48uep6bbphidcol2|ID

48uep6bbphidvals|3027

48uep6bbph|2000F98CTab_Articles|Fulltext

Introduction

Amoebic infections continue to plague the underprivileged population all over the world. Amoebic liver abscess (ALA) is a form of amoebic infection which continues to occur despite rampant unsolicited/over-the-counter antibiotic use in India especially for gastrointestinal (GI) problems.1,2 Though non-potable drinking water or unhygienic food (by faecal-oral transmission) is the cause of amebic gut infections, the exact environment in which liver abscess develops is not well understood; concomitant GI infection is found in 53%-77% of cases.3-6 Though amebic serology by different methods (immune-hemagglutination, ELISA, immunofluorescent assay) which employ different cut off titres for positivity are used for diagnosis, this necessarily generates indeterminate cases with lower antibody titres whose behaviour is like ALA as regards response to therapy and course.7 Also the factors influencing seropositivity are not known. Though bigger abscesses are drained, small-sized abscesses tend to be treated conservatively with oral or intravenous (IV) antibiotics7,8 aiming at symptom resolution only but their long term outcome is unclear. Regular alcohol (especially indigenously brewed ones like toddy) consumption is almost universal among ALA patients in the subcontinent5,6 and this might have bearing on the clinical outcome. To throw further light on these understudied aspects, we studied the sociodemographic and clinical features of such patients over 10 years and also followed them up for their long term treatment outcome.

Methods

Study population

This is a prospective data analysis of 163 consecutive patients of ALA attending the outpatient and inpatient department of this hospital from January 2009 to December 2018. Diagnosis:Liver abscess was diagnosed based on clinical presentation (fever, right upper quadrant abdominal pain, tender hepatomegaly) and abdominal ultrasonography (USG, with/without computerised tomography scan as per need) finding of well defined non-homogeneous, hypoechoic, round or oval lesion/s wherein their site, size, number and involvement of liver capsule, vascular and biliary structures were noted as also any feature of chronic liver disease. All patients underwent clinical, radiological, routine stool, serological (antiamebic IgG antibody by ELISA) and colonoscopic examination and amoebic aetiology were determined by various combinations of past or incident history of diarrhoea/dysentery, positive stool examination for amoeba (cysts or trophozoites), radiological appearance of the lesion, aspirated pus study (“anchovy sauce” appearance with/without demonstrable amoeba), antiamebic antibody in titre > 1:160 (labelled as seropositive with any lower titre labelled as seronegative), colonoscopy findings andresponse to therapy (especially in seronegative cases). The pus was also sent for culture to rule out other infections andtargeted biopsies of the colonoscopic lesion (if present) were sent for histopathological examination. Other tests performed were complete hemogram, liver function test (LFT), coagulation profile, serologies (HBsAg, AntiHCV and echinococcosis), serum alpha-fetoprotein and others as indicated.Sociodemographic features of patients studied included education, family income (socioeconomic status), eating/personal hygiene and alcohol consumption including type, amount, frequency and place of drinking. Treatment and follow up:All patients were treated by complete USG-guided needle aspiration of the liquefied contents of the abscess cavity with a long 18 gauge needle irrespective of its size in a single sitting after admission followed by IV metronidazole 500 mg thrice daily for 7-10 days along with injection ceftriaxone 1 g twice daily for first 5 days. This was done after correction of coagulation abnormalities if any. Those with complaints of diarrhoea/dysentery or colonic lesion on colonoscopy were also given diloxanide furoate 500 mg thrice daily for 10 days. They were then followed up 3 monthly for 1 year with LFT (in those deranged) and USG of the abdomen and thereafter yearly. They were also free to report anytime if they felt so if there was a recurrence of symptoms and if abdominal USG was done for any other reason. All alcohol consumers were asked to abstain from alcohol consumption in future. The study protocol was cleared by the institutional ethics committee and written consent was obtained from all patients to be included in the study.

