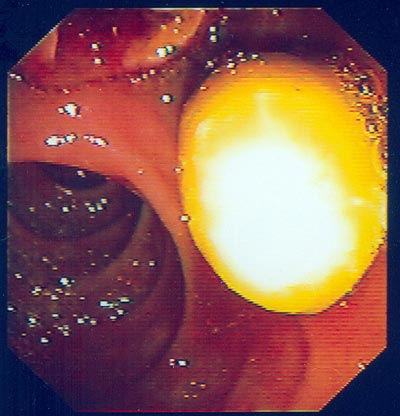

Of the 32 patients with impacted calculus at the ampulla, ERCP with wire-guided endoscopic sphincterotomy could be performed through the normal papillary orifice in 23 after the impacted stone was dislodged. It was possible to remove the impacted calculus in all 23 patients. In 14 patients it could be performed easily while in the other nine some difficulty was encountered and the long-route had to be employed in seven patients. Pressure, by the sphincterotome, at the ampulla failed to dislodge the impacted stone in four patients. However, pressure by the side of the papillary orifice on the ampulla could dislodge the impacted calculus and cannulation through the papillary orifice could be performed. Guide-wire cannulation of the papilla was required in four patients. One patient was 3 months pregnant and presented with acute cholangitis due to impacted solitary bile duct calculus (Figure 1). In this patient cannulation of the bile duct was performed and the position of sphicterotome in the bile duct was confirmed by aspiration of bile (Figure 2). Sphincterotomy by the conventional method was easily performed (Figure 3) and a large stone delivered immediately and spontaneously (Figure 4).

In nine patients the papillary opening could not be cannulated and we decided to perform a precut sphincterotomy using a needle knife. An incision was given a few millimeters above the papillary orifice and the length and depth was gradually extended by repeatedly cutting over the impacted stone. Finally the incision was extended to the papilla too. With the use of needle knife precut papillotomy, stones impacted at the ampulla could be extracted in all the nine patients in whom it was employed. In one patient another large stone was also present in the bile duct that could not be removed. Post precut incision and removal of the impacted stone, bleeding from the papillotomy site occurred. Diluted 1:10 000 adrenaline was injected at the apex of the incision and haemostasis achieved. A 10 Fr biliary endoprosthesis was placed in the bile duct. A week later the endoprosthesis was removed and the stone was fragmented using mechanical lithotripsy (Olympus BML 3Q) and the fragments extracted.

All patients with acute cholangitis had dramatic recovery after removal of the impacted stone at the ampulla. Other patients were also relieved of their symptoms.No complication was noted in any patient in whom conventional sphincterotomy was performed. When needle knife sphincterotomy was done (n = 9), three patients suffered a bleed requiring injection of 1:10,0000 adrenaline. None of the patients developed pancreatitis or perforation.

Fig. 1. A common bile duct stone is seen impacted at the ampulla. The patient was

also pregnant

Fig. 2. Sphincterotome advanced in the bile duct after aspiration of bile (to confirm

the position of the sphincterotome in the bile duct)

Fig. 3. Endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed using the conventional method.

Fig. 4. A large calculus impacted at the ampulla popped out after endoscopic

sphincterotomy.

Discussion

Gall stone impaction of the common bile duct at the ampulla of Vater is not uncommon.(2) Most patients experience severe pain and many of them develop complete obstruction to the flow of bile resulting in acute cholangitis.(1,2) This was noted in eight patients in this series. With an impacted stone at the ampulla even surgical procedures become difficult. Surgical sphincteroplasty is required in most patients,(4) although cholecystectomy with open duct exploration (leaving the sphincter of Oddi intact) has also been reported as very successful.(13) For such an approach, the gall bladder should be in situ. In the present study, all patients with acute cholangitis had dramatic recovery following removal of the impacted calculus at the ampulla.

Several studies have noted the excellent results of needle knife precut papillotomy in patients with impacted bile duct calculi at the ampulla.(2,4,5,6) However, needle knife papillotomy is a risky procedure with a reported complication rate of 22 %.(11) Moreover, it is the domain of the experienced endoscopist.(7,8,9,10,11,12,13) It should also be noted that ampullary impaction of gallstones with or without cholangitis is a special situation. In patients with impacted calculus, there is hyperaemia and oedema of the ampulla followed by increased risk of bleeding, after precut papillotomy. Bleeding was observed in three patients in this study. Similar results have been reported earlier.(2)

One patient was pregnant and we had to perform endoscopic sphincterotomy without fluoroscopy. Aspiration of bile indicated that the bile duct had been cannulated and endoscopic sphincterotomy was performed using the conventional method. Past experience in ERCP enabled us to perform this procedure efficiently and without hesitation.(14,15,16) We had used this technique in 13 pregnant patients before this one with good results (unpublished observations). Other authors also report similar success in performing therapeutic ERCP procedures in pregnant women(17,18,19,20) and for placement of endoscopic nasobiliary catheters in patients with acute cholangitis.(21,22)