Statistics

Continuous and discrete variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and percentage respectively and compared by student’s t-test and chi-square test respectively. A two-sided p <0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Clinical presentation

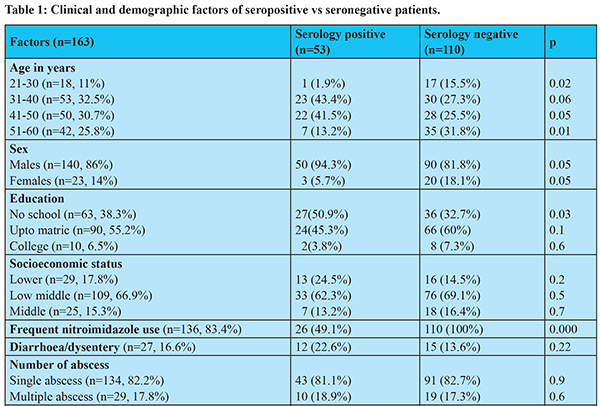

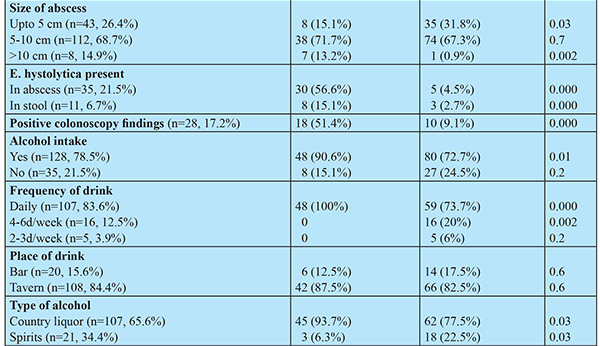

109 (63.9%) abscesses were treated in the first 5 years compared to 54 (36.1%) in the last 5 years. The mean age was 45.8 (+ 12.4, 24-58) years. History of diarrhoea was present in 27 (16.6%) and dysentery in 5 (3.1%) but none at presentation. Pain abdomen (right upper quadrant) with intercostal tenderness and fever occurred in 114 (69.9%) but 32 (19.6%) had fever with chills alone. 100% had tender hepatomegaly. Other results are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. There was frequent nitroimidazole intake in 83.4% of patients for recurrent and even minor GI problems.

Radiology

Among those with multiple abscesses 25 had two and 4 (2.5%) had three abscesses, the rest had a single abscess of mean diameter 8.4 (4-15) cm. The location was right lobe in 158 (97%) and left lobe in 5 (3%) patients. None had evidence of chronic liver disease or complicated abscess. Insignificant pleural effusion was present in 10 (6.5%) but none had ascites.

Laboratory results

The pus was pinkish-brown “anchovy sauce” type in all but E. histolytica was demonstrated in 35 (21.5%) and culture yielded E.coli in 14 (8.6%). The volume of pus drained was 20-350 ml. Amebic serology was positive in 53 (32.5%) patients. Of the seronegative ones, 45(41%) had titre 1:40, 40(36.4% ) had titre 1:20 and 25(22.6%) had titre 1:10 or less. On colonoscopy, there was right colonic ulcers in 21 (12.9%) and cecal mass in 7 (4.3%). Diabetes mellitus was present in 25 (15.3%), biochemical jaundice in 45 (27.6%) but mild clinical jaundice in only 12 (7.4%) patients.

Treatment outcome and follow up: All patients had prompt symptom relief with the above treatment especially pain and fever. LFT normalised in all within 1-2 months. Abscess cavity gradually decreased in all and disappeared by 8-9 months in those with a single smaller cavity. The resolution took 1 year or more in those with larger or multiple abscess cavities. 24 (14.7%) patients were lost to follow up after 1 year. Mean follow up in the rest was 5.8 (± 2.6, 4-10) years and there was no recurrence till last follow up in all cases.

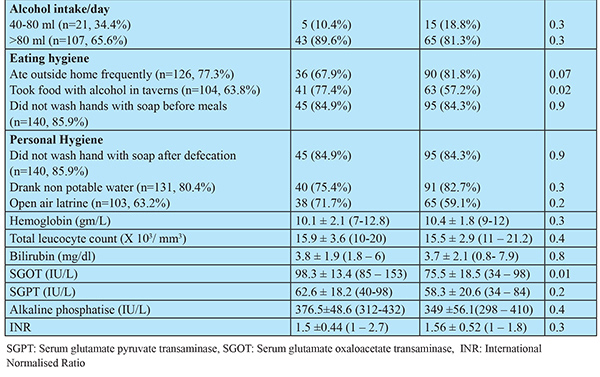

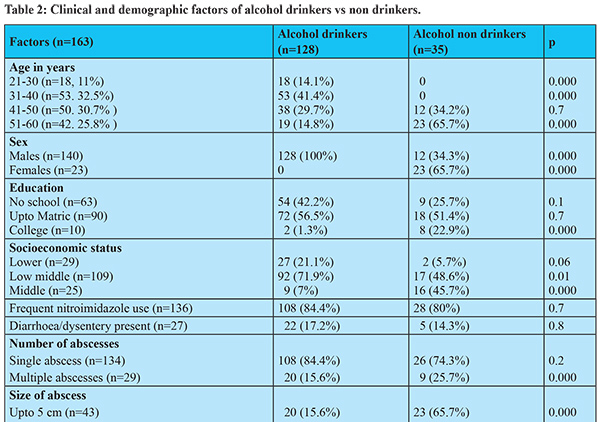

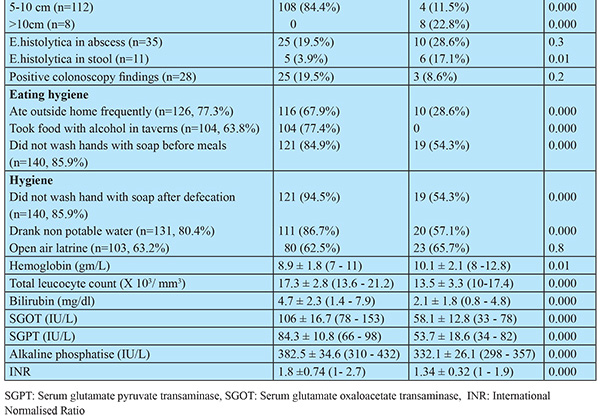

Sociodemographic factors:138 (84.7%) belonged to the low and lower middle class, 137 (84%) hailed from rural/suburban areas and 124 (76.1%) had education less than matric. Personal and eating hygiene was poorer among alcoholics and > 85% of patients drank > 80 ml of indigenously brewed alcohol/ beverageon daily basis in unhygienic taverns (Table 2). Serology was significantly higher in drinkers [>85% of positive serology was in < 50 year age group (Table 1) commensurate with the >85% alcohol drinkers in this age group though their use of nitroimidazoles was similar to non-alcoholics (Table 2)]. As shown in Table 1, it was also related to the daily drinking of indigenously brewed liquorin unhygienic taverns but not to its quantity. It was unrelated to personal and eating hygiene except taking food with alcohol in taverns [though alcoholics had poorer eating and personal hygiene (Table 2)]. It was unrelated to the socioeconomic status. However, this was more in people who have not gone to school at all but this was unrelated to alcoholism (Table 2). It was also related to having an abscess of size > 10 cm, positive amoeba in pus and stool and positive colonoscopy findings (but these factors were not influenced by alcohol intake) but not to the number of abscesses or the presence of incident or past diarrhoea/ dysentery (Table 1).

Discussion

This study shows that the incidence of ALA is decreasing lately possibly due to improving hygienic standards. The clinical findings are commensurate with other studies like higher occurrence in males, low frequency of previous or incident diarrhoea/dysentery, low positivity of E. histolytica in pus and stool, the high number of alcoholic patients and blood parameters.3,5,6,9 Jaundice occurred in 35% of our patients which is higher than previously reported 5-20%6,8,9 but in most, it was biochemicaland not evident clinically. The higher incidence of jaundice is due to the high number of alcohol drinkers who had significantly higher bilirubin, serum glutamate oxaloacetate transaminase (SGOT), serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase (SGPT with SGOT > SGPT), alkaline phosphatase and international normalised ratio level (Table 2) suggesting an element of alcoholic hepatitis which is expected as all were actively drinking near the time of reporting. Jaundice was not correlated to the size, number or location of the abscess.