A study from Hong-Kong demonstrated that cannulation of the papilla by the normal route is difficult in the majority of patients with impacted stones at the ampulla. The authors resorted to needle knife papillotomy instead.(2) Complications encountered in the study included mild bleeding in four patients; this was controlled by endoscopic injection of dilute adrenaline solution. As in the present study, pancreatitis, perforation or exacerbation of cholangitis was not observed.(2)

The results of our study do not agree with those from a study by Leung et al.(2) We were successful in cannulating the papilla by the normal ERCP route in a majority of patients, although we encountered some difficulty in nine patients. The long route was required to visualise the papillary orifice in seven patients. The situation is very similar to that observed in patients with periampullary tumours, where the papillary orifice is displaced distally towards the duodenal mucosa. In nine patients the impacted calculus could not be dislodged. The chance of dislodgement depends on how tightly the stone is impacted at the ampulla and on the perseverance of the endoscopist.

Precut papillotomy was resorted to in nine patients in this series and although the complications encountered in the series are not very significant, we recommend the use of endoscopic sphincterotomy through the conventional route for impacted stones at the ampulla. Needle knife papillotomy may be utilised when cannulation of the papilla is impossible by the conventional route. The advantage of the conventional route is that it is wire-guided and therefore a more stable and controlled sphincterotomy incision can be made as opposed to a needle knife papillotomy that is freehand and unstable. Moreover, most endoscopists are familiar with the conventional endoscopic sphincterotomy but may not be adept at performing needle knife papillotomy.

References

1. Leung JW, Chung SC, Sung JJ, Banez VP, Li AK. Urgent endoscopic drainage for acute suppurative cholangitis. Lancet. 1989;1:1307–9.

2. Leung JW, Banez VP, Chung SC. Precut (needle knife) papillotomy for impacted common bile duct stone at the ampulla. Am J Gastroenterol. 1990;85:991–3.

3. Boey JH, Way LW. Acute cholangitis. Ann Surg. 1980;191:264–70.

4. Rutledge RH. Sphincteroplasty and choledochoduodenostomy for benign biliary obstructions. Ann Surg. 1976;183:476–87.

5. Guitron A, Adalid R, Nares J, Albores Manzo A. Precut sphincterotomy for impacted choledocholithiasis at the Vater’s ampulla. Rev Gastroenterol Mex (in Spanish). 1996;61:338–41.

6. Larkin CJ, Huibregtse K. Precut sphincterotomy: indications, pitfalls, and complications. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2001;3:147–53.

7. Sriram PV, Rao GV, Reddy DN. The precut-when, where and how? A review. Endoscopy. 2003;35:S24-30

8. Cotton PB. Precut sphincterotomy: a risky technique for experts only. Gastrointest Endosc. 1989;35:578–579

9. Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, et al. Complications of endoscopic biliary sphincterotomy. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:909–18.

10. Bolzan HE, Spatola J, González J, Luna R, García G. Precut Vater’s papilla. Prospective evaluation of frequency of use, effectiveness, complication and mortality. Cooperative study in the northwest of the province of Buenos Aires. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 2001;31:323–7.

11. de la Morena EJ, Dominguez M, Lumbreras M, Opio V, Moyano E, Garæia Alvarez J. Self-training in needle-knife sphincterotomy. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;23:109–15.

12. Harewood GC, Baron TH. An assessment of the learning curve forprecut biliary sphincterotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:1708–12.

13. Thompson JE Jr, Bennion RS. The surgical management of impacted common bile duct stones without sphincter ablation. Arch Surg.1989;124:1216–9.

14. Misra SP, Gupta A, Agarwal SK. Endoscopic sphincterotomy, nasobiliary drainage and biliary stent placement without image intensification. Br J Surg. 1992;79:1179–80.

15. Misra SP, Dwivedi M. Biliary endoprosthesis as an alternative to endoscopic nasobiliary drainage in patients with acute cholangitis. Endoscopy. 1996;28:746–9.

16. Misra SP, Dwivedi M. Should therapeutic ERCP be conducted without fluoroscopy in special circumstances? Endoscopy. 1998;30:306–7.

17. Llach J, Bordas JM, Gines A, Mondelo F, Terés J. Endoscopic sphincterotomy in pregnancy. Endoscopy. 1997;29:52–3.

18. Simmons DC, Tarnasky PR, Rivera-Alsina ME, Lopez JF, Edman CD. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopanctreatography (ERCP) in pregnancy without the use of radiation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1467–9.

19. Savas MC, Kadayifci A, Koruk M. Re: Tham et al.Safety of ERCP during pregnancy . Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2331–2.

20. Gupta R, Tandan M, Lakhtakia S, Santosh D, Rao GV, Reddy DN. Safety of therapeutic ERCP in pregnancy-an Indian experience. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2005;24:161-3.

21. Chawla YK, Sharma BC, Singh R, Sharma TR, Dilawari JB. Emergency endoscopic nasobiliary drainage without the aid of fluoroscopy. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1993;12:97–8.

22. Wang HP, Huang SP, Sun MS, Chen JH, Wang HH, Lin CC. Urgent endoscopic nasobiliary drainage without fluoroscopic guidance: A useful treatment for critically ill patients with biliary obstruction. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:741–4.