Though intestinal amoebiasis is common among women and children, liver abscesses are distinctly uncommon. These differences have been linked to multiple mechanisms like (a) predisposition caused by testosterone by immunologic alteration, (b) more alcohol consumption in males, (c) iron overload in the liver caused by the high iron content of indigenously brewed alcohol beverage, (d) menstrual blood (and so iron) loss in females.10,11

Amebic serology was positive (titre > 1:160) in about one-third of patients though it was also present in much lower titre in others (seronegative group). There is rampant use of nitroimidazoles for even minor GI disturbance in the study region which might decrease the parasite load and prevent the development of antibodies and our study demonstrated that those taking such nitroimidazoles had a lower occurrence of antibodies. This might also be the reason for lower concomitant positive colonoscopy findings3-5 along with low occurrence of diarrhoea at presentation. It is reported that such indeterminate/atypical cases with lower antibody titre behave like ALA as regards response to therapy and outcome even though the antibody titre fails to rise in subsequent tests.7 Also 10% of cases of acute ALA may be seronegative and in such atypical cases, response to antiamebic therapy is taken as proof of amebic aetiology as done in our study.12 Reasons quoted for such occurrence are (a) cut off value for a positive test may be variable especially in endemic areas like ours, (b) lower immunity, (c) time lag of at least 7 days for antibody development. Alcohol consumption is common in patients of ALA5,6,9,13 but the fact that it does not occur in those with chronic liver disease (as is also demonstrated in the present study) is an enigma and various reasons have been put forward.13 Our study had important sociodemographic findings related to alcohol use and the development of antibodies. Positive serology was significantly higher among alcoholics who drank indigenously brewed alcoholic beverages on a daily basis in unhygienic conditions but was not related to alcohol quantity. Though personal and eating hygiene was poorer among alcoholics, the only factor which influenced antibody formation was taking food along with alcohol in unhygienic taverns even though their intake of nitroimidazoles was similar to non-alcoholics. This shows that alcohol independently influences antibody formation and this may again be related to higher parasite dose (hygiene becomes poorer in the inebriated state with unhygienic food acting as a surrogate). Yet alcoholics had lower positivity for stool amoeba. This might be due to alcohol increasing the gut permeability and the invasive virulence of ameba14 but at the same time restricting their proliferation inside the gut due to gut dysbiosis.10 A much lower occurrence of stool amoeba even in presence of a high isolation rate from abscess pus has also been reported.15 Occurrence of antibody was also found in those with bigger abscess (>10 cm) with the demonstrable amoeba in pus and stool and those with positive colonoscopic findings and all these factors are possibly related to higher parasite load though alcohol addiction did not influence them. The finding of higher antibodies in those who have not gone to school at all (though this was not related to alcoholism) possibly reflects poor hygiene awareness.

This study showed that early intervention by fine-needle pus aspiration under appropriate antibiotic cover gave quick and lasting relief without any complication or recurrence in long term. Unfortunately, there is a lack of consensus among the medical community regarding the need for intervention in such cases and various guidelines have been put forth regarding indications of intervention.5,7,8 Most prefer oral or IVdrug therapy of varying duration first (especially for small-sized abscess) but such studies have short followed up and are silent on the long term outcome of those who respond. In the author’s experience, IV metronidazole for 3-5 days do not give adequate symptomatic relief in most cases and there is a chance of relapse in those who do without complete resolution. Moreover, the duration of drug therapy is uncertain whereas complete aspiration at first instance gives quick and lasting relief and avoid the perils of prolonged antibiotic use. Though a metanalysis16 (consisting of ten low-quality trials) did not find a significant benefit of drug therapy in combination with aspiration vs drug therapy alone, a very recent study9 treating patients initially by metronidazole for 3 days gave symptomatic relief in only 46% and finally 76% needed aspiration. A combination of aspiration and drug therapy has also been recommended by other authors12

as it decreases overall patient suffering which should be the aim of any therapeutic modality.

Our study also had certain limitations.

(1) The serology was positive in one-third of patients and definite amebic aetiology in seronegative cases could have been further confirmed by PCR of aspirated pus for ameba15 or serum antigen testing but these facilities were not available. Yet the nature of pus (“anchovy sauce” appearance, demonstrable amoeba in some, culture negativity for polymicrobial infection), other clinical features and response to antiamebic therapy in such cases is a pointer to amebic aetiology.12 (2) 24 (14.7%) patients were lost to follow up after 1 year. All had a small-sized abscess and chances of recurrence were very unlikely.

Conclusion

A combination of pus aspiration and drug therapy irrespective of abscess isze was effective in our retrospective cohort analysis and this combination treatment modality should be further evaluated with a randomized controlled trial. The association of alcohol and ALA is complex and multifactorial14 and alcohol also influences seropositivity but more epidemiologic data is needed on these aspects. The titre of serology needed for diagnosis of ALA needs to be revisited in India.

References

- Porter G, Grills N. Medication misuse in India: a major public health issue in India. Journal of Public Health 2016;38 (2): e150–e157.

- Farooqui HH, Selvaraj S, Mehta A et al.Community level antibiotic utilization in India and its comparison vis-à-vis European countries: Evidence from pharmaceutical sales data. Plos One 2018;13(10):e0204805.

- Misra SP, Misra V, Dwivedi M et al. Factors influencing colonic involvement in patients with amebic liver abscess. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 59:512–516.

- Sachdev GK, Dhol P. Colonic involvement in patients with amebic liver abscess: endoscopic findings. Gastrointest Endosc 1997; 46:37–39.

- Dudha S, Premkumar M, Devurgowda D et al. Clinical and Endoscopic Management of Synchronous Amoebic Liver Abscess and Bleeding Colonic Ulcers. J Assoc of Physicians India 2019; 67:14-18.

- Goswami A, Dadhich S, and Bhargava N. Colonic involvement in amebic liver abscess: does site matter? Ann Gastroenterol. 2014; 27(2): 156–16.

- Khan R, Hamid S, Abid S et al. Predictive factors for early aspiration in liver abscess. World J Gastroenterol. 2008 ;14(13):2089-93.

- Kale S, Nanavati AJ, Borle N et al. Outcomes of a conservative approach to management in amoebic liver abscess. J Postgrad Med 2017; 63:16-20.

- Jha SK, Kumar U, Dayal VM et al. Efficacy of Nitazoxanide is Inferior to Metronidazole in Patients with Uncomplicated Amebic Liver Abscess: A Prospective Randomized Control Trial.Tropical Gastroenterology 2018;39(1):10-16

- Kumanan T, Sujanitha V, Balakumar S et al. Amoebic Liver Abscess and Indigenous Alcoholic Beverages in the Tropics. J Trop Med. 2018, Article ID 6901751.

- Tharmaratnam T, Kumanan T, Iskandar MA et al. Entamoeba histolytica and amoebic liver abscess in northern Sri Lanka: a public health problem. Tropical Medicine and Health 2020; 48. Epub ahead of print

- Singh R, Adhikari DR, Patil BP et al. Amoebic Liver Abscess: An Appraisal. Int Surg: 2011; 6 (4): 305-309.

- Kannathasan S, Murugananthan A, Kumanan T et al. Epidemiology and factors associated with an amoebic liver abscess in northern Sri Lanka. BMC Public Health 2018; 18:118.

- Kumar R, Jha AK. Association between local alcoholic beverages and amoebic liver abscess in the Indian subcontinent: Weird but true!JGH Open. 2019; 3(3): 266–267.

- Singh A, Banerjee T, Kumar R et al. Prevalence of cases of amebic liver abscess in a tertiary care centre in India: A study on risk factors, associated microflora and strain variation of Entamoeba histolytica. PLoS One. 2019;14(4):e0214880.

- Chavez-Tapia NC, Hernandez-Calleros J et al. Image-guided percutaneous procedure plus metronidazole versus metronidazole alone for uncomplicated amoebic liver abscess. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009 Jan 21;(1):CD004886.